Native American Religious and Spiritual Beliefs

By William Mackis. ©

By William Mackis. ©

It would be impossible, in this short space, to present either an acceptable overview of Native American spiritual beliefs or a reasoned defense of the importance of the study of such beliefs. Those tasks are better left to others, and the question of who those others might be, or should be, is an interesting one that I would like to take a moment to explore.

The great paradox one quickly encounters when embarking upon a study of Native American (or American Indian) spirituality is this: Those that know a good deal about the subject feel no desire to discuss it, and those desiring to discuss the subject usually know little about it.

One might go farther in exploring this paradox by explaining that the people who know a good deal about American Indian spiritual beliefs are, unsurprisingly, American Indians. Often, a component of such beliefs is secrecy, or at least privacy, which is the reason most Native American societies do not allow religious ceremonies to be photographed.

Those desiring to analyze, dissect, and discuss the subject of Native American religions are usually white people, and the subject is often approached from a comparative standpoint, all too often to the detriment of the Native American religion.

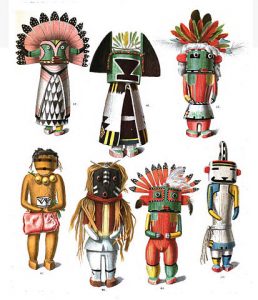

Personally, I am unsure that any spiritual belief benefits much from analysis, dissection, and open discussion among random individuals with varying personal agendas. I am sure that comparing, say, Zuni kachina dances to Methodist church services is at best unfruitful and at worst demeaning, probably to both sides.

In point of fact, it is at least a little misleading to speak of “Native American religions” at all, since spiritual beliefs varied (and still vary) widely between tribes. Cortez, arriving in Tenochtitlán in 1519, encountered Aztec practices of human sacrifice that horrified him. (Ironically, as it turned out, since he was the product of a Spanish Inquisition background that countenanced committing wholesale massacres on a scale unimaginable to his Aztec adversaries.) But when the Townsend brothers met with members of the Massapequa Tribe on Long Island in 1630, they found no such practices of human sacrifice, no temples to sun gods – nothing, in short, that seemed to resemble Aztec religious practices whatsoever. And yet, both the Aztecs and Massapequans were Native Americans, and both practiced some form of “Native American religion.”

What is my point? My point is that the study of Native American spiritual beliefs is very worthwhile, but also very difficult if one is going to attempt to do it properly. Such an endeavor has nothing to do with going to “sweat lodges” run by white persons (I’ve seen ads), or jumbled ceremonies where one smokes a Plains Indian peace pipe and beats a Navajo drum in front of a Zen altar.

My plea – a very sincere and heartfelt plea – is that the subject of Native American spirituality be approached humbly, respectfully, open-mindedly, politely, and patiently by those who are interested. If done so, the rewards can be great.

******

Of related interest: