[This is taken from Henry Sloane Coffin's Some Christian Convictions, originally published in 1915.]

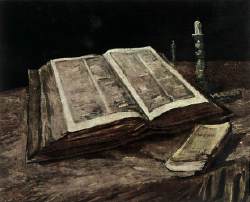

In terms of the definition of religion given in the last chapter, we may describe the Bible as the record of the progressive religious experience of Israel culminating in Jesus Christ, a record selected by the experience of the Jewish and Christian Church, and approving itself to Christian experience today as the Self-revelation of the living God.

The Bible is a literary record. It is not so much a book as a library, containing a great variety of literary forms—legends, laws, maxims, hymns, sermons, visions, biographies, letters, etc. Judged solely as literature its writings have never been equalled in their kind, much less surpassed. Goethe declared, "Let the world progress as much as it likes, let all branches of human research develop to their utmost, nothing will take the place of the Bible—that foundation of all culture and all education." Happily for the English-speaking world the translation into our tongue, standardized in the King James' Bible, is a universally acknowledged classic; and scarcely a man of letters has failed to bear witness to its charm and power. While most translations lose something of the beauty and meaning of the original, there are some parts of the English Bible which, as literature and as religion, excel the Hebrew or Greek they attempt to render.

The Bible is a record of religious experience. It has but one central figure from Genesis to Revelation—God. But God is primarily in the experience, only secondarily in the record. All thought succeeds in grasping but a fraction of consciousness; thought is well symbolized in Rodin's statue, where out of a huge block of rough stone a small finely chiselled head emerges. With all their skill we cannot credit the men of faith who are behind the Bible pages with making clear to themselves but a small part of God's Self-disclosure to them. And when they came to wreak thought upon expression, so clear and well-trained a mind as Paul's cannot adequately utter what he feels and thinks. His sentences strain and some times break; he ends with such expressions as "the love of Christ which passeth knowledge," and God's "unspeakable gift."

The divine revelation which is in the experience has been at times identified with the thought that interprets it, or even with the words which attempt to describe it. "Faith in the thing grows faith in the report"; and fantastic doctrines of the verbal inerrancy of the Bible have been held by numbers of earnest Christians. Certain recent scholars, acknowledging that no version of the Bible now existing is free from error, have put forward the theory that the original manuscripts of these books, as they came from their authors' hands, were so completely controlled by God as to be without mistake. Since no man can ever hope to have access to these autographs, and would not be sure that he had them in his hands if he actually found them, this theory amounts to saying with the nursery rhyme:

Oats, peas, beans, and barley grows,

Where you, nor I, nor nobody knows.

We have not only to collate the manuscripts we possess and try to reconstruct the like liest text, but when we know what the authors probably wrote, we must press back of their language and ideas to the religious experience they attempt to express.

As writers the Biblical authors do not claim a special divine assistance. Luke, in his preface to his gospel, merely asserts that he has taken the pains of a careful historian, and Paul and his various amanuenses did their best with a language in which they were not literary experts. The Bible reader often has the impression that its authors' religious experience, like Milton's sculptured lion, half appears "pawing to get free his hinder parts." Or, to change the metaphor, now one portion of their communion with God is brought to view and now another, as one might stand before a sea that was illuminated from moment to moment by flashes of lightning.

The Bible is the record of an historic religious experience—that of Israel which led up to the consciousness of God in Jesus and His followers. The investigation of the sources of Hebrew religion has shown that many of its beliefs came from the common heritage of the Semitic peoples; and there are numerous points of similarity between Israel's faith and that of other races. This ought not to surprise us, since its God is the God of all men. But the more resemblances we detect, the greater the difference appears. The same legend in Babylonia and in Israel has such unlike spiritual content; the identical rite among the Hebrews and among their neighbors developed such different religious meaning. This particular stream of religious life has a unity and a character of its own. Its record brings into the succeeding centuries, and still produces in our world, a distinctive relationship with God.

