Religious Orders and the Counter-Reformation

[This is taken from History of the Catholic Church.]

[This is taken from History of the Catholic Church.]

The religious orders, like most other institutions of the age preceding the Reformation, stood badly in need of reorganization and reform. Various causes had combined to bring about a relaxation of the discipline prescribed by their holy founders, and to introduce a spirit of worldliness, that boded ill both for the individual members as well as for the success of the work for which these orders had been established. The interference of outside authorities lay or ecclesiastical in the appointment of superiors, the union of several houses under one superior, the accumulation of wealth, the habitual neglect of the superiors to make their visitations, and a general carelessness in the selection and training of the candidates to be admitted into the various institutions, were productive of disastrous results. It is difficult, however, to arrive at a correct estimate as to the extent of the evil, because the condition of affairs varied very much in the different religious orders and in the different provinces and houses of the same order. At all times a large proportion of the religious of both sexes recognized and deplored the spirit of laxity that had crept in, and labored strenuously for a return to the old ideals long before the Lutheran campaign had made it necessary to choose between reform and suppression.

The Benedictines, who had done excellent work for the promotion of the spiritual and temporal welfare of the people amongst whom they labored, suffered more than any other body from the interference of lay patrons in the appointment of abbots, as well as from the want of any central authority capable of controlling individual houses and of insisting upon the observance of the rules and constitution. Various efforts were made, however, to introduce reforms during the sixteenth century. In France the most important of these reforms was that begun in the abbey of St. Vannes by the abbot, Didier de la Cour. Recognizing the sad condition of affairs he labored incessantly to bring about a return to the strict rule of St. Benedict. His efforts were approved by Clement VIII. in 1604. Many houses in France having accepted the reform, it was resolved to unite them into one congregation under the patronage of St. Maur, the disciple of St. Benedict. The new congregation of St. Maur was sanctioned by Louis XIII. and by Pope Gregory XV. (1621). The Maurists devoted themselves to the study of the sacred sciences, more especially to history, liturgy and patrology, and set an example of thorough scholarship which won for them the praise of both friends and foes. The names of D’Achery, Mabillon, Ruinart, Martene, Thierry, Lami and Bouquet are not likely to be forgotten so long as such works as the Amplissima Collectio Veterum Scriptorum, Thesaurus Anecdotorum, Gallia Christiana, Histoire Litteraire de la France, De Re Diplomatica, L’Art de verifier les dates, the Receuil des historiens des Gaules, etc., survive to testify to the labors and research of the Congregation of St. Maur.

The reform movement among the Dominicans had made itself manifest from the days of Raymond of Capua (1390), who ordered that in every province there should be at least one house where the rule of St. Dominic might be observed in its original strictness. The success of the reform varied in the different countries and even in the different houses of the same province, but in the sixteenth century the general tendency was undoubtedly upwards. The religious rebellion inflicted serious losses on the order and led to the almost complete extinction of provinces that once were flourishing; but the Spanish and Portuguese discoveries in America and the spread of the missionary movement opened up for the order new fields, where its members were destined to do lasting service to religion and to win back in the New World more than they had lost in the Old. Discipline among the Cistercians, too, had become relaxed, but a general improvement set in which led to the formation of new congregations, the principal of which were the Congregation of the Feuillants approved by Sixtus V (1587), and of the Trappists, which take their name from the monastery of La Trappe and owe their origin to the zealous efforts of the Abbot de Rance (1626-1700).

The Franciscans were divided already into the Observants and the Conventuals, but even among the Observants the deteriorating influence of the age had made itself felt. Matteo di Bassi set himself in the convent of Monte Falco to procure a complete return to the original rule of St. Francis, and proceeded to Rome to secure the approbation of Clement VII. In 1528 by the Bull, Religionis Zelus the Pope permitted himself and his followers to separate from the Observants, to wear the hood (cappuccio, hence the name Capuchins) which Matteo claimed to have been the dress of St. Francis, to wear the beard, to found separate houses in Italy, and to preach to the people. Soon the Capuchins spread through Italy, and so popular did they become that Gregory XIII. withdrew the regulations by which they were forbidden to found separate houses outside of Italy. The new order suffered many trials more especially after the apostasy of its vicar-general Ochino in 1544, but with the blessing of God these difficulties were overcome. The Capuchins rendered invaluable service to religion by their simple straightforward style of preaching so opposed as it was to the literary musings that passed for sermons at the time, by their familiar intercourse with the poor whom they assisted in both spiritual and temporal misfortunes, by their unswerving loyalty to the Pope and by the work they accomplished on the foreign missions, more especially in those lands which had once been the glory of the Church but where religion had been extinguished almost completely by the domination of the Saracen.

