The Gods of Gaul and the Continental Celts

By J. A. MacCulloch

By J. A. MacCulloch

The passage in which Caesar sums up the Gaulish pantheon runs: “They worship chiefly the god Mercury; of him there are many symbols, and they regard him as the inventor of all the arts, as the guide of travellers, and as possessing great influence over bargains and commerce. After him they worship Apollo and Mars, Juppiter and Minerva. About these they hold much the same beliefs as other nations. Apollo heals diseases, Minerva teaches the elements of industry and the arts, Jupiter rules over the heavens, Mars directs war…. All the Gauls assert that they are descended from Dispater, their progenitor.”[53]

As will be seen in this chapter, the Gauls had many other gods than these, while the Roman gods, by whose names Caesar calls the Celtic divinities, probably only approximately corresponded to them in functions. As the Greeks called by the names of their own gods those of Egypt, Persia, and Babylonia, so the Romans identified Greek, Teutonic, and Celtic gods with theirs. The identification was seldom complete, and often extended only to one particular function or attribute. But, as in Gaul, it was often part of a state policy, and there the fusion of cults was intended to break the power of the Druids. The Gauls seem to have adopted Roman civilisation easily, and to have acquiesced in the process of assimilation of their divinities to those of their conquerors. Hence we have thousands of inscriptions in which a god is called by the name of the Roman deity to whom he was assimilated and by his own Celtic name—Jupiter Taranis, Apollo Grannus, etc. Or sometimes to the name of the Roman god is added a descriptive Celtic epithet or a word derived from a Celtic place-name. Again, since Augustus reinstated the cult of the Lares, with himself as chief Lar, the epithet Augustus was given to all gods to whom the character of the Lares could be ascribed, e.g. Belenos Augustus. Cults of local gods became cults of the genius of the place, coupled with the genius of the emperor. In some cases, however, the native name stands alone. The process was aided by art. Celtic gods are represented after Greco-Roman or Greco-Egyptian models. Sometimes these carry a native divine symbol, or, in a few cases, the type is purely native, e.g. that of Cernunnos. Thus the native paganism was largely transformed before Christianity appeared in Gaul. Many Roman gods were worshipped as such, not only by the Romans in Gaul, but by the Gauls, and we find there also traces of the Oriental cults affected by the Romans.[54]

There were probably in Gaul many local gods, tribal or otherwise, of roads and commerce, of the arts, of healing, etc., who, bearing different names, might easily be identified with each other or with Roman gods. Caesar’s Mercury, Mars, Minerva, etc., probably include many local Minervas, Mars, and Mercuries. There may, however, have been a few great gods common to all Gaul, universally worshipped, besides the numerous local gods, some of whom may have been adopted from the aborigines. An examination of the divine names in Holder’s Altceltischer Sprachschatz will show how numerous the local gods of the continental Celts must have been. Professor Anwyl reckons that 270 gods are mentioned once on inscriptions, 24 twice, 11 thrice, 10 four times, 3 five times, 2 seven times, 4 fifteen times, 1 nineteen times (Grannos), and 1 thirty-nine times (Belenos).[55]

The god or gods identified with Mercury were very popular in Gaul, as Caesar’s words and the witness of place-names derived from the Roman name of the god show. These had probably supplanted earlier names derived from those of the corresponding native gods. Many temples of the god existed, especially in the region of the Allobrogi, and bronze statuettes of him have been found in abundance. Pliny also describes a colossal statue designed for the Arverni who had a great temple of the god on the Puy de Dome.[56] Mercury was not necessarily the chief god, and at times, e.g. in war, the native war-gods would be prominent. The native names of the gods assimilated to Mercury are many in number; in some cases they are epithets, derived from the names of places where a local “Mercury” was worshipped, in others they are derived from some function of the gods.[57] One of these titles is Artaios, perhaps cognate with Irish art, “god,” or connected with artos, “bear.” Professor Rhys, however, finds its cognate in Welsh ar, “ploughed land,” as if one of the god’s functions connected him with agriculture.[58] This is supported by another inscription to Mercurius Cultor at Wurtemberg. Local gods of agriculture must thus have been assimilated to Mercury. A god Moccus, “swine,” was also identified with Mercury, and the swine was a frequent representative of the corn-spirit or of vegetation divinities in Europe. The flesh of the animal was often mixed with the seed corn or buried in the fields to promote fertility. The swine had been a sacred animal among the Celts, but had apparently become an anthropomorphic god of fertility, Moccus, assimilated to Mercury, perhaps because the Greek Hermes caused fertility in flocks and herds. Such a god was one of a class whose importance was great among the Celts as an agricultural people.

Commerce, much developed among the settled Gauls, gave rise to a god or gods who guarded roads over which merchants travelled, and boundaries where their transactions took place. Hence we have an inscription from Yorkshire, “To the god who invented roads and paths,” while another local god of roads, equated with Mercury, was Cimiacinus.[59]

Another god, Ogmios, a native god of speech, who draws men by chains fastened to the tip of his tongue, is identified in Lucian with Heracles, and is identical with the Goidelic Ogma.[60] Eloquence and speech are important matters among primitive peoples, and this god has more likeness to Mercury as a culture-god than to Heracles, Greek writers speaking of eloquence as binding men with the chains of Hermes.

Several local gods, of agriculture, commerce, and culture, were thus identified with Mercury, and the Celtic Mercury was sometimes worshipped on hilltops, one of the epithets of the god, Dumias, being connected with the Celtic word for hill or mound. Irish gods were also associated with mounds.

Many local gods were identified with Apollo both in his capacity of god of healing and also that of god of light.[61] The two functions are not incompatible, and this is suggested by the name Grannos, god of thermal springs both in Britain and on the Continent. The name is connected with a root which gives words meaning “burning,” “shining,” etc., and from which comes also Irish grian, “sun.” The god is still remembered in a chant sung round bonfires in Auvergne. A sheaf of corn is set on fire, and called “Granno mio,” while the people sing, “Granno, my friend;

Granno, my father; Granno, my mother.”[62] Another god of thermal springs was Borvo, Bormo, or Bormanus, whose name is derived from borvo, whence Welsh berw, “boiling,” and is evidently connected with the bubbling of the springs.[63] Votive tablets inscribed Grannos or Borvo show that the offerers desired healing for themselves or others.