The Bible is a record of progressive religious experience. As every poet with a new message has to create his own public, so it would seem that God had slowly to evolve men who would respond to His ever higher inspirations. When scholars arrange for us the Biblical material in its historical order, the advance becomes much more apparent. Its God grows from a tribal deity to the God of the whole world; from a localized divinity dwelling on Sinai or at Jerusalem, as the Greeks placed their gods on Olympus, into the Spirit who fills heaven and earth; from " a man of war" and a tribal lawgiver into the God whose nature is love. "By experience," said Roger Ascham, "we find out a short way by a long wandering," and it took at least ten centuries to pass from the God of Moses to the Father of Jesus Christ.

Obviously we must interpret, and at times correct, the less developed by the more perfect consciousness of God. The Scriptures, like the land in which their scenes are laid, are a land of hills and valleys, of lofty peaks of spiritual elevation and of dark ravines of human passion and doubt and cruelty; and to view it as a level plain of religious equality is to make serious mistakes. Ecclesiastes is by no means on the same level with Isaiah, nor Proverbs with the Sermon on the Mount. Doctrines and principles that are drawn from texts chosen at random from all parts of the Bible are sure to be unworthy statements of the highest fellowship with God.

Nor does mere chronological rearrangement of the material do justice to the progress; there was loss as well as gain. All mountain roads on their way to the summit go down as well as up; and their advance must be judged not from their elevation at any particular point, but from their successful approach towards their destination. The experiences of Israel reach their apex in the faith of Jesus and of His immediate followers; and they find their explanation and unity in Him. In form the Jewish Bible, unlike the Christian, has no climax; it stops, ours ends. Christians judge the progress in the religious experience of Israel by its approximation to the faith and purpose of Jesus.

The Bible is a selected record of religious experience. Old Testament historians often refer to other books which have not been preserved; and there were letters of St. Paul which were allowed to perish, and gospels, other than our four, which failed to gain a place in the Canon. A discriminating instinct was at work, judging between writings and writings. We know little of the details of the process by which it compiled the Old Testament. The Jewish Church spoke of its Scriptures as "the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings"; and it is probable that in this order it made collections of those books which it found expressed and reproduced its faith. In the time of Jesus the Old Testament, as we know it, was practically complete, although there still lingered some discussion whether Esther, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs were sacred books. We should like to know far more than students have yet discovered of the reasons which Jewish scholars gave for admitting some and rejecting other writings; but, whatever their alleged reasons, the books underwent a struggle for recognition, and the fittest, according to the judgment of the corporate religious experience of the devout, survived.

The first Christians found the Jewish Bible in use as containing "the oracles of God"; and as it had been their Lord's Bible it became theirs. No one of the first generation of Christians thought of adding other Scriptures. In that age the Coming of the Messiah and His Kingdom in power were daily expected, and there seemed no need of writing anything for succeeding times. Paul's letters were penned to meet current needs in the churches, and were naturally kept, reread and passed from church to church. As the years went by and disciples were added who had never known the Lord in the days of His flesh, a demand arose for collections of His sayings. Then gospels were written, and the New Testament literature came into existence, although no one yet thought of these writings as Holy Scripture.

Three factors, however, combined to give these books an authoritative position. In the Church services reading was a part of worship. What should be read? A letter of an apostle, a selection of Jesus' sayings, a memoir of His life, an account of the earliest days of the Church. Certain books became favorites because they were most helpful in creating and stimulating Christian faith and life; and they won their own position of respect and authority.

Some books by reason of their authorship—Paul or Peter, for instance—or because they contained the life and teaching of Jesus, naturally held a place of reverence. This eventually led to the ascription to well-known names of books that were found helpful which had in fact been written by others. For example, the Epistle to the Hebrews was ultimately credited to Paul, and the Second Epistle of Peter to the Apostle Peter.

And, again, controversies arose in which it was all important to agree what were the sources to which appeal should be made. The first collection of Christian writings, of which we know, consisting of ten letters of Paul and an abridged version of the Gospel according to Luke, was put forth by Marcion in the Second Century to defend his interpretation of Christianity—an interpretation which the majority of Christians did not accept. It was inevitable that a fuller collection of writings should be made to refute those whose faith appeared incomplete or incorrect.

