Persecution of Quakers in Colonial New England

By John Fiske

By John Fiske

John Winthrop died in 1649 and John Cotton in 1652. Both were men of extraordinary power. Of Winthrop it is enough to say that under his skillful guidance Massachusetts had been able to pursue the daring policy which had characterized the first twenty years of her history, and which in weaker hands would almost surely have ended in disaster. Of Cotton it may be said that he was the most eminent among a group of clergymen who for learning and dialectical skill have seldom been surpassed. Neither Winthrop nor Cotton approved of toleration upon principle. Cotton, in his elaborate controversy with Roger Williams, frankly asserted that persecution is not wrong in itself; it is wicked for falsehood to persecute truth, but it is the sacred duty of truth to persecute falsehood. This was the theologian’s view. Winthrop’s was that of a man of affairs. They had come to New England, he said, in order to make a society after their own model; all who agreed with them might come and join that society; those who disagreed with them might go elsewhere; there was room enough on the American continent. But while neither Winthrop nor Cotton understood the principle of religious liberty, at the same time neither of them had the temperament which persecutes. Both were men of genial disposition, sound common-sense, and exquisite tact. Under their guidance no such tragedy would have been possible as that which was about to leave its ineffaceable stain upon the annals of Massachusetts.

It was most unfortunate that at this moment the places of these two men should have been taken by two as arrant fanatics as ever drew breath. For thirteen out of the fifteen years following Winthrop’s death, the governor of Massachusetts was John Endicott, a sturdy pioneer, whose services to the colony had been great. He was honest and conscientious, but passionate, domineering, and very deficient in tact. At the same time Cotton’s successor in position and influence was John Norton, a man of pungent wit, unyielding temper, and melancholy mood. He was possessed by a morbid fear of Satan, whose hirelings he thought were walking up and down over the earth in the visible semblance of heretics and schismatics. Under such leaders the bigotry latent in the Puritan commonwealth might easily break out in acts of deadly persecution.

The occasion was not long in coming. Already the preaching of George Fox had borne fruit, and the noble sect of Quakers was an object of scorn and loathing to all such as had not gone so far as they toward learning the true lesson of Protestantism. Of all Protestant sects the Quakers went furthest in stripping off from Christianity its non-essential features of doctrine and ceremonial. Their ideal was not a theocracy but a separation between church and state. They would abolish all distinction between clergy and laity, and could not be coaxed or bullied into paying tithes. They also refused to render military service, or to take the oath of allegiance. In these ways they came at once into antagonism both with church and with state. In doctrine their chief peculiarity was the assertion of an “Inward Light” by which every individual is to be guided in his conduct of life. They did not believe that men ceased to be divinely inspired when the apostolic ages came to an end, but held that at all times and places the human soul may be enlightened by direct communion with its Heavenly Father. Such views involved the most absolute assertion of the right of private judgment; and when it is added that in the exercise of this right many Quakers were found to reject the dogmas of original sin and the resurrection of the body, to doubt the efficacy of baptism, and to call in question the propriety of Christians turning the Lord’s Day into a Jewish Sabbath, we see that they had in some respects gone far on the road toward modern rationalism. It was not to be expected that such opinions should be treated by the Puritans in any other spirit than one of extreme abhorrence and dread. The doctrine of the “Inward Light,” or of private inspiration, was something especially hateful to the Puritan. To the modern rationalist, looking at things in the dry light of history, it may seem that this doctrine was only the Puritan’s own appeal to individual judgment, stated in different form; but the Puritan could not so regard it. To such a fanatic as Norton this inward light was but a reflection from the glare of the bottomless pit, this private inspiration was the beguiling voice of the Devil. As it led the Quakers to strange and novel conclusions, this inward light seemed to array itself in hostility to that final court of appeal for all good Protestants, the sacred text of the Bible. The Quakers were accordingly regarded as infidels who sought to deprive Protestantism of its only firm support. They were wrongly accused of blasphemy in their treatment of the Scriptures. Cotton Mather says that the Quakers were in the habit of alluding to the Bible as the Word of the Devil. Such charges, from passionate and uncritical enemies, are worthless except as they serve to explain the bitter prejudice with which the Quakers were regarded. They remind one of the silly accusation brought against Wyclif two centuries earlier, that he taught his disciples that God ought to obey the Devil; and they are not altogether unlike the assumptions of some modern theologians who take it for granted that any writer who accepts the Darwinian theory must be a materialist.