The name Belenos found over a wide area, but mainly in Aquileia, comes from belo-s, bright, and probably means “the shining one.” It is thus the name of a Celtic sun-god, equated with Apollo in that character. If he is the Belinus referred to by Geoffrey of Monmouth,[64] his cult must have extended into Britain from the Continent, and he is often mentioned by classical writers, while much later Ausonius speaks of his priest in Gaul.[65] Many place and personal names point to the popularity of his cult, and inscriptions show that he, too, was a god of health and of healing-springs. The plant Belinuntia was called after him and venerated for its healing powers.[66] The sun-god’s functions of light and fertility easily passed over into those of health-giving, as our study of Celtic festivals will show.

A god with the name Maponos, connected with words denoting “youthfulness,” is found in England and Gaul, equated with Apollo, who himself is called Bonus Puer in a Dacian inscription. Another god Mogons or Mogounos, whose name is derived from Mago, “to increase,” and suggests the idea of youthful strength, may be a form of the sun-god, though some evidence points to his having been a sky-god.[67]

The Celtic Apollo is referred to by classical writers. Diodorus speaks of his circular temple in an island of the Hyperboreans, adorned with votive offerings. The kings of the city where the temple stood, and its overseers, were called “Boreads,” and every nineteenth year the god appeared dancing in the sky at the spring equinox.[68] The identifications of the temple with Stonehenge and of the Boreads with the Bards are quite hypothetical. Apollonius says that the Celts regarded the waters of Eridanus as due to the tears of Apollo—probably a native myth attributing the creation of springs and rivers to the tears of a god, equated by the Greeks with Apollo.[69] The Celtic sun-god, as has been seen, was a god of healing springs.

Some sixty names or titles of Celtic war-gods are known, generally equated with Mars.[70] These were probably local tribal divinities regarded as leading their worshippers to battle. Some of the names show that these gods were thought of as mighty warriors, e.g. Caturix, “battle-king,” Belatu-Cadros—a common name in Britain—perhaps meaning “comely in slaughter,”[71] and Albiorix, “world-king.”[72] Another name, Rigisamus, from rix and samus, “like to,” gives the idea of “king-like.”[73]

Toutatis, Totatis, and Tutatis are found in inscriptions from Seckau, York, and Old Carlisle, and may be identified with Lucan’s Teutates, who with Taranis and Esus mentioned by him, is regarded as one of three pan-Celtic gods.[74] Had this been the case we should have expected to find many more inscriptions to them. The scholiast on Lucan identifies Teutates now with Mars, now with Mercury. His name is connected with teuta, “tribe,” and he is thus a tribal war-god, regarded as the embodiment of the tribe in its warlike capacity.

Neton, a war-god of the Accetani, has a name connected with Irish nia, “warrior,” and may be equated with the Irish war-god Net. Another god, Camulos, known from British and continental inscriptions, and figured on British coins with warlike emblems, has perhaps some connection with Cumal, father of Fionn, though it is uncertain whether Cumal was an Irish divinity.[75]

Another god equated with Mars is the Gaulish Braciaca, god of malt. According to classical writers, the Celts were drunken race, and besides importing quantities of wine, they made their own native drinks, e.g. [Greek: chourmi], the Irish cuirm, and braccat, both made from malt (braich).[76] These words, with the Gaulish brace, “spelt,”[77] are connected with the name of this god, who was a divine personification of the substance from which the drink was made which produced, according to primitive ideas, the divine frenzy of intoxication. It is not clear why Mars should have been equated with this god.

Caesar says that the Celtic Jupiter governed heaven. A god who carries a wheel, probably a sun-god, and another, a god of thunder, called Taranis, seem to have been equated with Juppiter. The sun-god with the wheel was not equated with Apollo, who seems to have represented Celtic sun-gods only in so far as they were also gods of healing. In some cases the god with the wheel carries also a thunderbolt, and on some altars, dedicated to Juppiter, both a wheel and a thunderbolt are figured. Many races have symbolised the sun as a circle or wheel, and an old Roman god, Summanus, probably a sun-god, later assimilated to Juppiter, had as his emblem a wheel. The Celts had the same symbolism, and used the wheel symbol as an amulet,[78] while at the midsummer festivals blazing wheels, symbolising the sun, were rolled down a slope. Possibly the god carries a thunderbolt because the Celts, like other races, believed that lightning was a spark from the sun.

Three divinities have claims to be the god whom Caesar calls Dispater—a god with a hammer, a crouching god called Cernunnos, and a god called Esus or Silvanus. Possibly the native Dispater was differently envisaged in different districts, so that these would be local forms of one god.

- The god Taranis mentioned by Lucan is probably the Taranoos and Taranucnos of inscriptions, sometimes equated with Juppiter.[79] These names are connected with Celtic words for “thunder”; hence Taranis is a thunder-god. The scholiasts on Lucan identify him now with Juppiter, now with Dispater. This latter identification is supported by many who regard the god with the hammer as at once Taranis and Dispater, though it cannot be proved that the god with the hammer is Taranis. On one inscription the hammer-god is called Sucellos; hence we may regard Taranis as a distinct deity, a thunder-god, equated with Juppiter, and possibly represented by the Taran of the Welsh tale ofKulhwych.[80]

Primitive men, whose only weapon and tool was a stone axe or hammer, must have regarded it as a symbol of force, then of supernatural force, hence of divinity. It is represented on remains of the Stone Age, and the axe was a divine symbol to the Mycenaeans, a hieroglyph of Neter to the Egyptians, and a worshipful object to Polynesians and Chaldeans. The cult of axe or hammer may have been widespread, and to the Celts, as to many other peoples, it was a divine symbol. Thus it does not necessarily denote a thunderbolt, but rather power and might, and possibly, as the tool which shaped things, creative might. The Celts made ex voto hammers of lead, or used axe-heads as amulets, or figured them on altars and coins, and they also placed the hammer in the hand of a god.[81]

