[This is taken from Claud Field's Mystics and Saints of Islam, originally published in 1910.]

Jalaluddin Rumi has been called by Professor Ethé (in the Encyclopædia Britannica) "the greatest pantheistic writer of all ages." However that may be, he is certainly the greatest mystical poet of Persia, though not so well known in Europe as Saadi, Hafiz and Omar Khayyam. Saadi, Jalaluddin's contemporary, seems to have been conscious of this, for when asked by the Prince of Shiraz to send him the finest poem which had been published in Persia, he sent an ode from Jalaluddin's "Diwan."

Jalaluddin ("the glory of religion") was born at Balkh, in Central Asia (1207 AD), where his father, Behauddin, was a professor of theology under the Sultan Khwarezm Shah. His discourses were largely attended by great and small, but for some reason he seems to have excited the Sultan's displeasure. He therefore left Balkh with the whole of his family and dependants, taking an oath not to return thither while the Sultan was on the throne. Behauddin's way led him to Nishapur, where he met the Sheikh Fariddudin Attar, who, pointing to Jalaluddin, said, "Take care! This son of yours will light a great flame in the world." Attar also presented the boy with his Asrarnama, or "book of secrets." In every town which they visited the chief men came to see Behauddin and listened to his teaching. Behauddin and his son made the pilgrimage to Mecca, after which the former settled at Konia (Iconium), in Asia Minor ("Roum"), whence the poet received the title "Rumi." Here Behauddin obtained as great a reputation as he had done at Balkh, and on his death Jalaluddin succeeded him as "Sheikh," or spiritual instructor. He soon grew tired of the ordinary round of Mohammedan learning and gave himself up to mysticism. This tendency of his received an additional impulse from the arrival in Iconium of an extraordinary man, the fakir Shams-i-Tabriz, a disciple of the celebrated Sheikh Ruknuddin.

One day Ruknuddin, when conversing with Shams-i-Tabriz, had said to him, "In the land of Roum is a Sufi who glows with divine love; thou must go thither and fan this glow to a clear flame." Shams-i-Tabriz immediately went to Iconium. On his arrival he met Jalaluddin riding on a mule in the midst of a throng of disciples who were escorting him from the lecture hall to his house. He at once intuitively recognised that here was the object of his search and his longing. He therefore went straight up to him and asked, "What is the aim of all the teaching that you give, and all the religious exercises which you practise?" "The aim of my teaching," answered Jalaluddin, "is the regulation of conduct as prescribed by the traditions and the moral and religious law." "All this," answered Shams-i-Tabriz, "is mere skimming the surface." "But what then is under the surface?" asked Jalaluddin. "Only complete union of the knower with the known is knowledge," answered Shams-i-Tabriz and quoted the following verse of Hakim Sanai:—

Only when knowledge frees thee from thyself,

Is such knowledge better than ignorance.

These words made a most powerful impression on Jalaluddin, so that he plied Shams-i-Tabriz with questions and resorted with him to lonely desert places for uninterrupted converse. This led to a neglect of teaching on his part, and his pupils and adherents persecuted and ridiculed Shams-i-Tabriz, calling him "a bare-footed and bare-headed fakir, who has come hither to lead the pattern of believers astray." Their treatment caused Shams-i-Tabriz to flee to his native city without telling Jalaluddin. The latter, however, overcome by love and longing, went after him, found him and persuaded him to return.

Shams-i-Tabriz did so, and for some time longer they lived in friendly intercourse together; but Jalaluddin's disciples again began to persecute the former, who departed to Syria, where he remained two years. During this interval, in order to soften the pain of separation, Jalaluddin instituted mystical dances, which he ordered to be accompanied by the flute. This was the beginning of the celebrated order of Mevlevis, or dancing dervishes, which has now existed for over six hundred years, successively presided over by descendants of Jalaluddin. Their gyrations are intended to symbolise the wheelings of the planets round their central sun and the attraction of the creature to the Creator. They exist in large numbers in Turkey, and to this day the coronation of the Sultan of Turkey is not considered complete till he is girded with a sword by the head dervish of the Mevlevi order.

Shams-i-Tabriz subsequently returned to Konia and perished there in a tumult, the details of which are not known. To commemorate his friend Jalaluddin composed his "Diwan-i-Shams-i-Tabriz," putting the latter's name in place of his own as the author. It is a collection of spirited odes setting forth the doctrines of Sufistic Pantheism. The following lines on pilgrimage to the Kaaba afford a good instance of the way in which the Sufi poets endeavour to spiritualise the rites of Islam:—

Beats there a heart within that breast of thine,

Then compass reverently its sacred shrine:

For the essential Kaaba is the heart,

And no proud pile of perishable art.

