Tuatha de Danann

By J. A. MacCulloch

By J. A. MacCulloch

The meaning formerly given to Tuatha De Danann was “the men of science who were gods,” danann being here connected with dan, “knowledge.” But the true meaning is “the tribes or folk of the goddess Danu,”[199] which agrees with the cognates Tuatha or Fir Dea, “tribes or men of the goddess.” The name was given to the group, though Danu had only three sons, Brian, Iuchar, and Iucharbar. Hence the group is also called fir tri ndea, “men of the three gods.”[200] The equivalents in Welsh story of Danu and her folk are Don and her children. We have seen that though they are described as kings and warriors by the annalists, traces of their divinity appear. In the Cuchulainn cycle they are supernatural beings and sometimes demons, helping or harming men, and in the Fionn cycle all these characteristics are ascribed to them.

But the theory which prevailed most is that which connected them with the hills or mounds, the last resting-places of the mighty dead. Some of these bore their names, while other beings were also associated with the mounds (sid)–Fomorians and Milesian chiefs, heroes of the sagas, or those who had actually been buried in them.[201] Legend told how, after the defeat of the gods, the mounds were divided among them, the method of division varying in different versions. In an early version the Tuatha De Danann are immortal and the Dagda divides the sid.[202] But in a poem of Flann Manistrech (ob. 1056) they are mortals and die.[203] Now follows a regular chronology giving the dates of their reigns and their deaths, as in the poem of Gilla Coemain (eleventh century).[204] Hence another legend told how, Dagda being dead, Bodb Dearg divided the sid, yet even here Manannan is said to have conferred immortality upon the Tuatha De Danann.[205] The old pagan myths had shown that gods might die, while in ritual their representatives were slain, and this may have been the starting-point of the euhemerising process.

But the divinity of the Tuatha De Danann is still recalled. Eochaid O’Flynn (tenth century), doubtful whether they are men or demons, concludes, “though I have treated of these deities in order, yet have I not adored them.”[206] Even in later times they were still thought of as gods in exile, a view which appears in the romantic tales and sagas existing side by side with the notices of the annalists. They were also regarded as fairy kings and queens, and yet fairies of a different order from those of ordinary tradition. They are “fairies or sprites with corporeal forms, endowed with immortality,” and yet also dei terreni or side worshipped by the folk before the coming of S. Patrick. Even the saint and several bishops were called by the fair pagan daughters of King Loegaire, fir side, “men of the sid,” that is, gods.[207] The sid were named after the names of the Tuatha De Danann who reigned in them, but the tradition being localised in different places, several mounds were sometimes connected with one god. The sid were marvellous underground palaces, full of strange things, and thither favoured mortals might go for a time or for ever. In this they correspond exactly to the oversea Elysium, the divine land.

But why were the Tuatha De Danann associated with the mounds? If fairies or an analogous race of beings were already in pagan times connected with hills or mounds, gods now regarded as fairies would be connected with them. Dr. Joyce and O’Curry think that an older race of aboriginal gods or sid-folk preceded the Tuatha Dea in the mounds.[208] These may have been the Fomorians, the “champions of the sid,” while in Mesca Ulad the Tuatha Dea go to the underground dwellings and speak with the side already there. We do not know that the fairy creed as such existed in pagan times, but if the side and the Tuatha De Danann were once distinct, they were gradually assimilated. Thus the Dagda is called “king of the side”; Aed Abrat and his daughters, Fand and Liban, and Labraid, Liban’s husband, are called side, and Manannan is Fand’s consort.[209] Labraid’s island, like the sid of Mider and the land to which women of the side invite Connla, differs but little from the usual divine Elysium, while Mider, one of the side, is associated with the Tuatha De Danann.[210] The side are once said to be female, and are frequently supernatural women who run away or marry mortals.[211] Thus they may be a reminiscence of old Earth goddesses. But they are not exclusively female, since there are kings of the side, and as the name Fir side, “men of the side,” shows, while S. Patrick and his friends were taken for sid-folk.