In the last quarter of the Second Century we find established the conception of the Bible as consisting of two parts—the Old and the New Covenant. This meant that the Christian writings so acknowledged would be given at least the same authority as was then accorded to the Jewish Bible. Early in the Fourth Century the historian, Eusebius, tells us how the New Testament stood in his day. He divides the books into three classes—those acknowledged, those disputed, and those rejected. In the second division he places the epistles of James and Jude, the Second Epistle of Peter and the Second and Third of John; in the first all our other books, but he says of the Revelation of John, that some think that it should be put in the third division; in the third he names a number of books which are of interest to us as showing what some churches regarded as worthy of a place in the New Testament, and used as they did our familiar gospels and epistles. By the end of that century, under the influence of Athanasius and the Church in Rome, the New Testament as it now stands became almost everywhere recognized.

The reason given for the acceptance or rejection of a book was its apostolic authorship. Only books that could claim to have been written by an apostle or an apostolic man were considered authoritative. We now know that not all the books could meet this requirement; but the Church's real reason was its own discriminating spiritual experience which approved some books and refused others. Canon Sanday sums up the selective process by saying: "In the fixing of the Canon, as in the fixing of doctrine, the decisive influence proceeded from the bishops and theologians of the period 325-450. But behind them was the practice of the greater churches; and behind that again was not only the lead of a few distinguished individuals, but the instinctive judgment of the main body of the faithful. It was really this instinct that told in the end more than any process of quasi-scientific criticism. And it was well that it should be so, because the methods of criticism are apt to be, and certainly would have been when the Canon was formed, both faulty and inadequate, whereas instinct brings into play the religious sense as a whole. Even this is not infallible; and it cannot be claimed that the Canon of the Christian Sacred Books is infallible. But experience has shown that the mistakes, so far as there have been mistakes, are unimportant; and in practice even these are rectified by the natural gravitation of the mind of man to that which it finds most nourishing and most elevating."

In their attitude towards the Canon all Christians agree that the books deemed authoritative must record the historic revela tion which culminated in Jesus and the founding of the Christian Church. A Roman Catholic may derive more religious stimulus from the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola than from the Book of Lamentations, and a Protestant from Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress than from the Second Epistle of John; but neither would think of inserting these books in the Canon. He who finds as much religious inspiration in some modern poet or essayist as in a book of the Bible, may be correctly reporting his own experience; but he is confusing the purpose of the Bible if he suggests the substitution of these later prophets for those of ancient Israel. The Bible is the spiritually selected record of a particular Self-disclosure of God in a national history which reached its religious goal in Jesus Christ.

Romanists and Protestants differ as to how many books constitute the Canon, the former including the so-called Apocrypha—books in the Greek translation but not in the original Hebrew Bible. And they differ more fundamentally in the principle underlying the selection of the books. The Roman Catholic holds that it is the Church which officially has made the Bible, while the Protestant insists that the books possess spiritual qualities of their own which gave them their place in the authoritative volume, a place which the Church merely recognized. Luther, in his celebrated dispute with Dr. Eck, asserted: "The Church cannot give more authority or force to a book than it has in itself. A Council cannot make that be Scripture which in its own nature is not Scripture." The Council of Trent, answering the Reformers, in 1546, issued an official decree defining what is Scripture: "The holy, ecumenical and general Synod of Trent, legitimately convened in the Holy Ghost...receives and venerates with an equal piety and reverence all the books as well of the Old as of the New Testament ...together with the traditions pertaining both to faith and to morals, as proceeding from the mouth of Christ, or dictated by the Holy Spirit, and preserved in the Church Catholic by continuous succession." Then follows a catalogue of the books, and an anathema on all who shall not receive them "as they are contained in the old vulgate Latin version."