The revival was not confined, however, merely to a reform of the older religious orders. The world had changed considerably since the constitutions of these bodies had been formulated by their holy founders. New conditions and new dangers necessitated the employment of new weapons and new methods for the defense of religion. Fortunately a band of zealous men were raised up by God to grapple with the problems of the age, and to lay the foundation of religious societies, many of which were destined to confer benefits on religion hardly less permanent and less valuable than had been conferred in other times by such distinguished servants of God as St. Benedict, St. Dominic, and St. Francis of Assisi.

The Theatines, so called from Chieti (Theate) the diocese of Peter Caraffa, had their origin in a little confraternity founded by Gaetano di Tiene a Venetian, who gathered around him a few disciples, all of them like himself zealous for the spiritual improvement of both clergy and people (1524). During a visit to Rome Gaetano succeeded in eliciting the sympathy of Peter Caraffa (then bishop of Theate and afterwards cardinal and Pope) and in inducing him to become the first superior of the community. The institution was approved by Clement VII. in 1524. Its founders aimed at introducing a higher standard of spiritual life amongst both clergy and laity by means of preaching and by the establishment of charitable institutions. The order spread rapidly in Italy, where it did much to save the people from the influence of Lutheranism, in Spain were it was assisted by Philip II., in France where Cardinal Mazarin acted as its patron, and in the foreign missions, especially in several parts of Asia, the Theatines won many souls to God.

The Regular Clerics of St. Paul, better known as the Barnabites from their connection with the church of St. Barnabas at Milan, were founded by Antony Maria Zaccaria of Cremona, Bartholomew Ferrari and Jacopo Morigia. Shocked by the low state of morals then prevalent in so many Italian cities, these holy men gathered around them a body of zealous young priests, who aimed at inducing the people by means of sermons and instructions to take advantage of the sacrament of Penance. The order was approved by Clement VII. in 1533, and received many important privileges from his successors. Its members worked in complete harmony with the secular clergy and in obedience to the commands of the bishops. They bound themselves not to seek or accept any preferment or dignity unless at the express direction of the Pope. In Milan they were beloved by St. Charles Borromeo who availed himself freely of their services, and they were invited to Annecy by St. Francis de Sales. Several houses of the Barnabites were established in Italy, France, and Austria. In addition to their work of preaching and instructing the people they established many flourishing colleges, and at the request of the Pope undertook charge of some of the foreign missions.

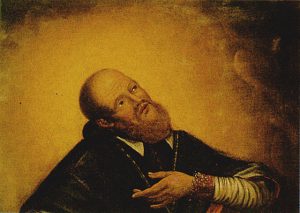

The founder of the Oblates was St. Charles Borromeo (1538-84) who was created cardinal by his uncle Pius IV., at the age of twenty-three, and who during his comparatively short life did more for the reform of the Church and for the overthrow of Protestantism than any individual of his age. It was due mainly to his exertions that the Council of Trent was re-convoked, and to his prudent advice that it was carried to a successful conclusion. Once the decrees of the Council had received the approval of the Pope St. Charles spared no pains to see that they were put into execution not only in his own diocese of Milan but throughout the entire Church. For a long time personal government of his diocese was impossible as his presence in Rome was insisted upon by the Pope; but as soon as he could secure permission he hastened to Milan, where he repressed abuses with a stern hand, introduced regular diocesan and provincial synods, visited in person the most distant parts of the diocese, won back thousands who had gone over to heresy in the valleys of Switzerland, and defended vigorously the rights and the liberties of the Church against the Spanish representatives. In all his reforms he was supported loyally by the religious orders, more especially by the Jesuits and the Barnabites, with whom he maintained at all times the most friendly relations. At the same time he felt the need of a community of secular priests, who while remaining under the authority of the bishop would set an example of clerical perfection, and who would be ready at the request of the bishop to volunteer for the work that was deemed most pressing. he was particularly anxious that such a body should undertake the direction of the diocesan seminary, and should endeavor to send forth well educated and holy priests. With these objects in view he established the Oblates in 1578, and the community fully justified his highest expectations.

