Art In The Service of Religion

By Dewitt H. Parker, Excerpted from The Principles of Aesthetics.

By Dewitt H. Parker, Excerpted from The Principles of Aesthetics.

The distinctive purpose of art, so we have argued throughout this study, is culture, the enrichment of the spirit. But lovers of art have always claimed for it more active and broader influences. To my thinking, most of such claims, especially in our age, like similar claims for religion, are greatly exaggerated. Passion, convention, economic fact in the largest sense, practical intelligence, these are the dominant forces swaying men, not beauty, not religion. Indeed, one who would compare the influence of art upon life at the present time with its influence upon primitive societies might infer the early extinction of that influence altogether.

For among primitive men the influence of art is all-pervading. With them art is inseparable from utility and communal activities, upon which it has an immediate modifying or strengthening effect. The movement of civilization, with the exception of the Greek, medieval, and renaissance city states, has involved a breaking away from this original unity until, among ourselves, art is developed and enjoyed in isolation from the rest of life. Art is valued for its own sake, for its contribution to culture, not for any further influence upon life, and this freedom has come to be part of its very meaning. Instead of being interested only in pictures and statues representing ourselves, our rulers, our gods, or our neighborhood, we enjoy imitations of people who have had no effect upon our lives whatever and scenes which we have never visited, and we repair to museums to see them; instead of employing music to beautify our daily life, we leave that life for the concert hall, where we shut ourselves away for a few hours of “absolute” musical experience. Prose literature and the drama, when inspired by contemporary social problems, offer exceptions to this isolation, for through their ability to express ideas they can exert a more pervasive influence.

Although social problems are solved in obedience to forces and demands beyond the control of artists, literary expression is effective in persuading and drawing into a movement men whose status would tend to make them hostile or indifferent, as in Russia, where numerous men and women of the aristocratic and wealthy classes became revolutionaries by reason of literature. And yet the literary arts also have acquired a large measure of isolation and independence. A play representing Viennese life is appreciated in New York, a novel of contemporary manners in England is enjoyed in America. Literature does not depend for its interest upon its ability to interpret and influence the life that the reader himself lives; he values it more because it extends than because it reflects that life. People decry art for art’s sake, but in vain.

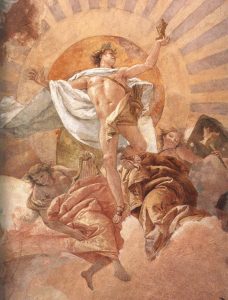

The development of the relation of religion to life has been parallel to the development of art. Originally, religion penetrated every activity; now, by contrast, it has been removed from one after another of the major human pursuits. Agriculture, formerly undertaken under the guidance of religion; science, once the prerogative of the priesthood; art, at one time inseparable from worship; politics, once governed by the church and pretending a divine sanction; war, until yesterday waged with the fancied cooperation of the gods—even these are now under complete secular control. To be sure, there is some music, sculpture, painting, and poetry still in the service of religion, but its relative proportion is small; kings and congresses still appeal for divine aid in times of crisis, but that is perfunctory; men still pray for rain during drought, but without faith. No one would pretend that our commerce and manufacturing have any direct relation to religion.

People still invoke divine authority for moral prescriptions, but the sanctions actually operating are social instincts and fear of public opinion and the law. Religion retains a direct and potent influence only in the institution of marriage, the experience of death, philosophy, and the social life and charities conducted by the churches. Yet even in these spheres the influence is declining, and, so far as it persists, is becoming indirect. Civil and contractual marriage are slowly supplanting religious marriage; there are thousands living in our large cities who do not feel the need of the church to establish and cement their social life; most philosophers disclaim any religious motive or authority for their investigations or beliefs. Only over death does religion still hold undisputed sway.

However, despite the separation of religion and art from life, they may continue to exert influence upon it. But, barring some new integration of the sundered elements of our culture, which we may deeply desire but cannot predict, this influence must be indirect and subtle, and must occur independent of any institutional control. In the case of both it consists in imparting to life a new meaning and perfection, thus making possible a more complete affirmation of life and a freer and more genial attitude and conduct.