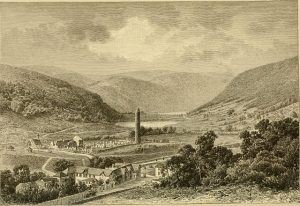

The formation of the legend was also aided by the old cult of the gods on heights, some of them sepulchral mounds, and now occasionally sites of Christian churches.[212] The Irish god Cenn Cruaich and his Welsh equivalent Penn Cruc, whose name survives in Pennocrucium, have names meaning “chief or head of the mound.”[213] Other mounds or hills had also a sacred character. Hence gods worshipped at mounds, dwelling or revealing themselves there, still lingered in the haunted spots; they became fairies, or were associated with the dead buried in the mounds, as fairies also have been, or were themselves thought to have died and been buried there. The haunting of the mounds by the old gods is seen in a prayer of S. Columba’s, who begs God to dispel “this host (i.e. the old gods) around the cairns that reigneth.”[214] An early MS also tells how the Milesians allotted the underground part of Erin to the Tuatha Dea who now retired within the hills; in other words, they were gods of the hills worshipped by the Milesians on hills.[215] But, as we shall see, the gods dwelt elsewhere than in hills.[216]

Tumuli may already in pagan times have been pointed out as tombs of gods who died in myth or ritual, like the tombs of Zeus in Crete and of Osiris in Egypt. Again, fairies, in some aspects, are ghosts of the dead, and haunt tumuli; hence, when gods became fairies they would do the same. And once they were thought of as dead kings, any notable tumuli would be pointed out as theirs, since it is a law in folk-belief to associate tumuli or other structures not with the dead or with their builders, but with supernatural or mythical or even historical personages. If side ever meant “ghosts,” it would be easy to call the dead gods by this name, and to connect them with the places of the dead.[217]

Many strands went to the weaving of the later conception of the gods, but there still hung around them an air of mystery, and the belief that they were a race of men was never consistent with itself.

Danu gave her name to the whole group of gods, and is called their mother, like the Egyptian Neith or the Semitic Ishtar.[218] In the annalists she is daughter of Dagda, and has three sons. She may be akin to the goddess Anu, whom Cormac describes as “mater deorum hibernensium. It was well she nursed the gods.” From her name he derives ana, “plenty,” and two hills in Kerry are called “the Paps of Anu.”[219] Thus as a goddess of plenty Danu or Anu may have been an early Earth-mother, and what may be a dim memory of Anu in Leicestershire confirms this view. A cave on the Dane Hills is called “Black Annis’ Bower,” and she is said to have been a savage woman who devoured human victims.[220] Earth-goddesses usually have human victims, and Anu would be no exception. In the cult of Earth divinities Earth and under-Earth are practically identical, while Earth-goddesses like Demeter and Persephone were associated with the underworld, the dead being Demeter’s folk. The fruits of the earth with their roots below the surface are then gifts of the earth- or under-earth goddess. This may have been the case with Danu, for in Celtic belief the gifts of civilisation came from the underworld or from the gods. Professor Rhys finds the name Anu in the dat. Anoniredi, “chariot of Anu,” in an inscription from Vaucluse, and the identification is perhaps established by the fact that goddesses of fertility were drawn through the fields in a vehicle.[221] Cormac also mentions Buanann as mother and nurse of heroes, perhaps a goddess worshipped by heroes.[222]

Danu is also identified with Brigit, goddess of knowledge (dan), perhaps through a folk-etymology. She was worshipped by poets, and had two sisters of the same name connected with leechcraft and smithwork.[223] They are duplicates or local forms of Brigit, a goddess of culture and of poetry, so much loved by the Celts. She is thus the equivalent of the Gaulish goddess equated with Minerva by Caesar, and found on inscriptions as Minerva Belisama and Brigindo. She is the Dea Brigantia of British inscriptions.[224] One of the seats of her worship was the land of the Brigantes, of whom she was the eponymous goddess, and her name (cf. Ir. brig, “power” or “craft”; Welsh bri, “honour,” “renown”) suggests her high functions. But her popularity is seen in the continuation of her personality and cult in those of S. Brigit, at whose shrine in Kildare a sacred fire, which must not be breathed on, or approached by a male, was watched daily by nineteen nuns in turn, and on the twentieth day by the saint herself.[225] Similar sacred fires were kept up in other monasteries,[226] and they point to the old cult of a goddess of fire, the nuns being successors of a virgin priesthood like the vestals, priestesses of Vesta. As has been seen, the goddesses Belisama and Sul, probably goddesses of fire, resembled Brigit in this.[227] But Brigit, like Vesta, was at once a goddess of fire and of fertility, as her connection with Candlemas and certain ritual survivals also suggest. In the Hebrides on S. Bride’s day (Candlemas-eve) women dressed a sheaf of oats in female clothes and set it with a club in a basket called “Briid’s bed.” Then they called, “Briid is come, Briid is welcome.” Or a bed was made of corn and hay with candles burning beside it, and Bride was invited to come as her bed was ready. If the mark of the club was seen in the ashes, this was an omen of a good harvest and a prosperous year.[228] It is also noteworthy that if cattle cropped the grass near S. Brigit’s shrine, next day it was as luxuriant as ever.

