Buddhist View of War

By Soyen Shaku, translated by D T Suzuki [1906].

By Soyen Shaku, translated by D T Suzuki [1906].

“This triple world is my own possession. All the things therein are my own children. Sentient or non-sentient, animate or inanimate, organic or inorganic, the ten thousand things in this world are no more than the reflections of my own self. They come from the one source. They partake of the one body. Therefore I cannot rest quiet, until every being, even the smallest possible fragment of existence, is settled down in its proper appointment. I do not mind what long eons it will take to finish this gigantic work of salvation. I work at the end of eternity when all beings are peacefully and happily nestled in an infinite loving heart.”

This is the position taken by the Buddha, and we, his humble followers, are but to walk in his wake.

Why, then, do we fight at all?

Because we do not find this world as it ought to be. Because there are here so many perverted creatures, so many wayward thoughts, so many ill-directed hearts, due to ignorant subjectivity. For this reason Buddhists are never tired of combating all productions of ignorance, and their fight must be to the bitter end. They will show no quarter. They will mercilessly destroy the very root from which arises the misery of this life. To accomplish this end, they will never be afraid of sacrificing their lives, nor will they tremble before an eternal cycle of transmigration. Corporeal existences come and go, material appearances wear out and are renewed. Again and again they take up the battle at the point where it was left off.

But all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas never show any ill-will or hatred toward enemies. Enemies–the enemies of all that is good–are indeed wicked, avaricious, shameless, hell-born, and, above all, ignorant. But are they not, too, my own children for all their sins? They are to be pitied and enlightened, not persecuted. Therefore, what is shed by Buddhists is not blood,–which, unfortunately, has stained so many pages in the history of religion,–but tears issuing directly from the fountain-head of loving kindness.

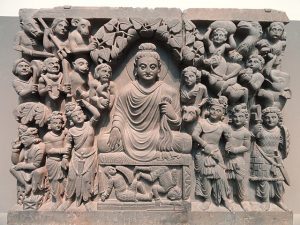

The most powerful weapon ever used by Buddha in the subjugation of his wayward children is the practice of non-atman (non-egotism). He wielded it more effectively than any deadly, life-destroying weapons. When he was under the Bodhi-tree absorbed in meditation on the non-atmanness of things, fiends numbering thousands tried in every way to shake him from his transcendental serenity; but all to no purpose. On the contrary, the arrows turned to heavenly flowers, the roaring clamor to a paradisiacal music, and even the army of demons to a host of celestials. And do you wonder at it? Not at all! For what on earth can withstand an absolutely self-freed heart overflowing with loving kindness and infinite bliss?

And this example should be made the ideal of every faithful Buddhist. Whatever calling he may have chosen in this life, let him be freed from ego-centric thoughts and feelings. Even when going to war for his country’s sake, let him not bear any hatred towards his enemies. In all his dealings with them let him practice the truth of non-atman. He may have to deprive his antagonist of the corporeal presence, but let him not think there are atmans, conquering each other. From a Buddhist point of view, the significance of life is not limited to the present incarnation. We must not exaggerate the significance of individuals, for they are not independent and unconditional existences. They acquire their importance and a paramount meaning, moral and religious, as soon as their fate becomes connected with the all-pervading love of the Buddha, because then they are no more particular individuals filled with egotistic thoughts and impulses, but have become love incarnate. They are so many representative types of one universal self-freed love. If they ever have to combat one another for the sake of their home and country,–which under circumstances may become unavoidable in this world of particularity,–let them forget their egotistic passions, which are the product of the atman conception of selfishness. Let them, on the contrary, be filled with the loving kindness of the Buddha; let them elevate themselves above the horizon of the mine and thine. The hand that is raised to strike and the eye that is fixed to take aim, do not belong to the individual, but are the instruments utilized by a principle higher than transient existence. Therefore, when fighting, fight with might and main, fight with your whole heart, forget your own self in the fight, and be free from all atman thought.

It is most characteristic of our religion, as we understand it, that while Buddha emphasized the paramount significance of synthetic love, he never lost sight of the indispensableness of analytical intellect. He extended his sympathy to all creatures as his own children and made no discrimination in his boundless compassion. But at the same time he was not ignorant of the fact that there were good as well as bad people, that there were innocent hearts as well as guilty ones. Not that some were more favored by the Buddha than others, but they were enabled to acquire more of the love of the Buddha. One rain falls on all kinds of plants; but they do not assimilate the water in the same fashion. Buddha’s love is universal, but our hearts, being fashioned of divergent karmas, receive it in different ways. He knows where they are finally led to, for his love is unintermittently working out their salvation, though they themselves be utterly unconscious of it.

Above all things, there is the truth, and there are many roads leading to it. It may seem at times that they collide and oppose one another. But let us rest confident that finally every ill will come to some good.

Comments

This text is taken from a larger work, entitled Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot, which sometimes appears under the alternate English title Zen for Americans. It is important to understand that the view expressed is that of a Zen Buddhist and, hence, may not apply to all Buddhists. Zen is the “religion of the Samurai.” Not surprisingly, adherents of Zen are less likely to see a conflict between war or other physical battles (including the martial arts) and Buddha’s teachings. The samurai was a warrior par excellence but, in keeping with his religion, did not allow himself to hate his enemy. Indeed, the samurai felt that any such hatred would interfere with his ability to be a great warrior.