For unless the spirit of art or of religion is infused into life, we never find it quite satisfactory. To be sure, men sometimes think they find perfection in certain things—in practical or moral endeavor, in love or in pleasure; but unless art or religion is mixed into them, they always prove to be, in the end, disappointing. No practical purpose is ever quite successful; there is always some part of the plan left unaccomplished; and the success itself is only momentary, for time eventually engulfs it and forgets it. Practical life does not produce any permanent and complete work; its task is done only to be done over again; every house has to be repaired or torn down, every road rebuilt; every invention is displaced by a new one.

This is true even on the higher planes of practical life, in political and social reconstruction. Certain evils may be removed, certain abuses remedied, but new ones always arise to take their places; and even when the entire system is remodeled and men think that the day of freedom and justice has dawned at last, they find, after a generation, a new tyranny and a new injustice. The movement of life makes it impossible for any plan to long endure. Hence the disillusion, the feeling of futility that so often poisons the triumphs of practical men. And without the spirit of art or of religion even love does not satisfy. For imagination creates the perfection of its object and, aside from institutional bonds fast loosening, a faith in the continued growth with one another and with a child, which is essentially religious, creates the permanence and meaning of its bond. Love’s raptures, in so far as they are instinctive, are, of course, independent of any view of life; but apart from imagination and faith in one another, love does not keep its quality or renew itself in memory, nor can it survive death which always impends to destroy. Men often seek escape from the feeling of imperfection in frivolity, but ennui is the inevitable consequence, and reflection with its doubts cannot be stilled.

By contrast, in the religious experience and in beauty men feel that they find perfection; hence the attitude of self-surrender and joyousness characterizing both. The abandon of the spectator who decrees that for the moment his life shall be that of the work of art, is matched in the mystical experience by the emotion expressed in Dante’s line, “In his will is our peace.” And in both the self-surrender is based on a felt harmony between the individual and the object—the beautiful thing appeals to the senses, its form is adapted to the structure of the mind, its content is such as to win interest and sympathy; the divine is believed to realize and quiet all of our desires. But while in beauty we feel ourselves at home with the single object, in religion we feel at rest in the universe.

By contrast, in the religious experience and in beauty men feel that they find perfection; hence the attitude of self-surrender and joyousness characterizing both. The abandon of the spectator who decrees that for the moment his life shall be that of the work of art, is matched in the mystical experience by the emotion expressed in Dante’s line, “In his will is our peace.” And in both the self-surrender is based on a felt harmony between the individual and the object—the beautiful thing appeals to the senses, its form is adapted to the structure of the mind, its content is such as to win interest and sympathy; the divine is believed to realize and quiet all of our desires. But while in beauty we feel ourselves at home with the single object, in religion we feel at rest in the universe.

When religion and art are separated from the other parts of life, as they are fast becoming now, the peculiar quality of the experiences which they offer can be rendered universal only by freely infusing it everywhere, through faith, in the case of the one, through imaginative re-creation, in the case of the other. The religious experience is a seeming revelation of a perfect meaning in life as a whole; this meaning must now be imparted to the details of life. By a free act of faith the scattered and imperfect fragments must be built into a purposive unity. The poisonous feeling of futility, will then be lost; each task, no matter how petty or ineffectual, will become momentous as contributing something toward the realization of a good beyond our little existence; and we, however lowly, will find ourselves sublime as instruments of destiny. There is nothing vain to him who believes. And if the believer cannot build a meaning into history and social life as he knows them empirically, he may extend them by faith in a future life, through which his purposes will be given the promise of eternity and the tie between parents and children, friends and lovers and co-workers, an invincible seriousness and worth. Being at peace with the universe, he may be reconciled to the accidents of his life as expressions of its Will.