Brigit, or goddesses with similar functions, was regarded by the Celts as an early teacher of civilisation, inspirer of the artistic, poetic, and mechanical faculties, as well as a goddess of fire and fertility. As such she far excelled her sons, gods of knowledge. She must have originated in the period when the Celts worshipped goddesses rather than gods, and when knowledge—leechcraft, agriculture, inspiration—were women’s rather than men’s. She had a female priesthood, and men were perhaps excluded from her cult, as the tabued shrine at Kildare suggests. Perhaps her fire was fed from sacred oak wood, for many shrines of S. Brigit were built under oaks, doubtless displacing pagan shrines of the goddess.[229] As a goddess, Brigit is more prominent than Danu, also a goddess of fertility, even though Danu is mother of the gods.

Other goddesses remembered in tradition are Cleena and Vera, celebrated in fairy and witch lore, the former perhaps akin to a river-goddess Clota, the Clutoida (a fountain-nymph) of the continental Celts; the latter, under her alternative name Dirra, perhaps a form of a goddess of Gaul, Dirona.[230] Aine, one of the great fairy-queens of Ireland, has her seat at Knockainy in Limerick, where rites connected with her former cult are still performed for fertility on Midsummer eve. If they were neglected she and her troops performed them, according to local legend.[231] She is thus an old goddess of fertility, whose cult, even at a festival in which gods were latterly more prominent, is still remembered. She is also associated with the waters as a water-nymph captured for a time as a fairy-bride by the Earl of Desmond.[232] But older legends connect her with the sid. She was daughter of Eogabal, king of the sid of Knockainy, the grass on which was annually destroyed at Samhain by his people, because it had been taken from them, its rightful owners. Oilill Olomm and Ferchus resolved to watch the sid on Samhain-eve. They saw Eogabal and Aine emerge from it. Ferchus killed Eogabal, and Oilill tried to outrage Aine, who bit the flesh from his ear. Hence his name of “Bare Ear.”[233] In this legend we see how earlier gods of fertility come to be regarded as hostile to growth. Another story tells of the love of Aillen, Eogabal’s son, for Manannan’s wife and that of Aine for Manannan. Aine offered her favours to the god if he would give his wife to her brother, and “the complicated bit of romance,” as S. Patrick calls it, was thus arranged.[234]

Although the Irish gods are warriors, and there are special war-gods, yet war-goddesses are more prominent, usually as a group of three—Morrigan, Neman, and Macha. A fourth, Badb, sometimes takes the place of one of these, or is identical with Morrigan, or her name, like that of Morrigan, may be generic.[235] Badb means “a scald-crow,” under which form the war-goddesses appeared, probably because these birds were seen near the slain. She is also called Badbcatha, “battle-Badb,” and is thus the equivalent of -athubodua, or, more probably, Cathubodua, mentioned in an inscription from Haute-Savoie, while this, as well as personal names like Boduogenos, shows that a goddess Bodua was known to the Gauls.[236] The badb or battle-crow is associated with the Fomorian Tethra, but Badb herself is consort of a war-god Net, one of the Tuatha De Danann, who may be the equivalent of Neton, mentioned in Spanish inscriptions and equated with Mars. Elsewhere Neman is Net’s consort, and she may be the Nemetona of inscriptions, e.g. at Bath, the consort of Mars. Cormac calls Net and Neman “a venomous couple,” which we may well believe them to have been.[237] To Macha were devoted the heads of slain enemies, “Macha’s mast,” but she, according to the annalists, was slain at Mag-tured, though she reappears in the Cuchulainn saga as the Macha whose ill-treatment led to the “debility” of the Ulstermen.[238] The name Morrigan may mean “great queen,” though Dr. Stokes, connecting mor with the same syllable in “Fomorian,” explains it as “nightmare-queen.”[239] She works great harm to the Fomorians at Mag-tured, and afterwards proclaims the victory to the hills, rivers, and fairy-hosts, uttering also a prophecy of the evils to come at the end of time.[240] She reappears prominently in the Cuchulainn saga, hostile to the hero because he rejects her love, yet aiding the hosts of Ulster and the Brown Bull, and in the end trying to prevent the hero’s death.[241]