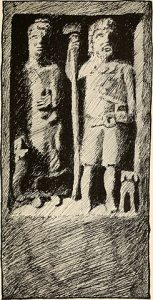

The god with the hammer is a gracious bearded figure, clad in Gaulish dress, and he carries also a cup. His plastic type is derived from that of the Alexandrian Serapis, ruler of the underworld, and that of Hades-Pluto.[82] His emblems, especially that of the hammer, are also those of the Pluto of the Etruscans, with whom the Celts had been in contact.[83] He is thus a Celtic Dispater, an underworld god, possibly at one time an Earth-god and certainly a god of fertility, and ancestor of the Celtic folk. In some cases, like Serapis, he carries a modius on his head, and this, like the cup, is an emblem of chthonian gods, and a symbol of the fertility of the soil. The god being benevolent, his hammer, like the tool with which man forms so many things, could only be a symbol of creative force.[84] As an ancestor of the Celts, the god is naturally represented in Celtic dress. In one bas-relief he is called Sucellos, and has a consort, Nantosvelta.[85] Various meanings have been assigned to “Sucellos,” but it probably denotes the god’s power of striking with the hammer. M. D’Arbois hence regards him as a god of blight and death, like Balor.[86] But though this Celtic Dispater was a god of the dead who lived on in the underworld, he was not necessarily a destructive god. The underworld god was the god from whom or from whose kingdom men came forth, and he was also a god of fertility. To this we shall return.

- A bearded god, probably squatting, with horns from each of which hangs a torque, is represented on an altar found at Paris.[87] He is called Cernunnos, perhaps “the horned,” fromcerna, “horn,” and a whole group of nameless gods, with similar or additional attributes, have affinities with him.

(a) A bronze statuette from Autun represents a similar figure, probably horned, who presents a torque to two ram’s-headed serpents. Fixed above his ears are two small heads.[88] On a monument from Vandoeuvres is a squatting horned god, pressing a sack. Two genii stand beside him on a serpent, while one of them holds a torque.[89]

(b) Another squatting horned figure with a torque occurs on an altar from Reims. He presses a bag, from which grain escapes, and on it an ox and stag are feeding. A rat is represented on the pediment above, and on either side stand Apollo and Mercury.[90] On the altar of Saintes is a squatting but headless god with torque and purse. Beside him is a goddess with a cornucopia, and a smaller divinity with a cornucopia and an apple. A similar squatting figure, supported by male and female deities, is represented on the other side of the altar.[91] On the altar of Beaune are three figures, one horned with a cornucopia, another three-headed, holding a basket.[92] Three figures, one female and two male, are found on the Dennevy altar. One god is three-faced, the other has a cornucopia, which he offers to a serpent.[93]

(c) Another image represents a three-faced god, holding a serpent with a ram’s head.[94]

(d) Above a seated god and goddess on an altar from Malmaison is a block carved to represent three faces. To be compared with these are seven steles from Reims, each with a triple face but only one pair of eyes. Above some of these is a ram’s head. On an eighth stele the heads are separated.[95]

Cernunnos may thus have been regarded as a three-headed, horned, squatting god, with a torque and ram’s-headed serpent. But a horned god is sometimes a member of a triad, perhaps representing myths in which Cernunnos was associated with other gods. The three-headed god may be the same as the horned god, though on the Beaune altar they are distinct. The various representations are linked together, but it is not certain that all are varying types of one god. Horns, torque, horned snake, or even the triple head may have been symbols pertaining to more than one god, though generally associated with Cernunnos.

The squatting attitude of the god has been differently explained, and its affinities regarded now as Buddhist, now as Greco-Egyptian.[96] But if the god is a Dispater, and the ancestral god of the Celts, it is natural, as M. Mowat points out, to represent him in the typical attitude of the Gauls when sitting, since they did not use seats.[97] While the horns were probably symbols of power and worn also by chiefs on their helmets,[98] they may also show that the god was an anthropomorphic form of an earlier animal god, like the wolf-skin of other gods. Hence also horned animals would be regarded as symbols of the god, and this may account for their presence on the Reims monument. Animals are sometimes represented beside the divinities who were their anthropomorphic forms.[99] Similarly the ram’s-headed serpent points to animal worship. But its presence with three-headed and horned gods is enigmatic, though, as will be seen later, it may have been connected with a cult of the dead, while the serpent was a chthonian animal.[100] These gods were gods of fertility and of the underworld of the dead. While the bag or purse (interchangeable with the cornucopia) was a symbol of Mercury, it was also a symbol of Pluto, and this may point to the fact that the gods who bear it had the same character as Pluto. The significance of the torque is also doubtful, but the Gauls offered torques to the gods, and they may have been regarded as vehicles of the warrior’s strength which passed from him to the god to whom the victor presented it.

Though many attempts have been made to prove the non-Celtic origin of the three-headed divinities or of their images,[101] there is no reason why the conception should not be Celtic, based on some myth now lost to us. The Celts had a cult of human heads, and fixed them up on their houses in order to obtain the protection of the ghost. Bodies or heads of dead warriors had a protective influence on their land or tribe, and myth told how the head of the god Bran saved his country from invasion. In other myths human heads speak after being cut off.[102] It might thus easily have been believed that the representation of a god’s head had a still more powerful protective influence, especially when it was triplicated, thus looking in all directions, like Janus.

The significance of the triad on these monuments is uncertain but since the supporting divinities are now male, now female, now male and female, it probably represents myths of which the horned or three-headed god was the central figure. Perhaps we shall not be far wrong in regarding such gods, on the whole, as Cernunnos, a god of abundance to judge by his emblems, and by the cornucopia held by his companions, probably divinities of fertility. In certain cases figures of squatting and horned goddesses with cornucopia occur.[103] These may be consorts of Cernunnos, and perhaps preceded him in origin. We may also go further and see in this god of abundance and fertility at once an Earth and an Under-earth god, since earth and under-earth are much the same to primitive thought, and fertility springs from below the earth’s surface. Thus Cernunnos would be another form of the Celtic Dispater. Generally speaking, the images of Cernunnos are not found where those of the god with the hammer (Dispater) are most numerous. These two types may thus be different local forms of Dispater. The squatting attitude of Cernunnos is natural in the image of the ancestor of a people who squatted. As to the symbols of plenty, we know that Pluto was confounded with Plutus, the god of riches, because corn and minerals came out of the earth, and were thus the gifts of an Earth or Under-earth god. Celtic myth may have had the same confusion.