When God ordained the pilgrim rite, that sign

Was meant to lead thy thoughts to things divine;

A thousand times he treads that round in vain

Who gives one human heart a needless pain.

Leave wealth behind; bring God thy heart, Whose light

Will guide thy footsteps through the gloomiest night.

God spurns the riches of a thousand coffers,

And says, 'The saint is he his heart who offers;

Nor gold nor silver seek I, but above

All gifts the heart, and buy it with My love:

Yea! one sad, contrite heart which men despise

More than My throne and fixed decree I prize';

The meanest heart that ever man has spurned

Is a clear glass where God may be discerned.

The following ode, translated by the late Professor Falconer, is frankly pantheistic:—

I was, ere a name had been named upon earth,

Ere one trace yet existed of aught that has birth:

When the locks of the Loved One streamed forth for a sign

And Being was none, save the Presence Divine.

Named and name were alike emanations from Me,

Ere aught that was 'I' yet existed, or 'We';

Ere the veil of the flesh for Messiah was wrought,

To the Godhead I bowed in prostration of thought;

I measured intently, I pondered with heed

(But, ah, fruitless my labour!) the Cross and its Creed:

To the pagod I rushed and the Magian's shrine,

But my eye caught no glimpse of a glory divine;

The reins of research to the Kaaba I bent,

Whither hopefully thronging the old and young went;

Candahàr and Herat searched I wistfully through,

Nor above nor beneath came the Loved One to view.

I toiled to the summit, wild, pathless and lone,

Of the globe-girding Kàf, but the Anka had flown!

The seventh earth I traversed, the seventh heaven explored,

But in neither discerned I the court of the Lord.

I questioned the Pen and the Tablet of Fate,

But they whispered not where He pavilions His state;

My vision I strained, but my God-scanning eye

No trace that to Godhead belongs could descry.

My glance I bent inward: within my own breast

Lo, the vainly sought elsewhere! the Godhead confessed!

Jalaluddin's chief work, the Masnavi, containing upwards of 26,000 couplets, was undertaken at the instance of one of his disciples and intimates, Husam-ud-din, who had often urged him to put his teaching into a written form. One day when Husam-ud-din pressed the subject upon him, Jalaluddin drew from his turban a paper containing the opening couplets of the Masnavi, which are thus translated by Mr. Whinfield:—

Hearken to the reed flute, how it discourses,

When complaining of the pains of separation:—

'Ever since they tore me from my ozier-bed,

My plaintive notes have moved men and women to tears.

I burst my breast, striving to give vent to sighs,

And to express the pangs of my yearning for my home.

He who abides far away from his homeIs ever longing for the day he shall return;

My wailing is heard in every throng,In concert with them that rejoice and them that weep.'

The reed flute is one of the principal instruments in the melancholy music which accompanies the dancing of the Mevlevi dervishes. It is a picture of the Sufi or enlightened man, whose life is, or ought to be, one long lament over his separation from the Godhead, for which he yearns till his purified spirit is re-absorbed into the Supreme Unity. We are here reminded of the words of Novalis, "Philosophy is, properly speaking, home sickness; the wish to be everywhere at home."

Briefly speaking, the subject of the Masnavi may be said to be the love of the soul for God as its Origin, to Whom it longs to return, not the submission of the ordinary pious Moslem to the iron despotism of Allah. This thesis is illustrated with an extraordinary wealth of imagery and apologue throughout the six books composing the work. The following fable illustrates the familiar Sufi doctrine that all religions are the same to God, Who only regards the heart:—

Moses, to his horror, heard one summer day

A benighted shepherd blasphemously pray:

'Lord!' he said, 'I would I knew Thee, where Thou art,

That for Thee I might perform a servant's part;

Comb Thy hair and dust Thy shoes and sweep Thy room,

Bring Thee every morning milk and honeycomb.

'Moses cried: 'Blasphemer! curb thy blatant speech!

Whom art thou addressing? Lord of all and each,

Allah the Almighty? Thinkest thou He doth need

Thine officious folly? Wilt all bounds exceed?

Miscreant, have a care, lest thunderbolts should break

On our heads and others perish for thy sake.

Without eyes He seeth, without ears He hears,

Hath no son nor partner through the endless years,

Space cannot contain Him, time He is above,

All the limits that He knows are Light and Love.'

Put to shame, the shepherd, his poor garment rent,

Went away disheartened, all his ardour spent.

Then spake God to Moses: 'Why hast thou from Me

Driven away My servant, who goes heavily?

Not for severance it was, but union,

I commissioned thee to preach, O hasty one!

Hatefullest of all things is to Me divorce,

And the worst of all ways is the way of force.

I made not creation, Self to aggrandize,

But that creatures might with Me communion prize.

What though childish tongues trip? 'Tis the heart I see,

If it really loves Me in sincerity.

Blood-stains of the martyrs no ablution need,

Some mistakes are better than a cautious creed,

Once within the Kaaba, wheresoe'er men turn,

Is it much to Him Who spirits doth discern?

Love's religion comprehends each creed and sect,

Love flies straight to God, and outsoars intellect.

If the gem be real, what matters the device?

Love in seas of sorrow finds the pearl of price.'

A similar lesson is taught by the apologue of the "Elephant in the Dark":—

During the reign of an Eastern sovereign, he remarked that the learned men of his time differed widely in their estimate of the Deity, each ascribing to Him different characteristics. So he had an elephant brought in secret to his capital and placed in a dark chamber; then, inviting those learned men, he told them that he was in possession of an animal which none of them had ever seen. He requested them to accompany him to the chamber, and, on entering it, said that the animal was before them, and asked if they could see it. Being answered in the negative, he begged them to approach and feel it, which they did, each touching it in a different part. After returning to the light, he asked them what they thought the animal was really like. One declared that it was a huge column, another that it was a rough hide, a third that it was of ivory, a fourth that it had huge flaps of some coarse substance; but not one could correctly state what the animal was. They returned to the chamber, and when the light was let in, those learned men beheld for the first time the object of their curiosity, and learned that, whilst each was correct in what he had said, all differed widely from the truth.

Though a pantheist, Jalaluddin lays great stress on the fact of man's sinfulness and frailty and on the personality of the Devil, as in the following lines:—

Many a net the Devil spreads, weaving snare on snare,

We, like foolish birds, are caught captive unaware;

From one net no sooner free, straightway in another

We are tangled, fresh defeats aspirations smother;

Till upon the ground we lie, helpless as a stone,

We, who might have gained the sky, we, who might have flown.

When we seek to house our grain, pile a goodly store,

Pride, a hidden mouse, is there nibbling evermore;

Till upon the harvest day, lo, no golden heap,

But a mildewed mass of chaff maggots overcreep.

Many a brilliant spark is born where the hammers ply,

But a lurking thief is there; prompt, with finger sly,

Spark on spark he puts them out, sparks which might have soared

Perish underneath his touch. Help us then, O Lord!

What with gin and trap and snare, pitfall and device,

How shall we poor sinners reach Thy fair paradise?

Again, in contradiction to logical pantheism Jalaluddin lays stress on man's free-will and responsibility, as in the following illustration:—

On the frontier set, the warden of a fort,Far from his monarch and his monarch's court,Holds the fort, let foemen bluster as they may,Nor for fear or favour will his trust betray;Far from his monarch, on the empire's edge,He, with his master, keeps unbroken pledge;Surely then his lord his worth will higher own,Than their prompt obedience who surround his throne;In the Master's absence a little work done wellWeighs more than a great one when his eyes compel;Now is the time to show who faith and trust will keep,Once probation over, faith and trust are cheap.

However much individual Sufis may have fallen into Antinomianism and acted as if there was no essential difference between good and evil, the great Sufi teachers have always enjoined self-mortification, quoting the saying, "Die before you die." This dying is divided by them into three kinds: "black death" (suffering oppression from others), "red death" (mortifying the flesh), and "white death" (suffering hunger). Jalaluddin illustrates this by the following parable:—

A merchant from India a parrot had brought,

And pent in a narrow cage, sorrow-distraught

With longing for freedom. One day the good man

Determined to try with his wares Hindustan;

So he said to his parrot, 'What gift shall I bring

From the land you were born in—what curious thing?'

The parrot replied, 'There are kinsfolk of mine

Flying blithe in those woods, for whose freedom I pine;

(Oh, the green woods of India!). Go, tell them my state—

A captive in grip of implacable fate—

And say, "Is it justice that I should despair

While you, where you list, can flash swift through the air,

Can peck at the pineapples, bathe in the springs,

And spread in the sunlight your green-gleaming wings?"

His message the man took, and made his word good

When he came where the parrots flew free in the wood;

But no sooner the message was given than one

Like lead to the earth fell as dead as a stone.