Although the Irish gods are warriors, and there are special war-gods, yet war-goddesses are more prominent, usually as a group of three—Morrigan, Neman, and Macha. A fourth, Badb, sometimes takes the place of one of these, or is identical with Morrigan, or her name, like that of Morrigan, may be generic.[235] Badb means “a scald-crow,” under which form the war-goddesses appeared, probably because these birds were seen near the slain. She is also called Badbcatha, “battle-Badb,” and is thus the equivalent of -athubodua, or, more probably, Cathubodua, mentioned in an inscription from Haute-Savoie, while this, as well as personal names like Boduogenos, shows that a goddess Bodua was known to the Gauls.[236] The badb or battle-crow is associated with the Fomorian Tethra, but Badb herself is consort of a war-god Net, one of the Tuatha De Danann, who may be the equivalent of Neton, mentioned in Spanish inscriptions and equated with Mars. Elsewhere Neman is Net’s consort, and she may be the Nemetona of inscriptions, e.g. at Bath, the consort of Mars. Cormac calls Net and Neman “a venomous couple,” which we may well believe them to have been.[237] To Macha were devoted the heads of slain enemies, “Macha’s mast,” but she, according to the annalists, was slain at Mag-tured, though she reappears in the Cuchulainn saga as the Macha whose ill-treatment led to the “debility” of the Ulstermen.[238] The name Morrigan may mean “great queen,” though Dr. Stokes, connecting mor with the same syllable in “Fomorian,” explains it as “nightmare-queen.”[239] She works great harm to the Fomorians at Mag-tured, and afterwards proclaims the victory to the hills, rivers, and fairy-hosts, uttering also a prophecy of the evils to come at the end of time.[240] She reappears prominently in the Cuchulainn saga, hostile to the hero because he rejects her love, yet aiding the hosts of Ulster and the Brown Bull, and in the end trying to prevent the hero’s death.[241]

The prominent position of these goddesses must be connected with the fact that women went out to war—a custom said to have been stopped by Adamnan at his mother’s request, and that many prominent heroines of the heroic cycles are warriors, like the British Boudicca, whose name may be connected with boudi, “victory.” Specific titles were given to such classes of female warriors–bangaisgedaig, banfeinnidi, etc.[242] But it is possible that these goddesses were at first connected with fertility, their functions changing with the growing warlike tendencies of the Celts. Their number recalls that of the threefold Matres, and possibly the change in their character is hinted in the Romano-British inscription at Benwell to the Lamiis Tribus, since Morrigan’s name is glossed lamia.[243] She is also identified with Anu, and is mistress of Dagda, an Earth-god, and with Badb and others expels the Fomorians when they destroyed the agricultural produce of Ireland.[244] Probably the scald-crow was at once the symbol and the incarnation of the war-goddesses, who resemble the Norse Valkyries, appearing sometimes as crows, and the Greek Keres, bird-like beings which drank the blood of the slain. It is also interesting to note that Badb, who has the character of a prophetess of evil, is often identified with the “Washer at the Ford,” whose presence indicates death to him whose armour or garments she seems to cleanse.[245]

The Matres, goddesses of fertility, do not appear by name in Ireland, but the triplication of such goddesses as Morrigan and Brigit, the threefold name of Dagda’s wife, or the fact that Arm, Danu, and Buanan are called “mothers,” while Buanan’s name is sometimes rendered “good mother,” may suggest that such grouped goddesses were not unknown. Later legend knows of white women who assist in spinning, or three hags with power over nature, or, as in the Battle of Ventry, of three supernatural women who fall in love with Conncrithir, aid him in fight, and heal his wounds. In this document and elsewhere is mentioned the “sid of the White Women.”[246] Goddesses of fertility are usually goddesses of love, and the prominence given to females among the side, the fact that they are often called Be find, “White Women,” like fairies who represent the Matres elsewhere, and that they freely offer their love to mortals, may connect them with this group of goddesses. Again, when the Milesians arrived in Ireland, three kings of the Tuatha Dea had wives called Eriu, Banba, and Fotla, who begged that Ireland should be called after them. This was granted, but only Eriu (Erin) remained in general use.[247] The story is an aetiological myth explaining the names of Ireland, but the three wives may be a group like the Matres, guardians of the land which took its name from them.

Brian, Iuchar, and Iucharba, who give a title to the whole group, are called tri dee Donand, “the three gods (sons of) Danu,” or, again, “gods of dan” (knowledge), perhaps as the result of a folk-etymology, associating dan with their mother’s name Danu.[248] Various attributes are personified as their descendants, Wisdom being son of all three.[249] Though some of these attributes may have been actual gods, especially Ecne or Wisdom, yet it is more probable that the personification is the result of the subtleties of bardic science, of which similar examples occur.[250] On the other hand, the fact that Ecne is the son of three brothers, may recall some early practice of polyandry of which instances are met with in the sagas.[251] M. D’Arbois has suggested that Iuchar and Iucharba are mere duplicates of Brian, who usually takes the leading place, and he identifies them with three kings of the Tuatha Dea reigning at the time of the Milesian invasion—

MacCuill, MacCecht, and MacGrainne, so called, according to Keating, because the hazel (coll), the plough (cecht), and the sun (grian) were “gods of worship” to them. Both groups are grandsons of Dagda, and M. D’Arbois regards this second group as also triplicates of one god, because their wives Fotla, Banba, and Eriu all bear names of Ireland itself, are personifications of the land, and thus may be “reduced to unity.”[252] While this reasoning is ingenious, it should be remembered that we must not lay too much stress upon Irish divine genealogies, while each group of three may have been similar local gods associated at a later time as brothers. Their separate personality is suggested by the fact that the Tuatha De Danann are called after them “the Men of the Three Gods,” and their supremacy appears in the incident of Dagda, Lug, and Ogma consulting them before the fight at Mag-tured—a natural proceeding if they were gods of knowledge or destiny.[253] The brothers are said to have slain the god Cian, and to have been themselves slain by Lug, and on this seems to have been based the story of The Children of Tuirenn, in which they perish through their exertions in obtaining the eric demanded by Lug.[254] Here they are sons of Tuirenn, but more usually their mother Danu or Brigit is mentioned.

Another son of Brigit’s was Ogma, master of poetry and inventor of ogham writing, the word being derived from his name.[255] It is more probable that Ogma’s name is a derivative from some word signifying “speech” or “writing,” and that the connection with “ogham” may be a mere folk-etymology. Ogma appears as the champion of the gods,[256] a position given him perhaps from the primitive custom of rousing the warriors’ emotions by eloquent speeches before a battle. Similarly the Babylonian Marduk, “seer of the gods,” was also their champion in fight. Ogma fought and died at Mag-tured; but in other accounts he survives, captures Tethra’s sword, goes on the quest for Dagda’s harp, and is given a sid after the Milesian victory. Ogma’s counterpart in Gaul is Ogmios, a Herakles and a god of eloquence, thus bearing the dual character of Ogma, while Ogma’s epithet grianainech, “of the smiling countenance,” recalls Lucian’s account of the “smiling face” of Ogmios.[257] Ogma’s high position is the result of the admiration of bardic eloquence among the Celts, whose loquacity was proverbial, and to him its origin was doubtless ascribed, as well as that of poetry. The genealogists explain his relationship to the other divinities in different ways, but these confusions may result from the fact that gods had more than one name, of which the annalists made separate personalities. Most usually Ogma is called Brigit’s son. Her functions were like his own, but in spite of the increasing supremacy of gods over goddesses, he never really eclipsed her.

Among other culture gods were those associated with the arts and crafts—the development of Celtic art in metal-work necessitating the existence of gods of this art. Such a god is Goibniu, eponymous god of smiths (Old Ir. goba, “smith”), and the divine craftsman at the battle of Mag-tured, making spears which never failed to kill.[258] Smiths have everywhere been regarded as uncanny—a tradition surviving from the first introduction of metal among those hitherto accustomed to stone weapons and tools. S. Patrick prayed against the “spells of women, smiths, and Druids,” and it is thus not surprising to find that Goibniu had a reputation for magic, even among Christians. A spell for making butter, in an eighth century MS. preserved at S. Gall, appeals to his “science.”[259] Curiously enough, Goibniu is also connected with the culinary art in myth, and, like Hephaistos, prepares the feast of the gods, while his ale preserves their immortality.[260] The elation produced by heady liquors caused them to be regarded as draughts of immortality, like Soma, Haoma, or nectar. Goibniu survives in tradition as the Gobhan Saer, to whom the building of round towers is ascribed.

Another god of crafts was Creidne the brazier (Ir. cerd, “artificer”; cf. Scots caird, “tinker”), who assisted in making a silver hand for Nuada, and supplied with magical rapidity parts of the weapons used at Mag-tured.[261] According to the annalists, he was drowned while bringing golden ore from Spain.[262] Luchtine, god of carpenters, provided spear-handles for the battle, and with marvellous skill flung them into the sockets of the spear-heads.[263]

Diancecht, whose name may mean “swift in power,” was god of medicine, and, with Creidne’s help, fashioned a silver hand for Nuada.[264] His son Miach replaced this by a magic restoration of the real hand, and in jealousy his father slew him—a version of the Maerchen formula of the jealous master. Three hundred and sixty-five herbs grew from his grave, and were arranged according to their properties by his sister Airmed, but Diancecht again confused them, “so that no one knows their proper cures.”[265] At the second battle of Mag-tured, Diancecht presided over a healing-well containing magic herbs. These and the power of spells caused the mortally wounded who were placed in it to recover. Hence it was called “the spring of health.”[266] Diancecht, associated with a healing-well, may be cognate with Grannos. He is also referred to in the S. Gall MS., where his healing powers are extolled.

An early chief of the gods is Dagda, who, in the story of the battle of Mag-tured, is said to be so called because he promised to do more than all the other gods together. Hence they said, “It is thou art the good hand” (dag-dae). The Coir Anmann explains Dagda as “fire of god” (daig and dea). The true derivation is from dagos, “good,” and deivos, “god,” though Dr. Stokes considers Dagda as connected with dagh, whence daghda, “cunning.”[267] Dagda is also called Cera, a word perhaps derived from kar and connected with Lat. cerus, “creator” and other names of his are Ruad-rofhessa, “lord of great knowledge,” and Eochaid Ollathair, “great father,” “for a great father to the Tuatha De Danann was he.”[268] He is also called “a beautiful god,” and “the principal god of the pagans.”[269] After the battle he divides the brugs or sid among the gods, but his son Oengus, having been omitted, by a stratagem succeeded in ousting his father from his sid, over which he now himself reigned[270]–possibly the survival of an old myth telling of a superseding of Dagda’s cult by that of Oengus, a common enough occurrence in all religions. In another version, Dagda being dead, Bodb Dearg divides the sid, and Manannan makes the Tuatha Dea invisible and immortal. He also helps Oengus to drive out his foster-father Elemar from his brug, where Oengus now lives as a god.[271] The underground brugs are the gods’ land, in all respects resembling the oversea Elysium, and at once burial-places of the euhemerised gods and local forms of the divine land. Professor Rhys regards Dagda as an atmospheric god; Dr. MacBain sees in him a sky-god. More probably he is an early Earth-god and a god of agriculture. He has power over corn and milk, and agrees to prevent the other gods from destroying these after their defeat by the Milesians—former beneficent gods being regarded as hurtful, a not uncommon result of the triumph of a new faith.[272] Dagda is called “the god of the earth” “because of the greatness of his power.”[273] Mythical objects associated with him suggest plenty and fertility—his cauldron which satisfied all comers, his unfailing swine, one always living, the other ready for cooking, a vessel of ale, and three trees always laden with fruit. These were in his sid, where none ever tasted death;[274] hence his sid was a local Elysium, not a gloomy land of death, but the underworld in its primitive aspect as the place of gods of fertility. In some myths he appears with a huge club or fork, and M. D’Arbois suggests that he may thus be an equivalent of the Gaulish god with the mallet.[275] This is probable, since the Gaulish god may have been a form of Dispater, an Earth or under-Earth god of fertility.

If Dagda was a god of fertility, he may have been an equivalent of a god whose image was called Cenn or Cromm Cruaich, “Head or Crooked One of the Mound,” or “Bloody Head or Crescent.”[276] Vallancey, citing a text now lost, says that Crom-eocha was a name of Dagda, and that a motto at the sacrificial place at Tara read, “Let the altar ever blaze to Dagda.”[277] These statements may support this identification. The cult of Cromm is preserved in some verses:

“He was their god,

The withered Cromm with many mists…

To him without glory

They would kill their piteous wretched offspring,

With much wailing and peril,

To pour their blood around Cromm Cruaich.Milk and corn

They would ask from him speedily

In return for a third of their healthy issue,

Great was the horror and fear of him.

To him noble Gaels would prostrate themselves.”[278]

Elsewhere we learn that this sacrifice in return for the gifts of corn and milk from the god took place at Samhain, and that on one occasion the violent prostrations of the worshippers caused three-fourths of them to die. Again, “they beat their palms, they pounded their bodies … they shed falling showers of tears.”[279] These are reminiscences of orgiastic rites in which pain and pleasure melt into one. The god must have been a god of fertility; the blood of the victims was poured on the image, the flesh, as in analogous savage rites and folk-survivals, may have been buried in the fields to promote fertility. If so, the victims’ flesh was instinct with the power of the divinity, and, though their number is obviously exaggerated, several victims may have taken the place of an earlier slain representative of the god. A mythic Crom Dubh, “Black Crom,” whose festival occurs on the first Sunday in August, may be another form of Cromm Cruaich. In one story the name is transferred to S. Patrick’s servant, who is asked by the fairies when they will go to Paradise. “Not till the day of judgment,” is the answer, and for this they cease to help men in the processes of agriculture. But in a variant Manannan bids Crom ask this question, and the same result follows.[280] These tales thus enshrine the idea that Crom and the fairies were ancient gods of growth who ceased to help men when they deserted them for the Christian faith. If the sacrifice was offered at the August festival, or, as the texts suggest, at Samhain, after harvest, it must have been on account of the next year’s crop, and the flesh may have been mingled with the seed corn.

