Christian Elements in Islamic Literature

[This is taken from Claud Field’s Mystics and Saints of Islam, originally published in 1910.]

[This is taken from Claud Field’s Mystics and Saints of Islam, originally published in 1910.]

The almost miraculous renaissance in Islam which is now proceeding in Turkey and other Mohammedan countries reminds one forcibly of Dante’s lines:

For I have seen

The thorn frown rudely all the winter long,

And after bear the rose upon its top.

— Paradiso, xiii. 133.

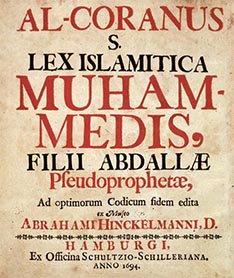

It is not perhaps fanciful to conjecture that one of the hidden causes of this renaissance is the large quantity of Christian truth which Islam literature holds, so to speak, in solution. It is a well-known fact that the Koran has borrowed largely from the Old Testament and the Apocryphal Gospels, but it is not so generally known that Mohammedan philosophers, theologians, and poets betray an acquaintance with facts and incidents of the Gospels of which the Koran contains no mention.

Leaving the Koran on one side, in the “Traditions,” i.e., sayings of Mohammed handed down by tradition, we find God represented as saying at the Judgment, “O ye sons of men, I was hungry and ye gave Me no food,” the whole of the passage in Matt. xxv. being quoted. This is remarkable, as it strikes directly at the orthodox Mohammedan conception of God as an impassible despot. Other sayings attributed to God which have a Christian ring are, “I was a hidden Treasure and desired to be known, therefore I created the world”; “If it were not for Thee, I would not have made the world” (addressed to Mohammed), evidently an echo of Col. I. 17, “All things have been created through Him and unto Him”. The writer has often heard this last saying quoted by Indian Mohammedans in controversy.

Another traditional saying attributed to Mohammed is not unlike the doctrine of the Holy Spirit: “Verily from your Lord come breathings. Be ye prepared for them.” The Second Advent is also referred to in others: “How will it be with you when God sends Jesus to judge you?” “There is no Mahdi but Jesus.” It is a well-known fact that a certain gate in Jerusalem is kept walled up because the Mohammedans believe that Jesus will pass through it when He returns.

Some traditions have twisted Gospel parables, etc., in favour of Mohammedanism. Thus in the mention of the parable of the hired labourers, the first two sets of labourers are said to mean Jews and Christians, and the last comers, who receive an equal wage, though grumbled at by the others, are believed to indicate the Mohammedans. Other traditions give one of Christ’s sayings a grotesquely literal dress. Thus our Lord is said to have met a fox, and to have said, “Fox! where art thou going?” The fox replied, to his home. Upon which our Lord uttered the verse, “Foxes have holes,” etc. Once when entering an Afghan village the writer was met by a Pathan, who asked if the New Testament contained that verse. This shows how even garbled traditions may predispose the Mohammedan mind for the study of the Gospels.

Tabari, the historian (d. 923 a.d.), gives an account of the Last Supper and of Christ washing the disciples’ hands (sic)—topics entirely ignored by the Koran—and quotes the saying of our Lord regarding the smiting of the Shepherd and the scattering of the sheep.

Sufi literature, representing as it does the mystical side of Islam, abounds with allusions to Scripture. Al Ghazzali, the great opponent of Averroes (1058-1111 a.d.), in his Ihya-ul-ulum (“Revival of the Religious Sciences”) quotes the saying of Christ regarding the children playing in the market-place. In his Kimiya-i-Saadat (“Alchemy of Happiness”) he writes, “It is said that Jesus Christ in a vision saw this world in the form of an old woman, and asked how many husbands she had lived with. She said they were innumerable. He asked her if they had died, or had divorced her. She replied that it was neither, the fact being that she had killed all.” Here we seem to have a confused echo of the episode of the woman of Samaria. Again in the same work he says, “It is a saying of Jesus Christ that the seeker of the world is like a man suffering from dropsy; the more he drinks water the more he feels thirsty.” In the Ihya-ul-ulum, the verse “Eye hath not seen,” &c., is quoted as if from the Koran, where it nowhere occurs. Ghazzali was an ardent student of the Neo-Platonists, and through him the phrases Aql-i-Kull (—Logos) and Nafs-i-Kull (—Pneuma) passed into Sufi writings (v. Whinfield, Preface to the Masnavi).