On a Paris altar and on certain steles a god attacks a serpent with a club. The serpent is a chthonian animal, and the god, called Smertullos, may be a Dispater.[104] Gods who are anthropomorphic forms of earlier animal divinities, sometimes have the animals as symbols or attendants, or are regarded as hostile to them. In some cases Dispater may have outgrown the serpent symbolism, the serpent being regarded locally as his foe; this assumes that the god with the club is the same as the god with the hammer. But in the case of Cernunnos the animal remained as his symbol.

Dispater was a god of growth and fertility, and besides being lord of the underworld of the dead, not necessarily a dark region or the abode of “dark” gods as is so often assumed by writers on Celtic religion, he was ancestor of the living. This may merely have meant that, as in other mythologies, men came to the surface of the earth from an underground region, like all things whose roots struck deep down into the earth. The lord of the underworld would then easily be regarded as their ancestor.[105]

- The hammer and the cup are also the symbols of a god called Silvanus, identified by M. Mowat with Esus,[106] a god represented cutting down a tree with an axe. Axe and hammer, however, are not necessarily identical, and the symbols are those of Dispater, as has been seen. A purely superficial connection between the Roman Silvanus and the Celtic Dispater may have been found by Gallo-Roman artists in the fact that both wear a wolf-skin, while there may once have been a Celtic wolf totem-god of the dead.[107] The Roman god was also associated with the wolf. This might be regarded as one out of many examples of a mere superficial assimilation of Roman and Celtic divinities, but in this case they still kept certain symbols of the native Dispater—the cup and hammer. Of course, since the latter was also a god of fertility, there was here another link with Silvanus, a god of woods and vegetation. The cult of the god was widespread—in Spain, S. Gaul, the Rhine provinces, Cisalpine Gaul, Central Europe and Britain. But one inscription gives the name Selvanos, and it is not impossible that there was a native god Selvanus. If so, his name may have been derived fromselva, “possession,” Irishsealbh, “possession,” “cattle,” and he may have been a chthonian god of riches, which in primitive communities consisted of cattle.[108] Domestic animals, in Celtic mythology, were believed to have come from the god’s land. Selvanus would thus be easily identified with Silvanus, a god of flocks.

Thus the Celtic Dispater had various names and forms in different regions, and could be assimilated to different foreign gods. Since Earth and Under-earth are so nearly connected, this divinity may once have been an Earth-god, and as such perhaps took the place of an earlier Earth-mother, who now became his consort or his mother. On a monument from Salzbach, Dispater is accompanied by a goddess called Aeracura, holding a basket of fruit, and on another monument from Ober-Seebach, the companion of Dispater holds a cornucopia. In the latter instance Dispater holds a hammer and cup, and the goddess may be Aeracura. Aeracura is also associated with Dispater in several inscriptions.[109] It is not yet certain that she is a Celtic goddess, but her presence with this evidently Celtic god is almost sufficient proof of the fact. She may thus represent the old Earth-goddess, whose place the native Dispater gradually usurped.

Thus the Celtic Dispater had various names and forms in different regions, and could be assimilated to different foreign gods. Since Earth and Under-earth are so nearly connected, this divinity may once have been an Earth-god, and as such perhaps took the place of an earlier Earth-mother, who now became his consort or his mother. On a monument from Salzbach, Dispater is accompanied by a goddess called Aeracura, holding a basket of fruit, and on another monument from Ober-Seebach, the companion of Dispater holds a cornucopia. In the latter instance Dispater holds a hammer and cup, and the goddess may be Aeracura. Aeracura is also associated with Dispater in several inscriptions.[109] It is not yet certain that she is a Celtic goddess, but her presence with this evidently Celtic god is almost sufficient proof of the fact. She may thus represent the old Earth-goddess, whose place the native Dispater gradually usurped.

Lucan mentions a god Esus, who is represented on a Paris altar as a woodman cutting down a tree, the branches of which are carried round to the next side of the altar, on which is represented a bull with three cranes—Tarvos Trigaranos. The same figure, unnamed, occurs on another altar at Treves, but in this case the bull’s head appears in the branches, and on them sit the birds. M. Reinach applies one formula to the subjects of these altars—“The divine Woodman hews the Tree of the Bull with Three Cranes.”[110] The whole represents some myth unknown to us, but M. D’Arbois finds in it some allusion to events in the Cuchulainn saga. To this we shall return.[111] Bull and tree are perhaps both divine, and if the animal, like the images of the divine bull, is three-horned, then the three cranes (garanus, “crane”) may be a rebus for three-horned (trikeras), or more probably three-headed (trikarenos).[112] In this case woodman, tree, and bull might all be representatives of a god of vegetation. In early ritual, human, animal, or arboreal representatives of the god were periodically destroyed to ensure fertility, but when the god became separated from these representatives, the destruction or slaying was regarded as a sacrifice to the god, and myths arose telling how he had once slain the animal. In this case, tree and bull, really identical, would be mythically regarded as destroyed by the god whom they had once represented. If Esus was a god of vegetation, once represented by a tree, this would explain why, as the scholiast on Lucan relates, human sacrifices to Esus were suspended from a tree. Esus was worshipped at Paris and at Treves; a coin with the name AEsus was found in England; and personal names like Esugenos, “son of Esus,” and Esunertus, “he who has the strength of Esus,” occur in England, France, and Switzerland.[113] Thus the cult of this god may have been comparatively widespread. But there is no evidence that he was a Celtic Jehovah or a member, with Teutates and Taranis, of a pan-Celtic triad, or that this triad, introduced by Gauls, was not accepted by the Druids.[114] Had such a great triad existed, some instance of the occurrence of the three names on one inscription would certainly have been found. Lucan does not refer to the gods as a triad, nor as gods of all the Celts, or even of one tribe. He lays stress merely on the fact that they were worshipped with human sacrifice, and they were apparently more or less well-known local gods.[115]

The insular Celts believed that some of their gods lived on or in hills. We do not know whether such a belief was entertained by the Gauls, though some of their deities were worshipped on hills, like the Puy de Dome. There is also evidence of mountain worship among them. One inscription runs, “To the Mountains”; a god of the Pennine Alps, Poeninus, was equated with Juppiter; and the god of the Vosges mountains was called Vosegus, perhaps still surviving in the giant supposed to haunt them.[116]