Dagda may thus have been a god of growth and fertility. His wife or mistress was the river-goddess, Boand (the Boyne),[281] and the children ascribed to him were Oengus, Bodb Dearg, Danu, Brigit, and perhaps Ogma. The euhemerists made him die of Cethlenn’s venom, long after the battle of Mag-tured in which he encountered her.[282] Irish mythology is remarkably free from obscene and grotesque myths, but some of these cluster round Dagda. We hear of the Gargantuan meal provided for him in sport by the Fomorians, and of which he ate so much that “not easy was it for him to move and unseemly was his apparel,” as well as his conduct with a Fomorian beauty. Another amour of his was with Morrigan, the place where it occurred being still known as “The Couple’s Bed.”[283] In another tale Dagda acts as cook to Conaire the great.[284]

The beautiful and fascinating Oengus is sometimes called Mac Ind Oc, “Son of the Young Ones,” i.e. Dagda and Boand, or In Mac Oc, “The Young Son.” This name, like the myth of his disinheriting his father, may point to his cult superseding that of Dagda. If so, he may then have been affiliated to the older god, as was frequently done in parallel cases, e.g. in Babylon. Oengus may thus have been the high god of some tribe who assumed supremacy, ousting the high god of another tribe, unless we suppose that Dagda was a pre-Celtic god with functions similar to those of Oengus, and that the Celts adopted his cult but gave that of Oengus a higher place. In one myth the supremacy of Oengus is seen. After the first battle of Mag-tured, Dagda is forced to become the slave of Bres, and is much annoyed by a lampooner who extorts the best pieces of his rations. Following the advice of Oengus, he not only causes the lampooner’s death, but triumphs over the Fomorians.[285] On insufficient grounds, mainly because he was patron of Diarmaid, beloved of women, and because his kisses became birds which whispered love thoughts to youths and maidens, Oengus has been called the Eros of the Gaels. More probably he was primarily a supreme god of growth, who occasionally suffered eclipse during the time of death in nature, like Tammuz and Adonis, and this may explain his absence from Mag-tured. The beautiful story of his vision of a maiden with whom he fell violently in love contains too many Maerchen formulae to be of any mythological or religious value. His mother Boand caused search to be made for her, but without avail. At last she was discovered to be the daughter of a semi-divine lord of a sid, but only through the help of mortals was the secret of how she could be taken wrung from him. She was a swan-maiden, and on a certain day only would Oengus obtain her. Ultimately she became his wife. The story is interesting because it shows how the gods occasionally required mortal aid.[286]

Equally influenced by Maerchen formulae is the story of Oengus and Etain. Etain and Fuamnach were wives of Mider, but Fuamnach was jealous of Etain, and transformed her into an insect. In this shape Oengus found her, and placed her in a glass grianan or bower filled with flowers, the perfume of which sustained her. He carried the grianan with him wherever he went, but Fuamnach raised a magic wind which blew Etain away to the roof of Etair, a noble of Ulster. She fell through a smoke-hole into a golden cup of wine, and was swallowed by Etair’s wife, of whom she was reborn.[287] Professor Rhys resolves all this into a sun and dawn myth. Oengus is the sun, Etain the dawn, the grianan the expanse of the sky.[288] But the dawn does not grow stronger with the sun’s influence, as Etain did under that of Oengus. At the sun’s appearance the dawn begins:

“to faint in the light of the sun she loves,

To faint in his light and to die.”

The whole story is built up on the well-known Marchen formulae of the “True Bride” and the “Two Brothers,” but accommodated to well-known mythic personages, and the grianan is the Celtic equivalent of various objects in stories of the “Cinderella” type, in which the heroine conceals herself, the object being bought by the hero and kept in his room.[289] Thus the tale reveals nothing of Etain’s divine functions, but it illustrates the method of the “mythological” school in discovering sun-heroes and dawn-maidens in any incident, mythical or not.

Oengus appears in the Fionn cycle as the fosterer and protector of Diarmaid.[290] With Mider, Bodb, and Morrigan, he expels the Fomorians when they destroy the corn, fruit, and milk of the Tuatha De Danann.[291] This may point to his functions as a god of fertility.