Over against this the Protestant takes the position that the books of the Scripture came to be recognized as authoritative exactly as Shakespeare, Milton and Wordsworth have been accorded their place in English literature. It was the inherent merit of Hamlet and Paradise Lost and the Ode on the Intimations of Immortality that led to their acknowledgment. No official body has made Shakespeare a classic; his works have won their own place. No company of men of letters officially organized keeps him in his eminent position; his plays keep themselves. The books of the Bible have gained their positions because they could not be barred from them; they possess power to recanonize themselves. Some are much less valuable than others, and it is, perhaps, a debatable question whether one or two of the apocryphal books—First Maccabees, or Ecclesiasticus, for instance—are not as spiritually useful as the Song of Solomon or Esther; but of the chief books we may confidentially affirm that, if one of them were dug up for the first time today, it would gradually win a commanding place in Christian thought. And it is a similar social experience of the Church—Jewish and Christian—which has recognized their worth. The modernist Tyrrell has written: "It cannot be denied that in the life of that formless Church, which underlies the hierarchic organization, God's Spirit exercises a silent but sovereign criticism, that His resistlessly effectual judgment is made known, not in the precise language of definition and decree, but in the slow manifestation of practical results; in the survival of what has proved itself life-giving; in the decay and oblivion of all whose value was but relative and temporary."

In a sense each Protestant Christian is entitled to make up a Bible of his own out of the books which record the historical discoveries of God. He is not bound by the opinions of others, however many and venerable; and unless a book commends itself to his own spiritual judgment, he is under no obligation to receive it as the word of God to him. As a matter of fact every Christian does make such a Bible of his own; the particular passages which "grip" him and reproduce their experiences in him, they, and they alone, are his Bible. Luther was quick ened into life by the epistles of Paul, but spoke slightingly of James; many socially active Christians in our day live in the prophets and the first three gospels, and almost ignore the rest of the Bible. But individual taste, while it has preferred authors and favorite works, does not think of denying to Milton, or Wordsworth, or Shelley, their place among English classics; a social judgment has assigned them that. A man who is not hopelessly conceited will regret his inability to appreciate a single one of the great authors, and will try to enlarge his sympathies. The Christian will, with entire naturalness, be loyal to so much of the Bible as "finds him," and humbly hope and endeavor to be led into ampler ranges of spiritual life, that he may "apprehend with all saints" the breadth, length, depth and height of the historic Self-revelation of God.

The Bible is thus a standard of religious experience. If there is any question as to what man's life with God ought to be, it can be referred to the life recorded in these books. But men have often made the Bible much more; confusing experience with its interpretation in some particular epoch, they used the Bible as a treasury of proof texts for doctrines, or of laws for conduct, or of specific provisos for Church government and worship. They forgot that the writers of the early chapters of Genesis, in describing their faith in God's relationship to His world and to man and to history, had to express that faith in terms of the existing traditions concerning the creation, the fall, the deluge, the patriarchs. Their faith in God is one thing; the scientific and historic accuracy of the stories in which they utter it is quite another thing. They did not distinguish between Paul's life with God in Christ, and the philosophy he had learned in Gamaliel's classroom, or picked up in the thought of the Roman world of his day. Paul's religious life is one thing, his theology in which he tries to explain and state it is another thing. They read the plans that were made for the organization of the first churches, and hastily concluded that these were intended to govern churches in all ages. The chief divisions of the Church claim for their form of government—papal, episcopal, presbyterian, congregational—a Biblical authority. The religious life of the early churches is one thing; their faith and hope and love ought to abide in the Church throughout all generations; the method of their organization may have been admirable for their circumstances, but there is no reason we should consider it binding upon us in the totally different circumstances of our day. Latterly social reformers have been attempting to show that the Bible teaches some form of economic theory, like socialism or communism. It lays down fundamental principles of brotherhood, of justice, of peaceableness, but the economic or political systems in which these shall be embodied, we must discover for ourselves in each age. It is the norm of our life with God; but it is not a standard fixing our scientific views, our theological opinions, our ecclesiastical polity, our economic or political theories. It shows forth the spirit we should manifest towards God and towards one another as individuals, and families, and nations; "and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty."