But worthless as Mather’s statements are, in describing the views of the Quakers, they are valuable as indicating the temper in which these disturbers of the Puritan theocracy were regarded. In accusing them of rejecting the Bible and making a law unto themselves, Mather simply put on record a general belief which he shared. Nor can it be doubted that the demeanor of the Quaker enthusiasts was sometimes such as to seem to warrant the belief that their anarchical doctrines entailed, as a natural consequence, disorderly and disreputable conduct. In those days all manifestations of dissent were apt to be violent, and the persecution which they encountered was likely to call forth strange and unseemly vagaries. When we remember how the Quakers, in their scorn of earthly magistrates and princes, would hoot at the governor as he walked up the street; how they used to rush into church on Sundays and interrupt the sermon with untimely remarks; how Thomas Newhouse once came into the Old South Meeting-House with a glass bottle in each hand, and, holding them up before the astonished congregation, knocked them together and smashed them, with the remark, “Thus will the Lord break you all in pieces”; how Lydia Wardwell and Deborah Wilson ran about the streets in the primitive costume of Eve before the fall, and called their conduct “testifying before the Lord”; we can hardly wonder that people should have been reminded of the wretched scenes enacted at Munster by the Anabaptists of the preceding century.

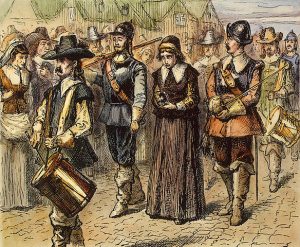

Such incidents, however, do not afford the slightest excuse for the cruel treatment which the Quakers received in Boston, nor do they go far toward explaining it. Persecution began immediately, before the new-comers had a chance to behave themselves well or ill. Their mere coming to Boston was taken as an act of invasion. It was indeed an attack upon the Puritan theocratic idea. Of all the sectaries of that age of sects, the Quakers were the most aggressive. There were at one time more than four thousand of them in English jails; yet when any of them left England, it was less to escape persecution than to preach their doctrines far and wide over the earth. Their missionaries found their way to Paris, to Vienna; even to Rome, where they testified under the very roof of the Vatican. In this dauntless spirit they came to New England to convert its inhabitants, or at any rate to establish the principle that in whatever community it might please them to stay, there they would stay in spite of judge or hangman. At first they came to Barbados, whence two of their number, Anne Austin and Mary Fisher, sailed for Boston. When they landed, on a May morning in 1656, Endicott happened to be away from Boston, but the deputy-governor, Richard Bellingham, was equal to the occasion. He arrested the two women and locked them up in jail, where, for fear they might proclaim their heresies to the crowd gathered outside, the windows were boarded up. There was no law as yet enacted against Quakers, but a council summoned for the occasion pronounced their doctrines blasphemous and devilish. The books which the poor women had with them were seized and publicly burned, and the women themselves were kept in prison half-starved for five weeks until the ship they had come in was ready to return to Barbados. Soon after their departure Endicott came home. He found fault with Bellingham’s conduct as too gentle; if he had been there he would have had the hussies flogged.

Five years afterward Mary Fisher went to Adrianople and tried to convert the Grand Turk, who treated her with grave courtesy and allowed her to prophesy unmolested. This is one of the numerous incidents that, on a superficial view of history, might be cited in support of the opinion that there has been on the whole more tolerance in the Muslim than in the Christian world. Rightly interpreted, however, the fact has no such implication. In Massachusetts the preaching of Quaker doctrines might (and did) lead to a revolution; in Turkey it was as harmless as the barking of dogs. Governor Endicott was afraid of Mary Fisher; Mahomet III. was not.