The merchant upbraided himself, 'It is clear

This parrot of mine was a relative dear,

And the shock has been fatal; myself am to blame.

'When his journey was finished and homeward he came,

His parrot inquired, 'Hast brought me a crumb

Of comfort in sorrow where, caged, I sit dumb?'

The merchant said, 'No; 'twas a pity you sent,

For the message you gave proved of fatal content;

As soon as I gave it one shuddered and fell

Stone-dead, as if struck by some magical spell.

'No sooner that bird's fate it heard, than his own

On the floor of its cage fell as dead as a stone

.'Alas!' cried the merchant, 'my own bird I've killed—

My own pretty parrot, so Allah has willed!'

Sadly out from the cage the dead body he drew,

When, to his amazement, straight upwards it flew

And perched on a tree. 'Lo! the message,' he said,

'My friend sent—"Die thou, as I make myself dead,

And by dying win freedom." Farewell, master dear,

I caught the plain hint with intelligence clear.

Thyself reckon dead, and then thou shalt fly

Free, free, from the prison of earth to the sky!

Spring may come, but on granite will grow no green thing;

It was barren in winter, 'tis barren in spring;

And granite man's heart is, till grace intervene,

And, crushing it, clothe the long barren with green.

When the fresh breath of Jesus shall touch the heart's core,

It will live, it will breathe, it will blossom once more.'

The last couplet is a good illustration of the different ways in which Christ is regarded by the Sufi poets and by Mohammed in the Koran. In the latter, it is true, He is acknowledged as the Word of God and the Spirit of God, but His work among men is done, having been entirely superseded by the coming of Mohammed, the last and greatest of the prophets. Jalaluddin on the other hand, as in the above couplet, speaks of Christ as still exercising healing influences. Elsewhere he says, referring to the Gospel narrative of Christ's entry into Jerusalem (not mentioned in the Koran), and taking the ass as the symbol of the body pampered by the sensualist:—

You deserted Jesus, a mere ass to feed,

In a crowd of asses you would take the lead;

Those who follow Jesus, win to wisdom's ranks;

Those who fatten asses get a kick for thanks.

Pity keep for Jesus, pity not the ass,

Let not fleshly impulse intellect surpass.

If an ass could somewhat catch of Jesus' mind,

Classed among the sages he himself would find;

Though because of Jesus you may suffer woe,

Still from Him comes healing, never let Him go.

In another place, speaking of the importance of controlling the tongue because of the general sensitiveness of human nature, he says:—

In each human spirit is a Christ concealed,

To be helped or hindered, to be hurt or healed;

If from any human soul you lift the veil

You will find a Christ there hidden without fail;

Woe, then, to blind tyrants whose vindictive ire,

Venting words of fury, sets the world on fire.

But though he speaks with reverence of Christ, he shares the common Mohammedan animus against St. Paul. As a matter of fact St. Paul is rarely mentioned in Mohammedan writings, but Jalaluddin spent most of his life at Iconium, where, probably, owing to the tenacity of Oriental tradition, traces of St. Paul's teaching lingered. In the first book of the Masnavi a curious story is told of an early corrupter of Christianity who wrote letters containing contradictory doctrines to the various leaders of their Church, and brought the religion into confusion. In this case Jalaluddin seems to have neglected the importance of distinguishing between second-hand opinion and first-hand knowledge, on which he elsewhere lays stress:—

Knowledge hath two wings, Opinion hath but one,

And opinion soon fails in its orphan flight;

The bird with one wing soon droops its head and falls,

But give it two wings and it gains its desire.

The bird of Opinion flies, rising and falling,

On its wing in vain hope of its rest;

But when it escapes from Opinion and Knowledge receives it,

It gains its two wings and spreads them wide to heaven;

On its two wings it flies like Gabriel

Without doubt or conjecture, and without speech or voice.

Though the whole world should shout beneath it,

'Thou art in the road to God and the perfect faith,

'It would not become warmer at their speech,

And its lonely soul would not mate with theirs;

And though they should shout to it,

'Thou hast lost thy way;

And thinkest thyself a mountain and art but a leaf,

'It would not lose its convictions from their censure,

Nor vex its bosom with their loud reproof;

And though sea and land should join in concert,

Exclaiming, 'O wanderer, thou hast lost thy road!'

Not an atom of doubt would fall into its soul,

Nor a shade of sorrow at the scorner's scorn.

(Professor Cowell's translation.)