This brings us to the question of the authority of the Bible. There are two views of its authority; one that it contains mys teries beyond our reason, which are revealed to us, and guaranteed to us as true, either by marvellous signs such as miracles and fulfilled prophecies, or by the infallible pronouncement of the official Church; the other is that the Bible is the revelation of self-evidencing truth. The test of a revelation is simply that it reveals. The evidence of daylight lies in the fact that it enables us to see, and as we live in the light we are more and more assured that we really do see. Advocates of the former position say: "If anything is in the Bible, it must not be questioned; it must simply be accepted and obeyed." Advocates of the latter view say: "If it is in the Bible, it has been tried and found valuable by a great many people; question it as searchingly as you can, and try it for yourself, and see whether it proves itself true or not."

These two views came into collision in the struggle for a larger faith which we call the Reformation. Augustine had stated the position which became traditional when he wrote, "I would not believe in the Gospel without the authority of the Church." But Luther insisted on the contrary: "Thou must not place thy decision on the Pope, or any other; thou must thyself be so skilful that thou can'st say, 'God says this, not that.' Thou must bring conscience into play, that thou may'st boldly and defiantly say, 'That is God's word; on that will I risk body and life, and a hundred thousand necks if I had them.' Therefore no one shall turn me from the word which God teaches me, and that must I know as certainly as that two and three make five, that an ell is longer than a half. That is certain, and though all the world speak to the contrary, still I know that it is not otherwise. Who decides me there? No man, but only the Truth which is so perfectly certain that nobody can deny it." And Calvin took the same ground: "As to their question, How are we to know that the Scriptures came from God, if we cannot refer to the decree of the Church, we might as well ask, How are we to distinguish light from darkness, white from black, bitter from sweet."

The truth of the religious experiences recorded in the Bible is self-evidencing to him who shares these experiences, and to no one else. The Bible has, in a sense, to create or evoke the capacities by which it is appreciated and verified. It is inspired only to those who are themselves willing to be controlled by similar inspirations; it is the word of God only to those who have ears for God's voice. There is a difference between the phrases: "It is certain," and "I am certain." In other matters we appeal to the collective opinion of sane people; but such knowledge does not suffice in religion. Our fellowship with God must be our own response to our highest inspirations. The Bible is authoritative for us only in so far as we can say: "I have entered into the friendship of the God, whose earlier friendship with men it records, and know Him, who speaks as personally to my conscience through its pages, as He spake to its writers. The Spirit that ruled them, the Spirit of trust and service, controls me." This is John Calvin's position. "It is acting a preposterous part," he writes in his Institutes, "to endeavor to produce sound faith in the Scriptures by disputations. Religion appearing to profane men to consist wholly in opinion, in order that they may not believe anything on foolish or slight grounds, they wish and expect it to be proved that Moses and the prophets spake by divine inspiration; but as God alone is a sufficient witness of Himself in His own word, so also the word will never gain credit in the hearts of men, till it is confirmed by the testimony of the Spirit."

If, then, the authority of the Bible depends upon the witness of the Spirit within our own souls, its authority has definite limits. We can verify spiritually the truth of a religious experience by repeating that experience; but we cannot verify spiritually the correctness of the report of some alleged event, or the accuracy of some opinion. We can bear witness to the truthfulness of the record of the consciousness of shame and separation from God in the story of the fall of Adam and Eve; we must leave the question of the historicity of the narrative and the scientific view of the origin of the race in a single pair to the investigations of scholars. Our own knowledge of Jesus Christ as a living Factor in our careers confirms the experience His disciples had of His continued intercourse with them subsequent to His crucifixion; but the manner of His resurrection and the mode in which post mortem He communicated with them must be left to the untrammelled study of historical students. The religious message of a miraculous happening, like the story of Jonah or of the raising of Lazarus, we can test and prove: disobedience brings disaster, repentance leads to restoration; faith in Christ gives Him the chance to be to us the resurrection and the life. The reported events must be tested by the judgments of historic probability which are applied to all similar narratives, past or present. The Bible's authority is strictly religious; it has to do solely with God and man's life with man in Him; and, when read in the light of its culmination in Christ, it approves itself to the Spirit of Christ within Christians as a correct record of their experiences of God, and the mighty inspiration to such experiences. Surely it is no belittling limitation to say of this unique book that it is an authority only on God. Every fundamental question of life is answered, every essential need of the soul is met, when God is found, and becomes our Life, our Home.