Certain grouped gods, Dii Casses, were worshipped by Celts on the right bank of the Rhine, but nothing is known regarding their functions, unless they were road gods. The name means “beautiful” or “pleasant,” and Cassi appears in personal and tribal names, and also in Cassiterides, an early name of Britain, perhaps signifying that the new lands were “more beautiful” than those the Celts had left. When tin was discovered in Britain, the Mediterranean traders called it [Greek: chassiteros], after the name of the place where it was found, as cupreus, “copper,” was so called from Cyprus.[117]

Many local tutelar divinities were also worshipped. When a new settlement was founded, it was placed under the protection of a tribal god, or the name of some divinised river on whose banks the village was placed, passed to the village itself, and the divinity became its protector. Thus Dea Bibracte, Nemausus, and Vasio were tutelar divinities of Bibracte, Nimes, and Vaison. Other places were called after Belenos, or a group of divinities, usually the Matres with a local epithet, watched over a certain district.[118] The founding of a town was celebrated in an annual festival, with sacrifices and libations to the protecting deity, a practice combated by S. Eloi in the eighth century. But the custom of associating a divinity with a town or region was a great help to patriotism. Those who fought for their homes felt that they were fighting for their gods, who also fought on their side. Several inscriptions, “To the genius of the place,” occur in Britain, and there are a few traces of tutelar gods in Irish texts, but generally local saints had taken their place.

The Celtic cult of goddesses took two forms, that of individual and that of grouped goddesses, the latter much more numerous than the grouped gods. Individual goddesses were worshipped as consorts of gods, or as separate personalities, and in the latter case the cult was sometimes far extended. Still more popular was the cult of grouped goddesses. Of these the Matres, like some individual goddesses, were probably early Earth-mothers, and since the primitive fertility-cults included all that might then be summed up as “civilisation,” such goddesses had already many functions, and might the more readily become divinities of special crafts or even of war. Many individual goddesses are known only by their names, and were of a purely local character.[119] Some local goddesses with different names but similar functions are equated with the same Roman goddess; others were never so equated.

The Celtic Minerva, or the goddesses equated with her, “taught the elements of industry and the arts,”[120] and is thus the equivalent of the Irish Brigit. Her functions are in keeping with the position of woman as the first civiliser—discovering agriculture, spinning, the art of pottery, etc. During this period goddesses were chiefly worshipped, and though the Celts had long outgrown this primitive stage, such culture-goddesses still retained their importance. A goddess equated with Minerva in Southern France and Britain is Belisama, perhaps from qval, “to burn” or “shine.”[121] Hence she may have been associated with a cult of fire, like Brigit and like another goddess Sul, equated with Minerva at Bath and in Hesse, and in whose temple perpetual fires burned.[122] She was also a goddess of hot springs. Belisama gave her name to the Mersey,[123] and many goddesses in Celtic myth are associated with rivers.

Some war-goddesses are associated with Mars—Nemetona (in Britain and Germany), perhaps the same as the Irish Nemon, and Cathubodua, identical with the Irish war-goddess Badb-catha, “battle-crow,” who tore the bodies of the slain.[124] Another goddess Andrasta, “invincible,” perhaps the same as the Andarta of the Voconces, was worshipped by the people of Boudicca with human sacrifices, like the native Bellona of the Scordisci.[125]

A goddess of the chase was identified with Artemis in Galatia, where she had a priestess Camma, and also in the west. At the feast of the Galatian goddess dogs were crowned with flowers, her worshippers feasted and a sacrifice was made to her, feast and sacrifice being provided out of money laid aside for every animal taken in the chase.[126] Other goddesses were equated with Diana, and one of her statues was destroyed in Christian times at Treves.[127] These goddesses may have been thought of as rushing through the forest with an attendant train, since in later times Diana, with whom they were completely assimilated, became, like Holda, the leader of the “furious host” and also of witches’ revels.[128] The Life of Caesarius of Arles speaks of a “demon” called Diana by the rustics. A bronze statuette represents the goddess riding a wild boar,[129] her symbol and, like herself, a creature of the forest, but at an earlier time itself a divinity of whom the goddess became the anthropomorphic form.

Goddesses, the earlier spirits of the waters, protected rivers and springs, or were associated with gods of healing wells. Dirona or Sirona is associated with Grannos mainly in Eastern Gaul and the Rhine provinces, and is sometimes represented carrying grapes and grain.[130] Thus this goddess may once have been connected with fertility, perhaps an Earth-mother, and if her name means “the long-lived,”[131] this would be an appropriate title for an Earth-goddess. Another goddess, Stanna, mentioned in an inscription at Perigueux, is perhaps “the standing or abiding one,” and thus may also have been Earth-goddess.[132] Grannos was also associated with the local goddesses Vesunna and Aventia, who gave their names to Vesona and Avanche. His statue also stood in the temple of the goddess of the Seine, Sequana.[133] With Bormo were associated Bormana in Southern Gaul, and Damona in Eastern Gaul—perhaps an animal goddess, since the root of her name occurs in Irish dam, “ox,” and Welsh dafad, “sheep.” Dea Brixia was the consort of Luxovius, god of the waters of Luxeuil. Names of other goddesses of the waters are found on ex votos and plaques which were placed in or near them. The Roman Nymphae, sometimes associated with Bormo, were the equivalents of the Celtic water-goddesses, who survived in the water-fairies of later folk-belief. Some river-goddesses gave their names to many rivers in the Celtic area—the numerous Avons being named from Abnoba, goddess of the sources of the Danube, and the many Dees and Dives from Divona. Clota was goddess of the Clyde, Sabrina had her throne “beneath the translucent wave” of the Severn, Icauna was goddess of the Yonne, Sequana of the Seine, and Sinnan of the Shannon.

In some cases forests were ruled by goddesses—that of the Ardennes by Dea Arduinna, and the Black Forest, perhaps because of the many waters in it, by Dea Abnoba.[134] While some goddesses are known only by being associated with a god, e.g. Kosmerta with Mercury in Eastern Gaul, others have remained separate, like Epona, perhaps a river-goddess merged with an animal divinity, and known from inscriptions as a horse-goddess.[135] But the most striking instance is found in the grouped goddesses.