The Oratorians were established by St. Philip Neri (1515-95) the reformer and one of the patrons of Rome. He was a native of Florence, who when still a young man turned his back upon a promising career in the world in order to devote himself entirely to the service of God. Before his ordination he labored for fifteen years visiting the sick in the hospitals, assisting the poorer pilgrims, and instructing the young. He formed a special confraternity, and gathered around him a body of disciples both cleric and lay. After his ordination they were accustomed to hold their conferences in a little room (Oratorium, Oratory) over the church of St. Girolmao. Here sermons and instructions were given on all kinds of subjects, particularly on the Sacred Scriptures, the writings of the Fathers, and the leading events in the history of the Church. The society was approved by Gregory XIII. (1575) under the title of the Congregation of the Oratory. It was to be composed of secular priests living together under a rule, but bound by no special vows. St. Philip Neri was convinced that the style of preaching in vogue at the time was responsible in great measure for the decline of religion and morality. Being a man of sound education himself he insisted that his companions should devote themselves to some particular department of ecclesiastical knowledge, and should give the people the fruits of their study. Baronius, for example, the author of the celebrated Annales Ecclesiastici, is said to have preached for thirty years on the history of the Church. In this way St. Philip provided both for sound scholarship and useful instruction. Many branches of the Oratory were founded in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in South America.

Recognizing the need for an improvement in the education and lives of the French clergy and mindful of the benefits conferred on Rome by the community of St. Philip Neri, the Abbe, afterwards Cardinal, Pierre de Berulle determined to found an Oratory in Paris. The Paris Oratorians were a community of secular priests bound by no special vows, but living under a common rule with the object of fulfilling as perfectly as possible the obligations they had undertaken at their ordination. The project received the warm support of Cardinal Richelieu and was approved by Paul V. in 1613. At the time clerical education in Paris and throughout France was in a condition of almost hopeless confusion. The French Oratorians, devoted as they were themselves to study, determined to organize seminaries on the plan laid down by the Council of Trent, and to take charge of the administration of such institutions. In philosophy the Oratory produced scholars such as Malebranche, in theology Thomassin and Morin, in Scripture Houbigant and Richard Simon, and in sacred eloquence such distinguished preachers as Lajeune and Massillon. The Oratorians survived the stormy days of the Jansenist struggle though the peace of the community was disturbed at times by the action of a few of its members, but it went down before the wild onslaught of the Revolution. It was revived, however, by Pere Gratry in 1852.

The Brothers of Charity were founded by a Portuguese, who having been converted by a sermon of St. John d’Avila, devoted himself to the relief of human suffering in every form. On account of his great charity and zeal for souls he received the surname, St. John of God. He gathered around him a band of companions who assisted him in caring for the sick in the hospital he had founded at Granada. After his death in 1550 the work that he had begun was carried on by his disciples, whose constitutions were approved by Pius V. in 1572. Soon through the generosity of Philip II. and of the Spanish nobles hospitals were established in various cities of Spain, and placed under the control of the Brothers of St. John of God. They were invited by the Pope to open a house in Rome, and they went also to Paris on the invitation of the queen (1601). At the time of the French Revolution they had charge of forty hospitals, from all of which they were expelled. The founder was canonized in 1690, and named as patron of hospitals by Leo XIII. in 1898.

The Piarists or Patres Piarum Scholarum were founded by St. Joseph Calazansa (1556-1648), who had been vicar-general of the diocese of Urgel in Spain, an office which he resigned in order to betake himself to Rome. Here he began to gather the poorer children for instruction, and as the teachers were unwilling to assist him unless they were given extra remuneration, he opened a free school in Rome in 1597. The school was taught by himself and two or three priests whom he had interested in the work. From these unpretentious beginnings sprang the society of the Fathers of the Pious Schools. The object of the society, which was composed of priests, was the education of the young both in primary and secondary schools. The society was approved by Paul V., and established finally as a recognized institution by Gregory XV. (1621). It spread rapidly into Italy, Austria, and Poland. Somewhat akin to the Piarists were the Fathers of Christian Doctrine, founded by Caesar de Bus for the purpose of educating the young. The society was composed of priests, and received the approval of Clement VIII. in 1597. Later on it united with the Somaschans, who had been established by St. Jerome Aemilian with a similar purpose, but on account of certain disputes that arose the two bodies were separated in 1647.