No sooner had the two women been shipped from Boston than eight other Quakers arrived from London. They were at once arrested. While they were lying in jail the Federal Commissioners, then in session at Plymouth, recommended that laws be forthwith enacted to keep these dreaded heretics out of the land. Next year they stooped so far as to seek the aid of Rhode Island, the colony which they had refused to admit into their confederacy. “They sent a letter to the authorities of that colony, signing themselves their loving friends and neighbors, and beseeching them to preserve the whole body of colonies against ‘such a pest’ by banishing and excluding all Quakers, a measure to which ‘the rule of charity did oblige them.’” Roger Williams was then president of Rhode Island, and in full accord with his noble spirit was the reply of the assembly. “We have no law amongst us whereby to punish any for only declaring by words their minds and understandings concerning the things and ways of God as to salvation and our eternal condition.” As for these Quakers we find that where they are “most of all suffered to declare themselves freely and only opposed by arguments in discourse, there they least of all desire to come.” Any breach of the civil law shall be punished, but the “freedom of different consciences shall be respected.” This reply enraged the confederated colonies, and Massachusetts, as the strongest and most overbearing, threatened to cut off the trade of Rhode Island, which forthwith appealed to Cromwell for protection. The language of the appeal is as touching as its broad Christian spirit is grand. It recognizes that by stopping trade the men of Massachusetts will injure themselves, yet, it goes on to say, “for the safeguard of their religion they may seem to neglect themselves in that respect; for what will not men do for their God?” But whatever fortune may befall, “let us not be compelled to exercise any civil power over men’s consciences.”

There could never, of course, be a doubt as to who drew up this state paper. During his last visit to England, three years before, Roger Williams had spent several weeks at Sir Harry Vane’s country house in Lincolnshire, and he had also been intimately associated with Cromwell and Milton. The views of these great men were the most advanced of that age. They were coming to understand the true principle upon which toleration should be based. Vane had said in Parliament, “Why should the labors of any be suppressed, if sober, though never so different? We now profess to seek God, we desire to see light!”

This Williams called a “heavenly speech.” The sentiment it expressed was in accordance with the practical policy of Cromwell, and in the appeal of the president of Rhode Island to the Lord Protector one hears the tone with which friend speaks to friend.

In thus protecting the Quakers, Williams never for a moment concealed his antipathy to their doctrines. The author of “George Fox digged out of his Burrowes,” the sturdy controversialist who in his seventy-third year rowed himself in a boat the whole length of Narragansett bay to engage in a theological tournament against three Quaker champions, was animated by nothing less than the broadest liberalism in his bold reply to the Federal Commissioners in 1657. The event showed that under his guidance the policy of Rhode Island was not only honorable but wise. The four confederated colonies all proceeded to pass laws banishing Quakers and making it a penal offence for shipmasters to bring them to New England. These laws differed in severity. Those of Connecticut, in which we may trace the influence of the younger John Winthrop, were the mildest; those of Massachusetts were the most severe, and as Quakers kept coming all the more in spite of them, they grew harsher and harsher. At first the Quaker who persisted in returning was to be flogged and imprisoned at hard labor, next his ears were to be cut off, and for a third offence his tongue was to be bored with a hot iron. At length in 1658, the Federal Commissioners, sitting at Boston with Endicott as chairman, recommended capital punishment. It must be borne in mind that the general reluctance toward prescribing or inflicting the death penalty was much weaker then than now. On the statute-books there were not less than fifteen capital crimes, including such offences as idolatry, witchcraft, blasphemy, marriage within the Levitical degrees, “presumptuous sabbath-breaking,” and cursing or smiting one’s parents. The infliction of the penalty, however, lay practically very much within the discretion of the court, and was generally avoided except in cases of murder or other heinous felony. In some of these ecclesiastical offences the statute seems to have served the purpose of a threat, and was therefore perhaps the more easily enacted. Yet none of the colonies except Massachusetts now adopted the suggestion of the Federal Commissioners and threatened the Quakers with death.