The method of reconciliation through religion can well be understood by its effect on the attitude towards evil. To one who has faith in the world as perfect, evil becomes an illusion that would disappear to an adequate vision of the Divine. The supposedly evil thing becomes really a good thing—a necessary means to the fulfillment of the divine plan, either in the earthly progress of humanity or in the future life; or if the more mystical types of religion provide the starting point, where individuality itself is felt to be an illusion, a factor in the self-realization of the Absolute. The evil thing remains, of course, what it was, but the interpretation, and therefore the attitude towards it, is transformed. Pain, sorrow, and misfortune become agents for the quickening of the spirit, death a door opening to unending vistas.

The attitude of faith is not embodied in dogmatic and speculative religious doctrines alone; for it finds expression in other beliefs—in progress, in the possibility of a sunny social order, in the perpetuity of human culture, in the peculiar mission of one’s race or country. Such beliefs are expressions primarily of faith, not of knowledge; like religion, they are interpretations of life based on aspiration, not on evidence; and through them men secure the same sort of re-enforcement of motive, courage, and consolation that they derive from the doctrines called religious. But the sphere of faith is wider even than this; the almost instinctive belief that each man has in his own longevity and success, the trust in the permanence of friendship and love, the confidence in the unique value of one’s work or genius—these are also convictions founded more on desire than on knowledge, and may function in the same way as religion in a man’s life.

The re-affirmation of life which art may inspire is independent of any belief or faith about the world. It occurs rather through the application to the objects and incidents of life of a spirit and attitude borrowed from artistic creation and appreciation. It is a generalization of the aesthetic point of view to cover life as well as art; an attempt to bring beauty from art into the whole of life. Although to-day works of art themselves are severed from direct contact with the rest of life, something of the intention and method of the artist may linger and be carried over into it. Art, the image of life, may now serve as a model, after which the latter, in its turn, will be patterned.

The spirit of art has two forms, one constructive, the other contemplative, and both may be infused into life. When the former is put there, each act and task is performed as if it were a work of art. This involves “throwing the whole self” into it, not only thought and patience, but enthusiasm and loving finish, even as the artist puts them into his work, so that it becomes a happy self-expression. Nothing shall interfere with or mar it, or spoil its value when recalled. The imperfection and transiency of the result are then forgotten in the inspiration of endeavor; and the work or act, no matter how insignificant, becomes perfect as an experience and as a memory. The generations may judge it as they will, but as an expression of the energies of my own soul, it is divine. Of course, from the industry of our time, where most work is mechanical and meaningless to him who performs it, the spirit of art has largely fled. Yet there still remain tasks which we all have to execute, if not in business, then at home, which, by arousing our interest and invention, may become materials for the spirit of art. We have at least our homes, our pleasures, our relations with one another, our private adventures, where we can still be free and genial and masterly. And for our work, art will continue to be an ideal, sorrowfully appealing.

The scope of the spirit of art may be extended beyond the single task or act to embrace the whole of one’s life. Impulse offers a plastic material to which form may be given. The principles of harmony, balance, evolution, proper subordination, and perfection of detail, indispensable to beauty in art, are conditions of happiness in life. The form of a work of art and the form of a happy life are the same, as Plato insisted. In order to yield satisfaction, the different parts of life must exemplify identity of motive, continuity and orderliness in the fulfillment of purpose, lucidity of relation, yet diversity for stimulation and totality. There must be a selective scheme to absorb what is congenial and reject the unfit. This sense for form in life may lead to the same results as morality, but the point of departure and the sanction are different. Morality is largely based on conformity, on submission to the general will, and is rendered effective by fear of public disapproval and supernatural taboos; while the aesthetic direction of life has its roots in the love of form and meaning, and its sanction in personal happiness. Moreover, to the reflective person, looking before and after, life has the same sort of reality as a story, and is bound to be judged in some measure like a story. The past and the future live only in the imagination, and when we survey them there they may please us with their interest, liveliness, and meaning, much as a work of art would, or displease us with their vanity and chaos. In this way personality may acquire an imaginative value fundamentally aesthetic. This is different from moral value, which has reference to the relation of a life to social ideals; it is more comprehensive than the religious judgment, which is interested only in saving the soul; because it includes every element of life,—sense, imagination, and achievement, welcoming all, so long as they contribute something to a significant, moving whole.