The Brothers of the Christian Schools were founded by John Baptist de la Salle (1651-1719). The founder was a young priest of great ability, who had read a distinguished course in arts and theology before his ordination. Having been called upon to assist in conducting a free school opened at Rheims in 1679 he threw himself into the work with vigor, devoting nearly all his energies to the instruction of the teachers. These he used to gather around him after school hours to encourage them to their work, to suggest to them better methods of imparting knowledge and generally to correct any defects that he might have noticed during the course of his daily visits to the schools. In this way he brought together a body of young men interested in the education of the children of the poor, from which body were developed the Brothers of the Christian Schools. At first he intended that some of the congregation should be priests, but later on he changed his mind, and made it a rule that none of the Brothers should become priests, nor should any priest be accepted as a novice. For a long time the holy founder was engaged in an uphill struggle during which the very existence of the institute was imperiled. Distrusted by some of the ecclesiastical authorities, attacked by enemies on all side, deserted by a few of his own most trusted disciples, a man of less zeal and determination would have abandoned the project in despair. But de la Salle was not discouraged. He composed a constitution for his followers, and in 1717 he held a general chapter, in which he secured the election of a superior-general. From this time the Institute of Christian Brothers progressed by leaps and bounds. The holy founder of the society was a pioneer in the work of primary education. In teaching, in the grading of the pupils, and in constructing and furnishing the schools new methods were followed; more liberty was given in the selection of programmes to suit the districts in which schools were opened; normal schools were established to train the young teachers for their duties, and care was taken that religious and secular education should go forward hand in hand. The society spread rapidly in France, more especially after it had received the approval of Louis XV., and had been recognized as a religious congregation by Benedict XIII. (1725). During the Revolution the society was suppressed, and the Brothers of the Christian Schools suffered much rather than prove disloyal to the Pope. In 1803 the institute was re- rganized, and since that time houses have been opened in nearly every part of the world. John Baptist de la Salle was canonized by Leo XIII. in 1900.

The Congregation of the Priests of the Mission, better known as Lazarists from the priory of St. Lazare which they occupied in Paris, and as Vincentians from the name of their founder, St. Vincent de Paul, was established in 1624. St. Vincent was born at Pouy in Gascony in 1576, received his early education at a Franciscan school, and completed his theological studies at the University of Toulouse, where he was ordained in 1600. Four years later the ship on which he journeyed from Marseilles having been attacked by Barbary pirates, he was taken prisoner and brought to Tunis, where he was sold as a slave. He succeeded in making his escape from captivity (1607) by converting his master, a Frenchman who had deserted his country and his religion. He went to Rome, from which he was dispatched on a mission to the French Court, and was appointed almoner to queen Margaret of Valois. Later on he became tutor to the family of the Count de Gondi, the master of the French galleys. During his stay there St. Vincent found time to preach to the peasants on the estate of his employer, and to visit the prisoners condemned to the galleys. The splendid results of his labors among these classes bore such striking testimony to the success of his missions that St. Vincent was induced to found a congregation of clergymen for this special work. Something of this kind was required urgently in France at this period. The absence of seminaries and the want of any properly organized system of clerical education had produced their natural consequences on the clergy. In the country districts particularly, the priests had neither the knowledge nor the training that would enable them to discharge their sacred functions. From this it followed that the people were not instructed, and the sacraments were neglected.

By opening a house in Paris in 1624 St. Vincent took the first practical step towards the foundation of a religious congregation, that was destined to renew and to strengthen religion in France. Later on the society received the sanction of the Archbishop of Paris, and of Louis XIII., and finally it was approved by Urban VIII. in the Bull, Salvatoris Nostri, dated 12th January 1632. In the same year St. Vincent took possession of the priory of St. Lazare placed at his disposal by the canons regular of St. Victor. The Congregation of the Mission was to be a congregation of secular clergymen, bound by simple religious vows. Its principal work, besides the sanctification of its own members, was to give missions to the poor particularly in country districts, and to promote a high standard of clerical life. The bishops of France were delighted with the programme of the new congregation. Invitations poured in from all sides on the disciples of St. Vincent asking them to undertake missions, and wherever they went their labors were attended with success. As a rule St. Vincent established a confraternity of charity in the parishes that he visited to help the poor and above all to look after the homeless orphans.

It was not long until he discovered that, however successful his missions might be, they could effect little permanent good unless the priests in charge of the parishes were determined to continue the work that had been begun, and to reap the harvest which the missioners had planted. At that time there were no seminaries in France, so that candidates for the priesthood were ordained on the completion of their university course without any special training for their sacred office. At the request of some of the bishops St. Vincent determined to give retreats to those who were preparing for Holy Orders. At first these retreats lasted only ten days, but they were productive of such splendid results that they were extended to several months. Finally they led to the establishment of clerical seminaries, of which institutions St. Vincent and his associates took charge in several of the dioceses of France. Before his death they had control of eleven French seminaries; and at the time of the Revolution fully one-third of the diocesan seminaries were in the hands of his disciples. By means of retreats for the clergy, and spiritual conferences organized for their improvement St. Vincent kept in close touch with those whom he had trained, and afforded them an opportunity of renewing their fervor and completing their education.