And with such self-evidencing authority in the books of the Bible, it is a question of minor importance who were their authors and when they were written—the questions which the literary historical criticism undertakes to answer. Luther put the matter conclusively when he said in his vigorous fashion: "That which does not teach Christ is not apostolic, though Peter or Paul should have said it; on the contrary that which preaches Christ is apostolic, even if it should come from Judas, Annas, Pilate and Herod." Some persons have been greatly troubled in the last generation by being told that scholars did not consider the conventionally received authorships of many of the books of the Bible correct, but thought that Moses did not write the Pentateuch, or David the Psalms, or Solomon the Proverbs or Ecclesiastes, or Isaiah and Jeremiah more than parts of the books that bear their names, or John and Peter all the writings ascribed to them. We are not to judge of writings by their authors, but by their intrinsic value. Suppose Shakespeare did not write more than a fraction of the plays associated with his name, or that he wrote none of them at all; the plays themselves remain as valuable as ever; their interpretation of life in its tragedy and humor, its heights and its depths, is as true as it ever was. Whatever views of their composition or authorship may be reached by literary experts, the Scriptures possess exactly the same spiritual power they have always possessed. The Lord has been "our dwelling-place in all generations," whether Moses or some other psalmist penned that line; and Jesus is the bread of life, whether the apostle John or some other disciple whom Jesus loved records that experience. Scholars may make the meaning of the Scriptures much plainer by their searching studies; and they must be encouraged to investigate as minutely and rigorously as they can. To be fearful that the Bible cannot stand the test of the keenest study, is to lack faith in its divine vitality. To found a "Bible Defence League" is as unbelieving as to inaugurate a society for the protection of the sun. Like the sun the Bible defends itself by proving a light to the path of all who walk by it. The only defence it needs is to be used; and the only attack it dreads is to be left unread.

And in speaking of the authority of the Bible we cannot forget that it is not for Christians the supreme authority. "One is your Master, even Christ." We must be cautious in speaking of the Bible, as we commonly do, as "the word of God." That title belongs to Jesus. The Bible contains the word of God; He is for us the Word of God. We dare not overlook His untrammelled attitude towards the Scriptures of His people, who let His own spiritual discernment determine whether a Scripture was His Father's living voice to Him, or only something said to men of old time, and given temporarily for the hardness of hearts that could respond to no higher ideal. As His followers, we dare not use less freedom ourselves. We test every Scripture by the Spirit of Christ in us: whatever is to us unchristlike in Joshua or in Paul, in a psalmist or in the seer on Patmos, is not for us the word of our God: whatever breathes the Spirit of Jesus from Genesis to Revelation is to us our Father's Self-revealing speech.

Nor do we think that God ceased speaking when the Canon of the Bible was complete. How could He, if He be the living God? "Truth," said Milton, "is compared in Scrip ture to a streaming fountain; if her waters flow not in a perpetual progression, they sicken into a muddy pool of conformity and tradition." The fountain of God's Self-revealing still streams. Religious truth comes to us from all quarters—from events of today and contemporaneous prophets, from living epistles at our side and the still small voice within; but as a simple matter of fact, its main flow is still through this book. When we want God—want Him for our guidance, our encouragement, our correction, our comfort, our inspiration—we find Him in the record of these ancient experiences of His Self-unveiling. When near his death, after years of agony on his bed, when he himself had become a changed man, Heinrich Heine wrote: "I attribute my enlightenment entirely and simply to the reading of a book. Of a book? Yes! and it is an old homely book, modest as nature—a book which has a look modest as the sun which warms us, as the bread which nourishes us—a book as full of love and blessing as the old mother who reads in it with her trembling lips, and this book is the Book, the Bible. With right is it named the Holy Scriptures. He who has lost his God can find Him again in this book; and he who has never known Him, is here struck by the breath of the Divine Word."

Copyright © World Spirituality · All Rights Reserved