The feeling for perfection of form and imaginative meaning in life is no invention of philosophers and aesthetes, but part of the normal reaction to conduct. Everybody feels that certain acts, or even certain wishes, are to be rejected by himself, not because they are intrinsically bad or wrong, but because they are inconsistent with his particular nature, and, on the other hand, that there are certain interests that should be cultivated, not because they are universally right or good, but because they are needed to give his life complete meaning. And again, all except the meanest and most repressed souls desire somewhat to shine, if not in the world at large, at least among their friends, and act with a view to appearance and to some total survey of their lives that would consider not merely its goodness or usefulness, but its imaginative emotional appeal. This appeal is the strongest on the death of a great man; this lives longest in the memory. The love of the romantic and adventurous is partly instinctive, but largely imaginative, for it has in view not merely the rapturous pleasures of the hazardous moment, but the remembered delights of recall and expression to others. The love of glory is also imaginative, a feeling for the dramatic extending even beyond the grave. The ambitious man seeks to make a story out of his life for posterity to read and remember, just as the artist makes one out of fictitious material. More might develop out of this love of form and drama in life. We have it to a certain degree of cultivation in picturesque and refined manners, dress, and ceremonial, but even there it is hampered through conventionality and want of invention; further evolved and extended into the deeper strata of life, it would lead to a more interesting and productive existence. Surely, if God is an artist as well as a judge, he will welcome into heaven not only those who have lived well, but also those who have lived beautifully.

There is no necessity, finally, why the constructive spirit of art should be confined to the personal life and should not, in some measure at least, penetrate the community and even the state. By appealing to imaginative feeling, the activities of various individuals and groups, when coordinated and given a purposeful unity, produce an aesthetic effect. The organization of a business or a university may easily come to have such a value for one who has helped to create it, especially if the place where the communal spirit operates is beautiful,—the office, the campus, the shop. Seldom, to be sure, do we find this value in our busy and haphazard America, but in many quarters the intention to create it is awake. As for the state, it is, of course, too little dominated by disinterested intelligence to be beautiful; yet Plato’s ideal of statecraft as a fine art still rules the innermost dream of men.

The contemplative spirit of art is perhaps more important than the constructive in its application to life. Not that any sharp line can be drawn between them, for contemplation must always attend or follow creation, to judge and enjoy; yet towards that part of life which we cannot control, our attitude must be rather that of the spectator than the creator. We cannot interfere with the greater part of life; we can, however, observe it and, in the imagination, transform it, where we can then envisage it as we should a work of art. As we watch it, life itself may become beautiful, and instead of giving ourselves to it half-heartedly and with reserve, we shall accept it with something of the abandon of passionate love,—“In thee my soul hath her content so absolute.” To this end it is necessary to detach life from our more selfish interests and ambitions, from the habits of thought, annoying and preoccupying, that relate to self alone. To the worldly and self-centered, life is interesting only so far as it refers to pride or ambition or passion; otherwise it is indifferent, as none of their concern. But to the religious and to the aesthetically minded, there is no part of life that may not be of interest; to the former, because they impute something of transcendent perfection to it all; to the latter, because they have set themselves the inexhaustible task of its free, imaginative appreciation.

To this end, it is also necessary, after learning to view life objectively and impersonally, to attend to it leisurely and responsively, as we should to a work of art, allowing full scope to the disinterested feelings of curiosity, pity, sympathy, and wonder to create emotional participation.