In Massachusetts the opposition was very strong indeed, and its character shows how wide the divergence in sentiment had already become between the upper stratum of society and the people in general. This divergence was one result of the excessive weight given to the clergy by the restriction of the suffrage to church members. One might almost say that it was not the people of Massachusetts, after all, that shed the blood of the Quakers; it was Endicott and the clergy. The bill establishing death as the penalty for returning after banishment was passed in the upper house without serious difficulty; but in the lower house it was at first defeated. Of the twenty-six deputies fifteen were opposed to it, but one of these fell sick and two were intimidated, so that finally the infamous measure was passed by a vote of thirteen against twelve. Probably it would not have passed but for a hopeful feeling that an occasion for putting it into execution would not be likely to arise. It was hoped that the mere threat would prove effective. Endicott begged the Quakers to keep away, saying earnestly that he did not desire their death; but the more resolute spirits were not deterred by fear of the gallows. In September, 1659, William Robinson, Marmaduke Stevenson, and Mary Dyer, who had come to Boston expressly to defy the cruel law, were banished. Mrs. Dyer was a lady of good family, wife of the secretary of Rhode Island. She had been an intimate friend of Mrs. Hutchinson. While she went home to her husband, Stevenson and Robinson went only to Salem and then faced about and came back to Boston. Mrs. Dyer also returned. All three felt themselves under divine command to resist and defy the persecutors. On the 27th of October they were led to the gallows on Boston Common, under escort of a hundred soldiers. Many people had begun to cry shame on such proceedings, and it was thought necessary to take precautions against a tumult. The victims tried to address the crowd, but their voices were drowned by the beating of drums. While the Rev. John Wilson railed and scoffed at them from the foot of the gallows the two brave men were hanged. The halter had been placed upon Mrs. Dyer when her son, who had come in all haste from Rhode Island, obtained her reprieve on his promise to take her away. The bodies of the two men were denied Christian burial and thrown uncovered into a pit. All the efforts of husband and son were unable to keep Mrs. Dyer at home. In the following spring she returned to Boston and on the first day of June was again taken to the gallows. At the last moment she was offered freedom if she would only promise to go away and stay, but she refused. “In obedience to the will of the Lord I came,” said she, “and in his will I abide faithful unto death.” And so she died.

Public sentiment in Boston was now turning so strongly against the magistrates that they began to weaken in their purpose. But there was one more victim. In November, 1660, William Leddra returned from banishment. The case was clear enough, but he was kept in prison four months and every effort was made to induce him to promise to leave the colony, but in vain. In the following March he too was put to death. A few days before the execution, as Leddra was being questioned in court, a memorable scene occurred. Wenlock Christison was one of those who had been banished under penalty of death. On his return he made straight for the town-house, strode into the court-room, and with uplifted finger addressed the judges in words of authority. “I am come here to warn you,” said he, “that ye shed no more innocent blood.” He was instantly seized and dragged off to jail. After three months he was brought to trial before the Court of Assistants. The magistrates debated for more than a fortnight as to what should be done. The air was thick with mutterings of insurrection, and they had lost all heart for their dreadful work. Not so the savage old man who presided, frowning gloomily under his black skull cap. Losing his patience at last, Endicott smote the table with fury, upbraided the judges for their weakness, and declared himself so disgusted that he was ready to go back to England. “You that will not consent, record it,” he shouted, as the question was again put to vote, “I thank God I am not afraid to give judgment.” Christison was condemned to death, but the sentence was never executed. In the interval the legislature assembled, and the law was modified. The martyrs had not died in vain. Their cause was victorious. A revolution had been effected. The Puritan ideal of a commonwealth composed of a united body of believers was broken down, never again to be restored. The principle had been admitted that the heretic might come to Massachusetts and stay there.

It was not in a moment, however, that these results were fully realized. For some years longer Quakers were fined, imprisoned, and now and then tied to the cart’s tail and whipped from one town to another. But these acts of persecution came to be more and more discountenanced by public opinion until at length they ceased.

It was on the 25th of May, 1660, just one week before the martyrdom of Mary Dyer, that Charles II. returned to England to occupy his father’s throne. One of the first papers laid before him was a memorial in behalf of the oppressed Quakers in New England. In the course of the following year he sent a letter to Endicott and the other New England governors, ordering them to suspend proceedings against the Quakers, and if any were then in prison, to send them to England for trial. Christison’s victory had already been won, but the “King’s Missive” was now partially obeyed by the release of all prisoners. As for sending anybody to England for trial, that was something that no New England government could ever be made to allow.

Charles’s defense of the Quakers was due, neither to liberality of disposition nor to any sympathy with them, but rather to his inclinations toward Romanism. Unlike in other respects, Quakers and Catholics were alike in this, that they were the only sects which the Protestant world in general agreed in excluding from toleration. Charles wished to secure toleration for Catholics, and he could not prudently take steps toward this end without pursuing a policy broad enough to diminish persecution in other directions, and from these circumstances the Quakers profited. At times there was something almost like a political alliance between Quaker and Catholic, as instanced in the relations between William Penn and Charles’s brother, the Duke of York.

Besides all this, Charles had good reason to feel that the governments of New England were assuming too many airs of sovereignty. There were plenty of people at hand to work upon his mind. The friends of Gorton and Child and Vassall were loud with their complaints. Samuel Maverick swore that the people of New England were all rebels, and he could prove it. The king was assured that the Confederacy was “a war combination, made by the four colonies when they had a design to throw off their dependence on England, and for that purpose.” The enemies of the New England people, while dilating upon the rebellious disposition of Massachusetts, could also remind the king that for several years that colony had been coining and circulating shillings and sixpences with the name “Massachusetts” and a tree on one side, and the name “New England” with the date on the other. There was no recognition of England upon this coinage, which was begun in 1652 and kept up for more than thirty years. Such pieces of money used to be called “pine-tree shillings”; but, so far as looks go, the tree might be anything, and an adroit friend of New England once gravely assured the king that it was meant for the royal oak in which his majesty hid himself after the battle of Worcester!

Against the colony of New Haven the king had a special grudge. Two of the regicide judges, who had sat in the tribunal which condemned his father, escaped to New England in 1660 and were well received there. They were gentlemen of high position. Edward Whalley was a cousin of Cromwell and Hampden. He had distinguished himself at Naseby and Dunbar, and had risen to the rank of lieutenant-general. He had commanded at the capture of Worcester, where it is interesting to observe that the royalist commander who surrendered to him was Sir Henry Washington, own cousin to the grandfather of George Washington. The other regicide, William Goffe, as a major-general in Cromwell’s army, had won such distinction that there were some who pointed to him as the proper person to succeed the Lord Protector on the death of the latter. He had married Whalley’s daughter. Soon after the arrival of these gentlemen, a royal order for their arrest was sent to Boston. If they had been arrested and sent back to England, their severed heads would soon have been placed over Temple Bar. The king’s detectives hotly pursued them through the woodland paths of New England, and they would soon have been taken but for the aid they got from the people. Many are the stories of their hairbreadth escapes. Sometimes they took refuge in a cave on a mountain near New Haven, sometimes they hid in friendly cellars; and once, being hard put to it, they skulked under a wooden bridge, while their pursuers on horseback galloped by overhead. After lurking about New Haven and Milford for two or three years, on hearing of the expected arrival of Colonel Nichols and his commission, they sought a more secluded hiding-place near Hadley, a village lately settled far up the Connecticut river, within the jurisdiction of Massachusetts. Here the avengers lost the trail, the pursuit was abandoned, and the weary regicides were presently forgotten.