Like all quietists, Jalaluddin dwells on the importance of keeping the mind unclouded by anger and resentment, as in the following little parable:—

One day a lion, looking down a well,

Saw what appeared to him a miracle,

Another lion's face that upward glared

As if the first to try his strength he dared.

Furious, the lion took a sudden leap

And o'er him closed the placid waters deep.

Thou who dost blame injustice in mankind,

'Tis but the image of thine own dark mind;

In them reflected clear thy nature is

With all its angles and obliquities.

Around thyself thyself the noose hast thrown,

Like that mad beast precipitate and prone;

Face answereth to face, and heart to heart,

As in the well that lion's counterpart.

'Back to each other we reflections throw,

'So spake Arabia's Prophet long ago;

And he, who views men through self's murky glass,

Proclaims himself no lion, but an ass.

As Ghazzali had done before him, Jalaluddin sees in the phenomena of sleep a picture of the state of mind which should be cultivated by the true Sufi, "dead to this world and alive to God":—

Every night, O God, from the net of the body

Thou releasest our souls and makest them like blank tablets;

Every night thou releasest them from their cages

And settest them free: none is master or slave.

At night the prisoners forget their prisons,

At night the monarchs forget their wealth:

No sorrow, no care, no profit, no loss,

No thought or fear of this man or that.

Such is the state of the Sufi in this world,

Like the seven sleepers he sleeps open-eyed,

Dead to worldly affairs, day and night,

Like a pen held in the hand of his Lord.

—(Professor Cowell.)

As we have seen, Jalaluddin's conception of God is a far higher one than is embodied in the orthodox formula of the Koran, "Say: God is One. He neither begetteth nor is begotten." With Jalaluddin God is far more immanent than transcendent. In one place he says, "He who beholdeth God is godlike," and in another, "Our attributes are copies of His attributes." In a remarkable passage anticipating the theory of Evolution he portrays man ascending through the various stages of existence back to his Origin:—

From the inorganic we developed into the vegetable kingdom,Dying from the vegetable we rose to animal,And leaving the animal, we became man.Then what fear that death will lower us?The next transition will make us an angel,Then shall we rise from angels and merge in the Nameless,All existence proclaims, "Unto Him shall we return."

Elsewhere he says:—

Soul becomes pregnant by the Soul of souls

And brings forth Christ;

Not that Christ Who walked on land and sea,

But that Christ Who is above space.

The work of man in this world is to polish his soul from the rust of concupiscence and self-love, till, like a clear mirror, it reflects God. To this end he must bear patiently the discipline appointed:—

If thou takest offence at every rub,

How wilt thou become a polished mirror?

He must choose a "pir," or spiritual guide who may represent the Unseen God for him; this guide he must obey and imitate not from slavish compulsion, but from an inward and spontaneous attraction, for though it may be logically inconsistent with Pantheism, Jalaluddin is a thorough believer in free-will. Love is the keynote of all his teaching, and without free-will love is impossible. Alluding to the ancient oriental belief that jewels are formed by the long-continued action of the sun on common stones, he says:—

For as a stone, so Sufi legends run,

Wooed by unwearied patience of the sun

Piercing its dense opacity, has grown

From a mere pebble to a precious stone,

Its flintiness impermeable and crass

Turned crystalline to let the sunlight pass;

So hearts long years impassive and opaque

Whom terror could not crush nor sorrow break,

Yielding at last to love's refining ray

Transforming and transmuting, day by day,

From dull grown clear, from earthly grown divine,

Flash back to God the light that made them shine.

Jalaluddin did not live to finish the Masnavi, which breaks off abruptly near the end of the sixth book. He died in 1272, seven years after Dante's birth. His last charge to his disciples was as follows:—

I bid you fear God openly and in secret, guard against excess in eating, drinking and speech; keep aloof from evil companionship; be diligent in fasts and self-renunciation and bear wrongs patiently. The best man is he who helps his fellow-men, and the best speech is a brief one which leads to knowledge. Praise be to God alone!

He is buried at Iconium, and his tomb, like those of all Mohammedan saints, in a greater or lesser degree, is a centre of pilgrimage. The reverence with which he is regarded is expressed in the saying current among Moslems:—

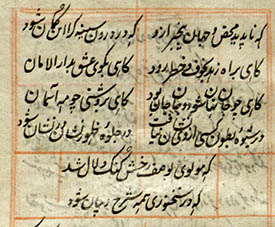

Paigumbar nest, wali darad Kitab

(He is not a prophet, but he has a book)

Copyright © World Spirituality · All Rights Reserved