Then the world may become for us the most magnificent spectacle of all. To imaginative feeling, every landscape is a potential painting, every life-story a romance, history a drama, every man or woman a statue or portrait. Beauty is everywhere, where we who are perhaps not artists but only art lovers can find it; we cannot embody it in enduring form or throw over it the glamour of sensuous loveliness, but we can perceive it with that free appreciation that is the essence of art. And for this, of course, the artists have prepared us; it is they who, by first exhibiting life as beautiful in art, have shown us that it may be beautiful as mirrored in the observing mind. One region after another has been conquered by them. The poets and the painters created the beauty of the mountains, of windmills and canals, of frozen wastes and monotonous prairies, of peasants and factories and railway stations and slums. Themselves the first to feel the value of these things, through some personal attachment or communion with them, they have made it universal through expression. Their works have become types through which we apperceive and appreciate the world: we see French landscapes as Lorrain and Corot saw them, peasants after the fashion of Millet, the stage after Degas. In vain men have prophesied limits to the victorious advance of art. Just at the time when, in the middle of the last century, some men feared that science and industry had banished beauty from the world, the impressionists and realists disclosed it in factory and steamboat and mine. In this way modern art, which might seem through its isolation to have taken beauty away from the world to itself, has given it back again.

Then the world may become for us the most magnificent spectacle of all. To imaginative feeling, every landscape is a potential painting, every life-story a romance, history a drama, every man or woman a statue or portrait. Beauty is everywhere, where we who are perhaps not artists but only art lovers can find it; we cannot embody it in enduring form or throw over it the glamour of sensuous loveliness, but we can perceive it with that free appreciation that is the essence of art. And for this, of course, the artists have prepared us; it is they who, by first exhibiting life as beautiful in art, have shown us that it may be beautiful as mirrored in the observing mind. One region after another has been conquered by them. The poets and the painters created the beauty of the mountains, of windmills and canals, of frozen wastes and monotonous prairies, of peasants and factories and railway stations and slums. Themselves the first to feel the value of these things, through some personal attachment or communion with them, they have made it universal through expression. Their works have become types through which we apperceive and appreciate the world: we see French landscapes as Lorrain and Corot saw them, peasants after the fashion of Millet, the stage after Degas. In vain men have prophesied limits to the victorious advance of art. Just at the time when, in the middle of the last century, some men feared that science and industry had banished beauty from the world, the impressionists and realists disclosed it in factory and steamboat and mine. In this way modern art, which might seem through its isolation to have taken beauty away from the world to itself, has given it back again.

The spirit of art, no less than of religion, can help us to triumph over the evils of life. There are three ways of treating evil successfully: the practical way, to overcome it and destroy it; the religious way, by faith to deny its existence; the aesthetic way, to rebuild it in the imagination. The first is the way of all strong men; but its scope is limited; for some of the evils of life are insuperable; against these our only recourse is faith or the spirit of art. The method of art consists in taking towards life itself the same attitude that the artist takes towards his materials when he makes a comedy or a tragedy out of them; life itself becomes the object of laughter or of tragic pity and fear and admiration. As we observed in our chapter on “The Problem of Evil in Aesthetics,” laughter is an essentially aesthetic attitude, for it implies the ability disinterestedly to face a situation, although one which opposes our standards and expectations, and to take pleasure in it. All sorts of personal feelings may be mixed with laughter, bitterness and scorn and anger; but the fact that we laugh shows that they are not dominant; in laughter we assert our freedom from the yoke of circumstance and make it yield us pleasure even when it thwarts us. Laughter celebrates a twofold victory, first over ourselves, in that we do not allow our disappointments to spoil our serenity, and second over the world, in that, even when it threatens to render us unhappy, we prevent it. Fate may rob us of everything, but not of freedom of spirit and laughter; oftentimes we must either laugh or cry, but tears bring only relief, laughter brings merriment as well.

Even with the devil laughter may effect reconciliation. Practical men will try to destroy him, but so far they have not succeeded; men of faith will prophesy his eventual ruin, but meanwhile we have to live in his company; and how can we live there at peace with ourselves unless with laughter at his antics and our own vain efforts to restrain them? Surely the age-long struggle against him justifies us in making this compromise for our happiness. We who in our lifetime cannot defeat him can at least make him yield us this bit of laughter for our pains. People who think that laughter at evil is a blasphemy against the good set too high a valuation upon their conventions. No one can laugh without possessing a standard, but to laugh is to recognize that life is of more worth than any ideal and happiness better than any morality.

And if by laughter we cannot triumph over evil, we may perhaps achieve this end by appreciating it as an element in tragedy or pathos. For once we take a contemplative attitude towards life, foregoing praise and blame, there is no spectacle equal to it for tragic pity and fear and admiration. There is a heroism in life equal to any in art, in which we may live imaginatively, and in so living forgive the evil that is its necessary condition. Or, when life is pathetic rather than tragic, suffering and fading and weak rather than strong and steady and resisting, we may win insight from the pitiable reality into the possible and ideal; the shadow of evil will suggest to us the light of the good, and for this vision we shall bless life even when it disappoints our hopes. The very precariousness of values, which is an inevitable accompaniment of them, will serve to intensify their worth for us; we shall be made the more passionately to love life, with the joys that it offers us, because we so desperately realize its transiency. Our knowledge of the inevitability of death and failure will quiet our laments, leaving us at least serene and resigned where our struggles and protests would be unavailing. It is by thus generalizing the point of view of art so that we adopt it towards our own life that we secure the catharsis of tragedy. Instead of letting sorrow overwhelm us, we may win self-possession through the struggle against it; instead of feeling that there is nothing left when the loved one dies, we may keep in memory a cherished image, more poignant and beautiful because the reality is gone, and loving this we shall love life also that has provided it.

Finally, in subtle ways, the influence of art, while remaining indirect, may affect practical action in a more concrete fashion. For silently, unobtrusively, when constantly attended to, a work of art will transform the background of values out of which action springs. The beliefs and sentiments expressed will be accepted not for the moment only, aesthetically and playfully, but for always and practically; they will become a part of our nature. The effect is not merely to enlarge the scope of our sympathies by making us responsive, as all art does, to every human aspiration, but rather to strengthen into resolves those aspirations that meet in us an answering need. This influence is especially potent during the early years of life, before the framework of valuations has become fixed. What young man nursed on Shelley’s poetry has not become a lover of freedom and an active force against all oppression? But even in maturer years art may work in this way. One cannot live constantly with the “Hermes” of Praxiteles without something of its serenity entering into one’s soul to purge passion of violence, or with Goethe’s poetry without its wisdom making one wise to live. The effect is not to cause any particular act, but so to mold the mind that every act performed is different because of this influence.

I would compare this influence to that of friends. Friends may, of course, influence conduct directly and immediately through advice and persuasion, but that is not the most important effect of their lives. More important is the gradual diffusion of their attitudes and the enlightenment following their example. Through living their experiences with them, we come to adopt their valuations as our own; by observing how they solve their problems, we get suggestions as to how to solve ours. Art provides us with a companionship of the imagination, a new friendship. The sympathetic touch with the life there expressed enlarges our understanding of the problems and conditions of all life, and so leads to a freer and wiser direction of our own. On the one hand new and adventurous methods of living are suggested, and on the other hand the eternal limits of action are enforced.

Once more I would compare the influence of art with that of religion. The effect of religion upon conduct is partly due to the institutions with which it is connected and the supernatural sanctions which it attaches to the performance of duty; but partly also, and more enduringly, to the stories of the gods. Now these stories, even when believed, have an existence in the imagination precisely comparable to that of works of art, and their influence upon sentiment is of exactly the same order. They are most effective when beautiful, as the legends of Christ and Buddha are beautiful; and they function by the sympathetic transference of attitude from the story to the believer. Even when no longer accepted as true their influence may persist, for the values they embody lose none of their compulsion. And, although as an interpretation of life based upon faith religion is doubtless eternal, its specific forms are probably all fictitious; hence each particular religion is destined to pass from the sphere of faith to that of art. The Greek religion has long since gone there, and there also a large part of our own will some day go—what is lost for faith is retained for beauty.