The people of New Haven had been especially zealous in shielding the fugitives. Mr. Davenport had not only harbored them in his own house, but on the Sabbath before their expected arrival he had preached a very bold sermon, openly advising his people to aid and comfort them as far as possible. The colony, moreover, did not officially recognize the restoration of Charles II. to the throne until that event had been commonly known in New England for more than a year. For these reasons the wrath of the king was specially roused against New Haven, when circumstances combined to enable him at once to punish this disloyal colony and deal a blow at the Confederacy. We have seen that in restricting the suffrage to church members New Haven had followed the example of Massachusetts, but Connecticut had not; and at this time there was warm controversy between the two younger colonies as to the wisdom Of such a policy. As yet none of the colonies save Massachusetts had obtained a charter, and Connecticut was naturally anxious to obtain one. Whether through a complaisant spirit connected with this desire, or through mere accident, Connecticut had been prompt in acknowledging the restoration of Charles II.; and in August, 1661, she dispatched the younger Winthrop to England to apply for a charter. Winthrop was a man of winning address and of wide culture. His scientific tastes were a passport to the favor of the king at a time when the Royal Society was being founded, of which Winthrop himself was soon chosen a fellow. In every way the occasion was an auspicious one. The king looked upon the rise of the New England Confederacy with unfriendly eyes. Massachusetts was as yet the only member of the league that was really troublesome; and there seemed to be no easier way to weaken her than to raise up a rival power by her side, and extend to it such privileges as might awaken her jealousy. All the more would such a policy be likely to succeed if accompanied by measures of which Massachusetts must necessarily disapprove, and the suppression of New Haven would be such a measure.

In accordance with these views, a charter of great liberality was at once granted to Connecticut, and by the same instrument the colony of New Haven was deprived of its separate existence and annexed to its stronger neighbor. As if to emphasize the motives which had led to this display of royal favor toward Connecticut, an equally liberal charter was granted to Rhode Island. In the summer of 1664 Charles II. sent a couple of ships-of-war to Boston harbor, with 400 troops under command of Colonel Richard Nichols, who had been appointed, along with Samuel Maverick and two others as royal commissioners, to look after the affairs of the New World. Colonel Nichols took his ships to New Amsterdam, and captured that important town. After his return the commissioners held meetings at Boston, and for a time the Massachusetts charter seemed in danger. But the Puritan magistrates were shrewd, and months were frittered away to no purpose. Presently the Dutch made war upon England, and the king felt it to be unwise to irritate the people of Massachusetts beyond endurance. The turbulent state of English politics which followed still further absorbed his attention, and New England had another respite of several years.

In New Haven a party had grown up which was dissatisfied with its extreme theocratic policy and approved of the union with Connecticut. Davenport and his followers, the founders of the colony, were beyond measure disgusted. They spurned “the Christless rule” of the sister colony. Many of them took advantage of the recent conquest of New Netherland, and a strong party, led by the Rev. Abraham Pierson, of Branford, migrated to the banks of the Passaic in June, 1667, and laid the foundations of Newark. For some years to come the theocratic idea that had given birth to New Haven continued to live on in New Jersey. As for Mr. Davenport, he went to Boston and ended his days there. Cotton Mather, writing at a later date, when the theocratic scheme of the early settlers had been manifestly outgrown and superseded, says of Davenport:

“Yet, after all, the Lord gave him to see that in this world a Church-State was impossible, whereinto there enters nothing which defiles.”

The theocratic policy, alike in New Haven and in Massachusetts, broke down largely through its inherent weakness. It divided the community, and created among the people a party adverse to its arrogance and exclusiveness. This state of things facilitated the suppression of New Haven by royal edict, and it made possible the victory of Wenlock Christison in Massachusetts. We can now see the fundamental explanation of the deadly hostility with which Endicott and his party regarded the Quakers. The latter aimed a fatal blow at the very root of the idea which had brought the Puritans to New England. Once admit these heretics as citizens, or even as tolerated sojourners, and there was an end of the theocratic state consisting of a united body of believers. It was a life-and-death struggle, in which no quarter was given; and the Quakers, aided by popular discontent with the theocracy, even more than by the intervention of the crown, won a decisive victory.