Saadi (b. 1184 a.d.), the famous author of the Gulistan and Bostan, was for some time kept in captivity by the Crusaders. This may account for echoes of the Gospels which we find in his writings. In the Gulistan he quotes the verse, “We are members of one another,” and in the Bostan the parable of the Pharisee and Publican is told in great detail.

But of all the Mohammedan writers, none bears such distinct traces of Christian influence as Jalaluddin Rumi, the greatest of the Sufi poets, who is to this day much studied in Persia, Turkey and India. In the first book of his Masnavi he has a strange story of a vizier who persuaded his king, a Jewish persecutor of the Christians, to mutilate him. He then went to the Christians and said, “See what I have suffered for your religion.” After gaining their confidence and being chosen their guide, he wrote epistles in different directions to the chief Christians, contradicting each other, maintaining in one that man is saved by grace, and in another that salvation rests upon works, &c. Thus he brought their religion into inextricable confusion. This is evidently aimed at St. Paul, and it is a curious fact that Jalaluddin Rumi spent most of his life at Iconium, where some traditions of the apostle’s teaching must have lingered. Other allusions to the Gospel narrative in the Masnavi are found in the mention of John the Baptist leaping in his mother’s womb, of Christ walking on the water, etc., none of which occur in the Koran. Isolated verses of Jalaluddin’s clearly show a Christian origin:

I am the sweet-smiling Jesus,

And the world is alive by Me.

I am the sunlight falling from above,

Yet never severed from the Sun I love.

It will be seen that Jalaluddin gives our Lord a much higher rank than is accorded to Him in the Koran, which says, “And who could hinder God if He chose to destroy Mary and her son together?”

A strange echo of the Gospel narrative is found in the story of the celebrated Sufi, Mansur-al-Hallaj, who was put to death at Bagdad, 919 a.d., for exclaiming while in a state of mystic ecstacy, “I am the Truth.” Shortly before he died he cried out, “My Friend (God) is not guilty of injuring me; He gives me to drink what as Master of the feast He drinks Himself” (Whinfield, preface to the Masnavi). Notwithstanding the apparent blasphemy of Mansur’s exclamation, he has always been the object of eulogy by Mohammedan poets. Even the orthodox Afghan poet, Abdurrahman, says of him:

Every man who is crucified like Mansur,

After death his cross becomes a fruit-bearing tree.

Many of the favourite Sufi phrases, “The Perfect Man,” “The new creation,” “The return to God,” have a Christian sound, and the modern Babi movement which has so profoundly influenced Persian life and thought owes its very name to the saying of Christ, “I am the Door” (“Ana ul Bab”), adopted by Mirza Ali, the founder of the sect.

When Henry Martyn reached Shiraz in 1811, he found his most attentive listeners among the Sufis. “These Sufis,” he writes in his diary, “are quite the Methodists of the East. They delight in everything Christian except in being exclusive. They consider they all will finally return to God, from whom they emanated.”

It is certainly noteworthy that some of the highly educated Indian converts from Islam to Christianity have been men who have passed through a stage of Sufism, e.g., Moulvie Imaduddin of Amritsar, on whom Archbishop Benson conferred a D.D. degree, and Safdar Ali, late Inspector of Schools at Jabalpur. In one of the semi-domes of the Mosque of St. Sophia at Constantinople is a gigantic figure of Christ in mosaic, which the Mohammedans have not destroyed, but overlaid with gilding, yet so that the outlines of the figure are still visible. Is it not a parable?