Quaker Furniture

[This is taken from Thomas Clarkson’s A Portraiture of Quakerism.]

[This is taken from Thomas Clarkson’s A Portraiture of Quakerism.]

Quakers are in the use of plain furniture—this usage founded on principles, similar to those on dress—this usage general—Quakers have seldom paintings, prints, or portraits in their houses, as, articles of furniture—reasons for their disuse of such articles.

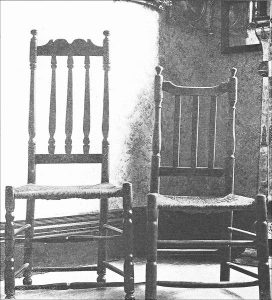

As the Quakers are found in the use of garments, differing from those of others in their shape and fashion, and in the graveness of their color, and in the general plainness of their appearance, so they are found in the use of plain and frugal furniture in their houses.

The custom of using plain furniture has not arisen from the circumstance, that any particular persons in the society, estimable for their lives and characters, have set the example in their families, but from the principles of the Quaker-constitution itself. It has arisen from principles similar to those, which dictated the continuance of the ancient Quaker-dress. The choice of furniture, like the choice of clothes, is left to be adjudged by the rules of decency and usefulness, but never by the suggestions of show. The adoption of taste, instead of utility, in this case, would be considered as a conscious conformity with the fashions of the world. Splendid furniture also would be considered as pernicious as splendid clothes. It would be classed with external ornaments, and would be reckoned equally productive of pride, with these. The custom therefore of plainness in the articles of domestic use is pressed upon all Quakers: and that the subject may not be forgotten, it is incorporated in their religious discipline; in consequence of which, it is held forth to their notice, in a public manner, in all the monthly and quarterly meetings of the kingdom, and in all the preparative meetings, at least once in the year.

It may be admitted as a truth, that the society practice, with few exceptions, what is considered to be the proper usage on such occasions. The poor, we know, cannot use any but homely-furniture. The middle clashes are universally in such habits. As to the rich, there is a difference in the practice of these. Some, and indeed many of them, use as plain and frugal furniture, as those in moderate circumstances. Others again step beyond the practice of the middle classes, and buy what is more costly, not with a view of show, so much as to accommodate their furniture to the size and goodness of their houses. In the houses of others again, who have more than ordinary intercourse with the world, we now and then see what is elegant, but seldom what would be considered to be extravagant furniture. We see no chairs with satin bottoms and gilded frames, no magnificent pier-glasses, no superb chandeliers, no curtains with extravagant trimmings. At least, in all my intercourse with the Quakers, I have never observed such things. If there are persons in the society, who use them, they must be few in number, and these must be conscious that, by the introduction of such finery into their houses, they are going against the advices annually given them in their meetings on this subject, and that they are therefore violating the written law, as well as departing from the spirit of Quakerism.

But if these or similar principles are adopted by the society on this subject, it must be obvious, that in walking through the rooms of the Quakers, we shall look in vain for some articles that are classed among the furniture of other people. We shall often be disappointed, for instance, if we expect to find either paintings or prints in frame. I seldom remember to have seen above three or four articles of this description in all my intercourse with the Quakers. Some families had one of these, others a second, and others a third, but none had them all. And in many families neither the one nor the other was to be seen.

One of the prints, to which I allude, contained a representation of the conclusion of the famous treaty between William Penn and the Indians of America. This transaction every body knows, afforded, in all its circumstances, a proof to the world, of the singular honor and uprightness of those ancestors of the Quakers who were concerned in it. The Indians too entertained an opinion no less favorable of their character, for they handed down the memory of the event under such impressive circumstances, that their descendants have a particular love for the character, and a particular reliance on the word, of a Quaker at the present day. The print alluded to was therefore probably hung up as the pleasing record of a transaction, so highly honorable to the principles of the society; where knowledge took no advantage of ignorance, but where she associated herself with justice, that she might preserve the balance equal. “This is the only treaty,” says a celebrated writer, “between the Indians and the Christians, that was never ratified by an oath, and was never broken.”

The second was a print of a slave-ship, published a few years ago, when the circumstances of the slave-trade became a subject of national inquiry. In this the oppressed Africans are represented, as stowed in different parts according to the number transported and to the scale of the dimensions of the vessel. This subject could not be indifferent to those, who had exerted themselves as a body for the annihilation of this inhuman traffic. The print, however, was not hung up by the Quakers, either as a monument of what they had done themselves, or as a stimulus to farther exertion on the same subject, but, I believe, from the pure motive of exciting benevolence; of exciting the attention of those, who should come into their houses, to the case of the injured Africans, and of procuring sympathy in their favor.

The third contained a plan of the building of Ackworth-school. This was hung up as a descriptive view of a public seminary, instituted and kept up by the subscription and care of the society at large.

But though all the prints, that have been mentioned, were hung up in frames on the motives severally assigned to them, no others were to be seen as their companions. It is in short not the practice of the society to decorate their houses in this manner.

Prints in frames, if hung up promiscuously in a room, would be considered as ornamental furniture, or as furniture for show. They would therefore come under the denomination of superfluities; and the admission of such, in the way that other people admit them would be considered as an adoption of the empty customs or fashions of the world.

But though the Quakers are not in the practice of hanging up prints in frames, yet there are amateurs among them, who have a number and variety of prints in their possession. But these appear chiefly in collections, bound together in books, or preserved in book covers, and not in frames as ornamental furniture for their rooms. These amateurs, however, are but few in number. The Quakers have in general only a plain and useful education. They are not brought up to admire such things, and they have therefore in general but little taste for the fine and masterly productions of the painters’ art.

Neither would a person, in going through the houses of the Quakers, find any portraits either of themselves, or of any of their families, or ancestors, except, to the latter case, they had been taken before they became Quakers. The first Quakers never had their portraits taken with their own knowledge and consent. Considering themselves as poor and helpless creatures, and little better than dust and ashes, they had but a mean idea of their own images. They were of opinion also, that pride and self-conceit would be likely to arise to men from the view, and ostentatious parade, of their own persons. They considered also, that it became them, as the founders of the society, to bear their testimony against the vain and superfluous fashions of the world. They believed also, if there were those whom they loved, that the best method of showing their regard to these would be not by having their fleshly images before their eyes, but by preserving their best actions in their thoughts, as worthy of imitation; and that their own memory, in the same manner, should be perpetuated rather in the loving hearts, and kept alive in the edifying conversation of their descendants, than in the perishing tablets of canvas, fixed upon the walls of their habitations. Hence no portraits are to be seen of many of those great and eminent men in the society, who are now mingled with the dust.

These ideas, which thus actuated the first Quakers on this subject, are those of the Quakers as a body at the present day. There may be here and there an individual, who has had a portrait of some of his family taken. But such instances may be considered as rare exceptions from the general rule. In no society is it possible to establish maxims, which shall influence an universal practice.