It was fortunate for France that God had raised up a man so prudent and zealous as St. Vincent to be a guide to both priests and people during the difficult times through which the country was then passing. From without, danger threatened the Church on the side of the Huguenot heretics, and from within, Jansenism and Gallicanism bade fair to captivate the sympathy of both clergy and people. At first St. Vincent was on friendly terms with the Abbot de St. Cyran, the leader of the Jansenists in France, but once he realized the dangerous nature of his opinions and the errors contained in such publications as the Augustus of Jansen and the Frequent Communion of Arnauld he threw himself vigorously into the campaign against Jansenism. At court, in his conferences with bishops and priests, in university circles, and in the seminaries he exposed the insidious character of its tenets. At Rome he urged the authorities to have recourse to stern measures, and in France he strove hard to procure acceptance of the Roman decisions. And yet in all his work against the Jansenists there was nothing of the bitterness of the controversialist. He could strike hard when he wished, but he never forgot that charity is a much more effective weapon than violence. In his own person he set the example of complete submission to the authority of the Pope, and enjoined such submission on his successors. St. Vincent died in 1660. His loss was mourned not merely by his own spiritual children, the Congregation of the Mission and the Sisters of Charity, but by the poor of Paris and of France to whom he was a generous benefactor, as well as by the bishops and clergy to whom he had been a friend and a guide. To his influence more than to any other cause is due the preservation of France to the Church in the seventeenth century.

But the work of the Congregation of the Mission was not confined to France. Its disciples spread into Italy, Spain, Portugal, Poland, Ireland, and England. They went as missionaries to Northern Africa to labor among the Barbary pirates by whom St. Vincent had been captured, to Madagascar, to some of the Portuguese colonies in the East, to China, and to the territories of the Sultan. At the Revolution most of their houses in France were destroyed, and many of the Vincentians suffered martyrdom. When the worst storms, however, had passed the congregation was re-established in France, and its members labored earnestly in the spirit of its holy founder to recover much of what had been lost.

The founder of the Sulpicians was Jean Jacques Olier (1608-57) the friend and disciple of St. Vincent de Paul. Impressed with the importance of securing a good education and training for the clergy, he and a couple of companions retired to a house in Vaugirard (1641), where they were joined by a few seminarists, who desired to place themselves under his direction. Later on he was offered the parish of St. Sulpice, then one of the worst parishes in Paris from the point of view of religion and morality. The little community of priests working under the rules compiled by Olier for their guidance soon changed completely the face of the entire district. House to house visitations were introduced; sermons suitable to the needs of the people were given; catechism classes were established, and in a very short time St. Sulpice became the model parish of the capital.

In 1642 a little seminary was opened and rules were drawn up for the direction of the students, most of whom attended the theological lectures at the Sorbonne. Priests and students formed one community, and as far as possible followed the same daily routine. During their free time the students assisted in the work of the parish by visiting the sick and taking charge of classes for catechism. At first Olier had no intention of founding seminaries throughout France. His aim was rather to make St. Sulpice a national seminary, from which young priests might go forth properly equipped, and qualified to found diocesan institutions on similar lines if their superiors favored such an undertaking. But yielding to the earnest solicitations of several of the bishops he opened seminaries in several parts of France, and entrusted their administration to members of his own community. The first of these was founded at Nantes in 1648. During the lifetime of the founder a few of the Sulpicians were dispatched to Canada, where they established themselves at Montreal, and labored zealously for the conversion of the natives. Like St. Vincent, the founder of the Sulpicians worked incessantly against Jansenism, and impressed upon his followers the duty of prompt obedience to the bishops and to the Pope, lessons which they seem never to have forgotten. The Sulpicians according to their constitution are a community of secular priests bound by no special religious vows.