Of these the Deoe Matres, whose name has taken a Latin form and whose cult extended to the Teutons, are mentioned in many inscriptions all over the Celtic area, save in East and North-West Gaul.[136] In art they are usually represented as three in number, holding fruit, flowers, a cornucopia, or an infant. They were thus goddesses of fertility, and probably derived from a cult of a great Mother-goddess, the Earth personified. She may have survived as a goddess Berecynthia; worshipped at Autun, where her image was borne through the fields to promote fertility, or as the goddesses equated with Demeter and Kore, worshipped by women on an island near Britain.[137] Such cults of a Mother-goddess lie behind many religions, but gradually her place was taken by an Earth-god, the Celtic Dispater or Dagda, whose consort the goddess became. She may therefore be the goddess with the cornucopia on monuments of the horned god, or Aeracura, consort of Dispater, or a goddess on a monument at Epinal holding a basket of fruit and a cornucopia, and accompanied by a ram’s-headed serpent.[138] These symbols show that this goddess was akin to the Matres. But she sometimes preserved her individuality, as in the case of Berecynthia and the Matres, though it is not quite clear why she should have been thus triply multiplied. A similar phenomenon is found in the close connection of Demeter and Persephone, while the Celts regarded three as a sacred number. The primitive division of the year into three seasons—spring, summer, and winter—may have had its effect in triplicating a goddess of fertility with which the course of the seasons was connected.[139] In other mythologies groups of three goddesses are found, the Hathors in Egypt, the Moirai, Gorgons, and Graiae of Greece, the Roman Fates, and the Norse Nornae, and it is noticeable that the Matres were sometimes equated with the Parcae and Fates.[140]

In the Matres, primarily goddesses of fertility and plenty, we have one of the most popular and also primitive aspects of Celtic religion. They originated in an age when women cultivated the ground, and the Earth was a goddess whose cult was performed by priestesses. But in course of time new functions were bestowed on the Matres. Possibly river-goddesses and others are merely mothers whose functions have become specialised. The Matres are found as guardians of individuals, families, houses, of towns, a province, or a whole nation, as their epithets in inscriptions show. The Matres Domesticae are household goddesses; the Matres Treverae, or Gallaicae, or Vediantae, are the mothers of Treves, of the Gallaecae, of the Vediantii; the Matres Nemetiales are guardians of groves. Besides presiding over the fields as Matres Campestrae they brought prosperity to towns and people.[141] They guarded women, especially in childbirth, as ex votos prove, and in this aspect they are akin to the Junones worshipped also in Gaul and Britain. The name thus became generic for most goddesses, but all alike were the lineal descendants of the primitive Earth-mother.[142]

Popular superstition has preserved the memory of these goddesses in the three bonnes dames, dames blanches, and White Women, met by wayfarers in forests, or in the three fairies or wise women of folk-tales, who appear at the birth of children. But sometimes they have become hateful hags. The Matres and other goddesses probably survived in the beneficent fairies of rocks and streams, in the fairy Abonde who brought riches to houses, or Esterelle of Provence who made women fruitful, or Aril who watched over meadows, or in beings like Melusine, Viviane, and others.[143] In Gallo-Roman Britain the cult of the Matres is found, but how far it was indigenous there is uncertain. A Welsh name for fairies, Y Mamau, “the Mothers,” and the phrase, “the blessing of the Mothers” used of a fairy benediction, may be a reminiscence of such goddesses.[144] The presence of similar goddesses in Ireland will be considered later.[145] Images of the Matres bearing a child have sometimes been taken for those of the Virgin, when found accidentally, and as they are of wood blackened with age, they are known as Vierges Noires, and occupy an honoured place in Christian sanctuaries. Many churches of Notre Dame have been built on sites where an image of the Virgin is said to have been miraculously found—the image probably being that of a pagan Mother. Similarly, an altar to the Matres at Vaison is now dedicated to the Virgin as the “good Mother.”[146]

In inscriptions from Eastern and Cisalpine Gaul, and from the Rhine and Danube region, the Matronae are mentioned, and this name is probably indicative of goddesses like the Matres.[147] It is akin to that of many rivers, e.g. the Marne or Meyrone, and shows that the Mothers were associated with rivers. The Mother river fertilised a large district, and exhibited the characteristic of the whole group of goddesses.

Akin also to the Matres are the Suleviae, guardian goddesses called Matres in a few inscriptions; the Comedovae, whose name perhaps denotes guardianship or power; the Dominae, who watched over the home, perhaps the Dames of mediaeval folk-lore; and the Virgines, perhaps an appellative of the Matres, and significant when we find that virgin priestesses existed in Gaul and Ireland.[148] The Proxumae were worshipped in Southern Gaul, and the Quadriviae, goddesses of cross-roads, at Cherbourg.[149]

Some Roman gods are found on inscriptions without being equated with native deities. They may have been accepted by the Gauls as new gods, or they had perhaps completely ousted similar native gods. Others, not mentioned by Caesar, are equated with native deities, Juno with Clivana, Saturn with Arvalus, and to a native Vulcan the Celts vowed spoils of war.[150] Again, many native gods are not equated with Roman deities on inscriptions. Apart from the divinities of Pyrenaean inscriptions, who may not be Celtic, the names of over 400 native deities, whether equated with Roman gods or not, are known. Some of these names are mere epithets, and most of the gods are of a local character, known here by one name, there by another. Only in a very few cases can it be asserted that a god was worshipped over the whole Celtic area by one name, though some gods in Gaul, Britain, and Ireland with different names have certainly similar functions.[151]

The pantheon of the continental Celts was a varied one. Traces of the primitive agricultural rites, and of the priority of goddesses to gods, are found, and the vaguer aspects of primitive nature worship are seen behind the cult of divinities of sky, sun, thunder, forests, rivers, or in deities of animal origin. We come next to evidence of a higher stage, in divinities of culture, healing, the chase, war, and the underworld. We see divinities of Celtic groups—gods of individuals, the family, the tribe. Sometimes war-gods assumed great prominence, in time of war, or among the aristocracy, but with the development of commerce, gods associated with trade and the arts of peace came to the front.[152] At the same time the popular cults of agricultural districts must have remained as of old. With the adoption of Roman civilisation, enlightened Celts separated themselves from the lower aspects of their religion, but this would have occurred with growing civilisation had no Roman ever entered Gaul. In rural districts the more savage aspects of the cult would still have remained, but that these were entirely due to an aboriginal population is erroneous. The Celts must have brought such cults with them or adopted cults similar to their own wherever they came. The persistence of these cults is seen in the fact that though Christianity modified them, it could not root them out, and in out-of-the-way corners, survivals of the old ritual may still be found, for everywhere the old religion of the soil dies hard.