The religious order, however, that did most to stem the advancing tide of heresy and to raise the drooping spirits of the Catholic body during the saddest days of the sixteenth century was undoubtedly the Society of Jesus, founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola. By birth St. Ignatius was a Spaniard, and by profession he was a soldier. Having been wounded at the siege of Pampeluna in 1521 he turned his mind during the period of his convalescence to the study of spiritual books, more particularly the Lives of the Saints. As he read of the struggles some of these men had sustained and of the victories they had achieved he realized that martial fame was but a shadow in comparison with the glory of the saints, and he determined to desert the army of Spain to enroll himself among the servants of Christ. With the overthrow of the Moorish kingdom of Granada fresh in his mind, it is not strange that he should have dreamt of the still greater triumph that might be secured by attacking the Mohammedans in the very seat of their power, and by inducing them to abandon the law of the Prophet for the Gospel of the Christians. With the intention of preparing himself for this work he bade good-bye to his friends and the associations of his youth, and betook himself to a lonely retreat at Manresa near Montserrat, where he gave himself up to meditation and prayer under the direction of a Benedictine monk. The result of his stay at Manresa and of his communings with God are to be seen in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, a work which in the hands of his disciples has done wonders for the conversion and perfection of souls, and which in the opinion of those competent to judge has no serious rivals except the Bible and the Imitation of Christ. From Manresa he journeyed to the Holy Land to visit its sacred shrines, and to labor for the conversion of the Infidel conquerors, but having found it impossible to undertake this work at the time he returned to Europe.

Realizing that his defective education was a serious obstacle to the establishment of the religious order that he contemplated, he went to work with a will to acquire the rudiments of grammar. When this had been accomplished successfully he pursued his higher studies at Alcala, Salamanca, and Paris, where he graduated as a doctor in 1534. But while earnest in the pursuit of knowledge he never forgot that knowledge was but a means of preparing himself for the accomplishment of the mission to which God had called him. While at Paris he gathered around him a group of students, Francis Xavier, Lainez, Salmeron, Bodadilla, Rodriguez and Faber, with which body Lejay, Codure and Broet were associated at a later period. On the feast of the Assumption (1534) Ignatius and his companions wended their way to the summit of Montmartre overlooking the city of Paris, where having received Holy Communion they pledged themselves to labor in the Holy Land. Having discovered that this project was almost impossible they determined to place themselves at the disposal of the Pope. In Rome Ignatius explained the objects and rules of the proposed society to Paul III. and his advisers. In September 1540 the approval of the Pope was obtained though with certain restrictions, which were abolished in 1543, and in the following year Ignatius was elected first general of the Society of Jesus.

St. Ignatius had the greatest respect for the older religious orders, the Benedictines, the Dominicans, and the Franciscans, to all of which he was deeply indebted; but he believed that the new conditions under which his followers would be called upon to do battle for Christ necessitated new rules and a new constitution. The Society of Jesus was not to be a contemplative order seeking only the salvation of its own members. Its energies were not to be confined to any particular channel. No extraordinary fasts or austerities were imposed, nor was the solemn chanting of the office or the use of a particular dress insisted upon. The society was to work “for the greater glory of God” in whatever way the circumstances demanded. On one thing only did St. Ignatius lay peculiar emphasis, and that was the absolute necessity of obedience to superiors in all things lawful, and above all of obedience to the Pope. The wisdom of this injunction is evident enough at all times, but particularly in an age when religious authority, even that of the successor of St. Peter, was being called in question by so many. Members of the society were forbidden to seek or accept any ecclesiastical dignities or preferments.

The constitution of the Society of Jesus was not drawn up with undue haste. St. Ignatius laid down rules for his followers, but it was only when the value of these regulations had been tested by practice that he embodied them in the constitution, endorsed by the first general congregation held in 1558. According to the constitution complete administrative authority is vested in the general, who is elected by a general congregation, and holds office for life. He is assisted by a council consisting of a representative from each province. The provincials, rectors of colleges, heads of professed houses, and masters of notices are appointed by the general, usually, however, only for a definite number of years, while all minor officials are appointed by the provincial. The novitiate lasts for two years during which time candidates for admission to the order are engaged almost entirely in prayer, meditation, and spiritual reading. When the novitiate has been completed the scholasticate begins. Students are obliged to read a course in arts and philosophy and to teach in some of the colleges of the society, after which they proceed to the study of theology. When the theological course has been ended they are admitted as coadjutors or professed members according to their ability and conduct. Between these two bodies, the coadjutors and the professed, there is very little difference, except that the professed in addition to the ordinary vows pledge themselves to go wherever the Pope may send them, and besides, it is from this body as a rule that the higher officials of the order are selected. Lay brothers are also attached to the society.

When the Society of Jesus was founded, Protestantism had already made great strides in Northern Europe, and though the Latin countries were not then affected no man could foresee what change a decade of years might bring. St. Ignatius adopted the best precautions against the spread of heresy. While he himself remained in Rome engaged in organizing the members of his society and in establishing colleges and charitable institutions, he sent his followers to all parts of Italy. Bishops availed themselves freely of their services as preachers and teachers. Colleges were opened in Venice, Naples, Bologna, Florence, and in many other leading cities. St. Charles Borromeo became the patron and defender of the society in Milan. Everywhere the labors of the Jesuits led to a great religious revival, while by means of their colleges they strengthened the faith of the rising generation. In Spain, too, the home of St. Ignatius the Jesuits received a friendly welcome. Their colleges were crowded with students, as were their churches with the faithful. Difficulties, indeed, arose owing to the tendency of some of the Spanish Jesuits to have none but Spanish superiors, but with a little prudence these difficulties were overcome in 1593. Most of the best known writers on ecclesiastical subjects, Vasquez, Suarez, De Lugo, and Ripalda on Dogmatic Theology, Sanchez on Moral Theology, and Maldonatus and Pereira on Scripture belonged to the Spanish province.

In France the society met with serious difficulties at first. Hatred of Spain and of everything that savored of Spanish origin, dislike of what was considered the excessive loyalty of the society to the Pope, and jealousy on the part of the University of Paris were the principal obstacles that were to be overcome. But notwithstanding these the Jesuits found a home in Paris, where they opened the College de Clermont (Louis-le-Grand), and they founded similar colleges in several of the leading cities of France. In the struggle against the Calvinists they were of great assistance to the Catholic body. The progress of their numerous colleges and the influence which they acquired over the young men roused the fierce opposition of the University, but being befriended by the court, where they were retained as royal confessors, the Jesuits were enabled to hold their ground. During the wars of the League against Henry III. and Henry of Navarre, though their position was one of extreme delicacy, the prudent action of their general, Aquaviva, in recommending his subjects to respect the consciences of both parties saved the situation. They were, however, expelled from Paris in 1594, but Henry IV. allowed them to return in 1603.

In the German States, Hungary, and Poland, where the fate of Catholicity seemed trembling in the balance, the Jesuit Fathers stayed what threatened to be a triumphal progress for Protestantism. St. Ignatius soon dispatched some of his disciples to the scene of conflict under the leadership of the Blessed Peter Canisius. By his sermons, his lectures as professor, his prudent suggestions to those in authority, as well as by his controversial writings, and more particularly his celebrated Catechism, Canisius did more to stay the advance of Protestantism in Germany than any single individual of his age. Colleges were founded in Vienna, Ingoldstadt, Treves, Mainz, and in most of the cities of Germany that were not subject to the Protestant princes. From these colleges went forth young men who were determined to resist the further encroachments of heresy. Maximilian of Bavaria and the Emperor Ferdinand II., both of whom took such a prominent part in the Catholic Counter-Reformation, were pupils of the Jesuits, and were but types of the men who left their colleges. In Hungary, too, and in Poland the tide was turned in favor of the Catholic Church mainly by the exertions of the Jesuits. In Ireland, England and Scotland, in the Netherlands, and Sweden, in a word wherever Catholic interests were endangered, the Jesuits risked their lives in defense of the Catholic religion. It is on account of the defeats that they inflicted on heresy at this period that the hatred of the Jesuits is so deep-rooted and so universal amongst Protestants even to the present day.

The Ursulines, so called from their patron St. Ursula, began as a religious association of pious ladies formed by Angela de’ Merici (Angela of Brescia) in 1537. At first the aim of the association was to reclaim fallen women, to visit the sick, and to educate the young. The members lived in their own homes according to a scheme of life drawn up for their guidance, meeting only for certain spiritual exercises. In 1535 the foundress succeeded in bringing a few of them together into a small community. After her death in 1540 the community increased in numbers, and was approved by Paul III., who allowed the Ursulines to change their rules according to circumstances. For a long time the Ursulines did not spread outside Brescia, but as their work became known, particularly their work as educationalists, they were invited to other parts of Italy. In Milan they had a warm friend in the person of its Cardinal Archbishop, St. Charles Borromeo. The first community of the Ursulines was formed in France by Madame de Beuve. A rule was drawn up by Father Gonterey, S.J., and others of his society, and approved by Paul V. (1612). In a comparatively short time the Ursulines spread over most of the Catholic countries of Europe, so that nearly all the most modern and best equipped schools for Catholic girls were in their hands. In 1639 they went to Canada where they opened the convent known as the Hotel-Dieu at Quebec, and in 1727 they settled in New Orleans.