FOOTNOTES:

[53] Caesar, de Bell. Gall. vi. 17, 18.

[54] Bloch (Lavisse), Hist, de France, i. 2, 419; Reinaoh, BF 13, 23.

[55] Trans. Gaelic Soc. of Inverness, xxvi. p. 411 f.

[56] Vallentin, Les Dieux de la cite des Allobroges, 15; Pliny, HN xxxiv. 7.

[57] These names are Alaunius, Arcecius, Artaius, Arvernorix, Arvernus, Adsmerius, Canetonensis, Clavariatis, Cissonius, Cimbrianus, Dumiatis, Magniacus, Moecus, Toeirenus, Vassocaletus, Vellaunus, Visuoius, Biausius, Cimiacinus, Naissatis. See Holder, s.v.

[58] Rhys, HL 6.

[59] Huebner, vii. 271; CIL iii. 5773.

[60] Lucian, Heracles, 1 f. Some Gaulish coins figure a head to which are bound smaller heads. In one case the cords issue from the mouth (Blanchet, i. 308, 316-317). These may represent Lucian’s Ogmios, but other interpretations have been put upon them. See Robert, RC vii. 388; Jullian, 84.

[61] The epithets and names are Anextiomarus, Belenos, Bormo, Borvo, or Bormanus, Cobledulitavus, Cosmis (?), Grannos, Livicus, Maponos, Mogo or Mogounos, Sianus, Toutiorix, Viudonnus, Virotutis. See Holder, s.v.

[62] Pommerol, Ball. de Soc. d’ant. de Paris, ii. fasc. 4.

[63] See Holder, s.v. Many place-names are derived from Borvo, e.g. Bourbon l’Archambaut, which gave its name to the Bourbon dynasty, thus connected with an old Celtic god.

[64] See p. 102, infra.

[65] Jul. Cap. Maxim. 22; Herodian, viii. 3; Tert. Apol. xxiv. 70;

Auson. Prof. xi. 24.

[66] Stokes derives belinuntia from beljo-, a tree or leaf, Irish bile, US 174.

[67] Holder, s.v.; Stokes, US 197; Rhys, HL 23; see p. 180, infra.

[68] Diod. Sic. ii. 47.

[69] Apoll. Rhod. iv. 609.

[70] Albiorix, Alator, Arixo, Beladonnis, Barrex, Belatucadros, Bolvinnus, Braciaca, Britovis, Buxenus, Cabetius, Camulus, Cariocecius, Caturix, Cemenelus, Cicollius, Carrus, Cocosus, Cociduis, Condatis, Cnabetius, Corotiacus, Dinomogetimarus, Divanno, Dunatis, Glarinus, Halamardus, Harmogius, Ieusdriuus, Lacavus, Latabius, Leucetius, Leucimalacus, Lenus, Mullo, Medocius, Mogetius, Nabelcus, Neton, Ocelos, Ollondios, Rudianus, Rigisamus, Randosatis, Riga, Segomo, Sinatis, Smertatius, Toutates, Tritullus, Vesucius, Vincius, Vitucadros, Vorocius. See Holder, s.v.

[71] D’Arbois, ii. 215; Rhys, HL 37.

[72] So Rhys, HL 42.

[73] Huebner, 61.

[74] Holder, s.v.; Lucan, i. 444 f. The opinions of writers who take this view are collected by Reinach, RC xviii. 137.

[75] Holder, s.v. The Gaulish name Camulogenus, “born of Cumel,” represents the same idea as in Fionn’s surname, MacCumall.

[76] Athen. iv. 36; Dioscorides, ii. 110; Joyce, SH ii. 116, 120; IT i. 437, 697.

[77] Pliny, HN xviii. 7.

[78] Gaidoz, Le Dieu Gaulois de Soleil; Reinach, CS 98, BF 35; Blanchet, i. 27.

[79] Lucan, Phar. i. 444. Another form, Tanaros, may be simply the German Donar.

[80] Loth, i. 270.

[81] Gaidoz, RC vi. 457; Reinach, OS 65, 138; Blanchet, i. 160. The hammer is also associated with another Celtic Dispater, equated with Sylvanus, who was certainly not a thunder-god.

[82] Reinach, BF 137 f.; Courcelle-Seneuil, 115 f.

[83] Barthelemy, RC i. l f.

[84] See Flouest, Rev. Arch. v. 17.

[85] Reinach, RC xvii. 45.

[86] D’Arbois, ii. 126. He explains Nantosvelta as meaning “She who is brilliant in war.” The goddess, however, has none of the attributes of a war-goddess. M. D’Arbois also saw in a bas-relief of the hammer-god, a female figure, and a child, the Gaulish equivalents of Balor, Ethne, and Lug (RC xv. 236). M. Reinach regards Sucellos, Nantosvelta, and a bird which is figured with them, as the same trio, because pseudo-Plutarch (de Fluv. vi. 4) says that lougos means “crow” in Celtic. This is more than doubtful. In any case Ethne has no warlike traits in Irish story, and as Lug and Balor were deadly enemies, it remains to be explained why they appear tranquilly side by side. See RC xxvi. 129. Perhaps Nantosvelta, like other Celtic goddesses, was a river nymph. Nanto Gaulish is “valley,” and nant in old Breton is “gorge” or “brook.” Her name might mean “shining river.” See Stokes, US 193, 324.

[87] RC xviii. 254. Cernunnos may be the Juppiter Cernenos of an inscription from Pesth, Holder, s.v.