St. Teresa (1515-82) is the reformer rather than the foundress of the Carmelite nuns. Being anxious from an early age to follow her religious vocation, much against the wishes of her father she entered the convent of the Carmelite nuns at Avila (1535). After her profession she fell ill, and for years was subject to excruciating torture. During this period she turned her mind completely to spiritual subjects, and was visited by God with most extraordinary marks of divine favor, an account of which is to be found in her life written by herself, in her Relations, and in many other of her works. She determined to return to the primitive austerity of the Carmelite rule, and in 1562 she founded the first convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns at Avila. Through her exertions other convents of the order adopted the reform, and in 1580 the existence of the Discalced Carmelites as a separate order was approved. She died in 1582, and forty years later she was canonized by Gregory XV.

The Sisters of the Visitation were established by St. Francis de Sales and St. Frances de Chantal. St. Francis de Sales (1567-1622), so called from the castle of Sales in Savoy at which he was born, made his rhetoric and philosophical studies at Paris under the Jesuits. From Paris he went to Padua for law, and having received his diploma he returned to his native country, where his father had secured for him a place as senator and had arranged a very desirable marriage. But St. Francis, feeling that he had been called by God to another sphere of life, threw up his position at the bar, accepted the office of provost of the chapter of Geneva, and received Holy Orders (1593). A great part of the diocese of Geneva was at this time overrun by the heretics. St. Francis threw himself with ardor into the work of converting those who had fallen away especially in the district of Le Chablais, where he won over thousands to the faith. He became coadjutor-bishop of Geneva, and on the death of his friend Claude de Granier he was appointed to the See (1602). In conjunction with Madam de Chantal he established a community of women at Annecy in 1610. His idea at first was that the little community should not be bound by the enclosure, but should devote themselves to their own sanctification and to the visitation of the sick and the poor. Objections, however, having been raised against such an innovation, he drew up for the community a rule based mainly on the rule of St. Augustine. In 1618 the society received recognition as a religious order under the title of the Order of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin. The order undertook the work of educating young girls as well as of visiting the sick. It spread rapidly in Italy, France, Germany, Poland, and later on in the United States.

The Sisters of Charity, or the Grey Sisters as they were called, were founded by St. Vincent de Paul. While St. Vincent was cure of Chatillon-les-Dombes he established in the parish a confraternity of charitable ladies for the care of the sick, the poor, and the orphans. The experiment was so successful that he founded similar confraternities in Paris, and wherever he gave missions throughout the country. Having found, however, that in Paris the ladies of charity were accustomed to entrust the work to their servants he brought a number of young girls from the country, who could be relied upon to carry out his wishes. These he looked after with a special solicitude, and in 1633 Madam Le Gras took a house in Paris, where she brought together a few of the most promising of them to form a little community. In 1642 after the community had moved into a house opposite St. Lazare, some of the sisters were allowed to take vows. The Sisters of Charity have been at all times exceedingly popular in France. By their schools, their orphanages, their hospitals, and by their kindness to the poor and the suffering they won for themselves a place in the hearts of the French people. For a while during the worst days of the Revolution their work was suspended, and their communities were disbanded; but their suppression was deplored so generally that in 1801 the Superioress was commanded to re- rganize the society. Outside France the Sisters of Charity had several houses in Poland, Switzerland, Spain, and Germany.

Mary Ward (1585-1645) was born of a good Catholic family in England. She joined the Poor Clares at St. Omer in 1600, but, preferring an active to a contemplative life, she gathered around her a few companions, and formed a little community at St. Omer mainly for the work of education. According to her plan, which was derived in great measure from the constitution of the Society of Jesus (hence the name Jesuitesses given to her followers by her opponents), her sisters were not bound by the enclosure, were not to wear any distinctive dress, and were to be subject directly only to Rome. Serious objections were raised immediately against such an institute, particularly as Pius V. had declared expressly that the enclosure and solemn vows were essential conditions for the recognition of religious communities of women. Branches were opened in the Netherlands, Austria, and Italy under the patronage of the highest civil authorities. As the opponents of the community continued their attacks the foundress was summoned to Rome to make her defense (1629), but in the following year the decree of suppression was issued. The house in Munich was allowed to continue, and at the advice of the Pope she opened a house in Rome. The principal change introduced was that the houses should be subject to the bishops of the dioceses in which they were situated. At last in 1703, on the petition of Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria and of Mary the wife of James II., the rule was approved formally by Clement XI. The society continued to spread especially in Bavaria. The followers of Mary Ward are designated variously, the Institute of Mary, Englische Fraulein, and Loreto Nuns from the name given to Rathfarnham, the mother-house of the Irish branch, founded by Frances Ball in 1821.