[88] Reinach, BF 186, fig. 177.

[89] Rev. Arch. xix. 322, pl. 9.

[90] Bertrand, Rev. Arch. xv. 339, xvi. pl. 12.

[91] Ibid. xv. pl. 9, 10.

[92] Ibid. xvi. 9.

[93] Ibid. pl. 12 bis.

[94] Bertrand, Rev. Arch. xvi. 8.

[95] Ibid. xvi. 10 f.

[96] Ibid. xv., xvi.; Reinach, BF 17, 191.

[97] Bull. Epig. i. 116; Strabo, iv. 3; Diod. Sic. v. 28.

[98] Diod. Sic. v. 30; Reinach, BF 193.

[99] See p. 212, infra.

[100] See p. 166, infra.

[101] See, e.g., Mowat, Bull. Epig. i. 29; de Witte, Rev. Arch. ii. 387, xvi. 7; Bertrand, ibid. xvi. 3.

[102] See pp. 102, 242, infra; Joyce, SH ii. 554; Curtin, 182; RC xxii. 123, xxiv. 18.

[103] Dom Martin, ii. 185; Reinach, BF 192, 199.

[104] See, however, p. 136, infra; and for another interpretation of this god as equivalent of the Irish Lug slaying Balor, see D’Arbois, ii. 287.

[105] See p. 229, infra.

[106] Reinach, BF 162, 184; Mowat, Bull. Epig. i. 62, Rev. Epig. 1887, 319, 1891, 84.

[107] Reinach, BF 141, 153, 175, 176, 181; see p. 218, infra. Flouest, Rev. Arch. 1885, i. 21, thinks that the identification was with an earlier chthonian Silvanus. Cf. Jullian, 17, note 3, who observes that the Gallo-Roman assimilations were made “sur le doinaine archaisant des faits populaires et rustiques de l’Italie.” For the inscriptions, see Holder, s.v.

[108] Stokes, US 302; MacBain, 274; RC xxvi. 282.

[109] Gaidoz, Rev. Arch. ii. 1898; Mowat, Bull. Epig. i. 119; Courcelle-Seneuil, 80 f.; Pauly-Wissowa, Real. Lex. i. 667; Daremberg-Saglio, Dict. ii., s.v. “Dispater.”

[110] Lucan, i. 444; RC xviii. 254, 258.

[111] See p. 127, infra.

[112] For a supposed connection between this bas-relief and the myth of Geryon, see Reinach, BF 120; RC xviii. 258 f.

[113] Coins of the Ancient Britons, 386; Holder, i. 1475, 1478.

[114] For these theories see Dom Martin, ii. 2; Bertrand, 335 f.

[115] Cf. Reinach, RC xviii. 149.

[116] Orelli, 2107, 2072; Monnier, 532; Tacitus, xxi. 38.

[117] Holder, i. 824; Reinach, Rev. Arch. xx. 262; D’Arbois, Les

Celtes, 20. Other grouped gods are the Bacucei, Castoeci, Icotii,

Ifles, Lugoves, Nervini, and Silvani. See Holder, s.v.

[118] For all these see Holder, s.v.

[119] Professor Anwyl gives the following statistics: There are 35 goddesses mentioned once, 2 twice, 3 thrice, 1 four times, 2 six times, 2 eleven times, 1 fourteen times (Sirona), 1 twenty-one times (Rosmerta), 1 twenty-six times (Epona) (Trans. Gael. Soc. Inverness, xxvi. 413).

[120] Caesar, vi. 17.

[121] D’Arbois, Les Celtes, 54; Rev. Arch. i. 201. See Holder, s.v.

[122] Solinus, xxii. 10; Holder, s.v.

[123] Ptolemy, ii. 2.

[124] See p. 71, infra.

[125] Dio Cass. lxii. 7; Amm. Mare, xxvii. 4. 4.

[126] Plutarch, de Vir. Mul. 20; Arrian, Cyneg. xxxiv. 1.

[127] S. Greg. Hist. viii. 15.

[128] Grimm, Teut. Myth. 283, 933; Reinach, RC xvi. 261.

[129] Reinach, BF 50.

[130] Holder, i. 1286; Robert, RC iv. 133.

[131] Rhys, HL 27.

[132] Anwyl, Celt. Rev. 1906, 43.

[133] Holder, s.v.; Bulliot, RC ii. 22.

[134] Holder, i. 10, 89.

[135] Holder, s.v.; see p. 213, infra.

[136] Holder, ii. 463. They are very numerous in South-East Gaul, where also three-headed gods are found.

[137] See pp. 274-5, infra.

[138] Courcelle-Seneuil, 80-81.

[139] See my article “Calendar” in Hastings’ Encyclop. of Religion and Ethics, iii. 80.

[140] CIL v. 4208, 5771, vii. 927; Holder, ii. 89.

[141] For all these titles see Holder, s.v.

[142] There is a large literature devoted to the Matres. See De Wal, Die Maeder Gottinem; Vallentin, Le Culte des Matrae; Daremberg-Saglio, Dict. s.v. Matres; Ihm, Jahrbuch. des Vereins von Alterth. in Rheinlande, No. 83; Roscher, Lexicon, ii. 2464 f.

[143] See Maury, Fees du Moyen Age; Sebillot, i. 262; Monnier, 439 f.; Wright, Celt, Roman, and Saxon, 286 f.; Vallentin, RC iv. 29. The Matres may already have had a sinister aspect in Roman times, as they appear to be intended by an inscription Lamiis Tribus on an altar at Newcastle. Huebner, 507.

[144] Anwyl, Celt. Rev. 1906, 28. Cf. Y Foel Famau, “the hill of the Mothers,” in the Clwydian range.

[145] See p. 73, infra.

[146] Vallentin, op. cit. iv. 29; Maury, Croyances du Moyen Age, 382.

[147] Holder, s.v.

[148] See pp. 69, 317, infra.

[149] For all these see Holder, s.v.; Rhys, HL 103; RC iv. 34.

[150] Florus, ii. 4.

[151] See the table of identifications, p. 125, infra.

[152] We need not assume with Jullian, 18, that there was one supreme god, now a war-god, now a god of peace. Any prominent god may have become a war-god on occasion.