Although Mider appears mainly as a king of the side and ruler of the brug of Bri Leith, he is also connected with the Tuatha Dea.[292] Learning that Etain had been reborn and was now married to King Eochaid, he recovered her from him, but lost her again when Eochaid attacked his brug. He was ultimately avenged in the series of tragic events which led to the death of Eochaid’s descendant Conaire. Though his sid is located in Ireland, it has so much resemblance to Elysium that Mider must be regarded as one of its lords. Hence he appears as ruler of the Isle of Falga, i.e. the Isle of Man regarded as Elysium. Thence his daughter Blathnat, his magical cows and cauldron, were stolen by Cuchulainn and Curoi, and his three cranes from Bri Leith by Aitherne[293]–perhaps distorted versions of the myths which told how various animals and gifts came from the god’s land. Mider may be the Irish equivalent of a local Gaulish god, Medros, depicted on bas-reliefs with a cow or bull.[294]

The victory of the Tuatha Dea at the first battle of Mag-tured, in June, their victory followed, however, by the deaths of many of them at the second battle in November, may point to old myths dramatising the phenomena of nature, and connected with the ritual of summer and winter festivals. The powers of light and growth are in the ascendant in summer; they seem to die in winter. Christian euhemerists made use of these myths, but regarded the gods as warriors who were slain, not as those who die and revive again. At the second battle, Nuada loses his life; at the first, though his forces are victorious, his hand was cut off by the Fomorian Sreng, for even when victorious the gods must suffer. A silver hand was made for him by Diancecht, and hence he was called Nuada Argetlam, “of the silver hand.” Professor Rhys regards him as a Celtic Zeus, partly because he is king of the Tuatha De Danann, partly because he, like Zeus or Tyr, who lost tendons or a hand through the wiles of evil gods, is also maimed.[295] Similarly in the Rig-Veda the Acvins substitute a leg of iron for the leg of Vispala, cut off in battle, and the sun is called “golden-handed” because Savitri cut off his hand and the priests replaced it by one of gold. The myth of Nuada’s hand may have arisen from primitive attempts at replacing lopped-off limbs, as well as from the fact that no Irish king must have any bodily defect, or possibly because an image of Nuada may have lacked a hand or possessed one of silver. Images were often maimed or given artificial limbs, and myths then arose to explain the custom.[296] Nuada appears to be a god of life and growth, but he is not a sun-god. His Welsh equivalent is Llud Llawereint, or “silver-handed,” who delivers his people from various scourges. His daughter Creidylad is to be wedded to Gwythur, but is kidnapped by Gwyn. Arthur decides that they must fight for her yearly on 1st May until the day of judgment, when the victor would gain her hand.[297] Professor Rhys regards Creidylad as a Persephone, wedded alternately to light and dark divinities.[298] But the story may rather be explanatory of such ritual acts as are found in folk-survivals in the form of fights between summer and winter, in which a Queen of May figures, and intended to assist the conflict of the gods of growth with those of blight.[299] Creidylad is daughter of a probable god of growth, nor is it impossible that the story of the battle of Mag-tured is based on mythic explanations of such ritual combats.

The Brythons worshipped Nuada as Nodons in Romano-British times. The remains of his temple exist near the mouth of the Severn, and the god may have been equated with Mars, though certain symbols seem to connect him with the waters as a kind of Neptune.[300] An Irish mythic poet Nuada Necht may be the Nechtan who owned a magic well whence issued the Boyne, and was perhaps a water-god. If such a water-god was associated with Nuada, he and Nodons might be a Celtic Neptune.[301] But the relationship and functions of these various personages are obscure, nor is it certain that Nodons was equated with Neptune or that Nuada was a water-god. His name may be cognate with words meaning “growth,” “possession,” “harvest,” and this supports the view taken here of his functions.[302] The Welsh Nudd Hael, or “the Generous,” who possessed a herd of 21,000 milch kine, may be a memory of this god, and it is possible that, as a god of growth, Nuada had human incarnations called by his name.[303]

Ler, whose name means “sea,” and who was a god of the sea, is father of Manannan as well as of the personages of the beautiful story called The Children of Lir, from which we learn practically all that is known of him. He resented not being made ruler of the Tuatha Dea, but was later reconciled when the daughter of Bodb Dearg was given to him as his wife. On her death, he married her sister, who transformed her step-children into swans.[304] Ler is the equivalent of the Brythonic Llyr, later immortalised by Shakespeare as King Lear.

The greatness of Manannan mac Lir, “son of the sea,” is proved by the fact that he appears in many of the heroic tales, and is still remembered in tradition and folk-tale. He is a sea-god who has become more prominent than the older god of the sea, and though not a supreme god, he must have had a far-spreading cult. With Bodb Dearg he was elected king of the Tuatha De Danann. He made the gods invisible and immortal, gave them magical food, and assisted Oengus in driving out Elemar from his sid. Later tradition spoke of four Manannans, probably local forms of the god, as is suggested by the fact that the true name of one of them is said to be Orbsen, son of Allot. Another, the son of Ler, is described as a renowned trader who dwelt in the Isle of Man, the best of pilots, weather-wise, and able to transform himself as he pleased. The Coir Anmann adds that the Britons and the men of Erin deemed him god of the sea.[305] That position is plainly seen in many tales, e.g. in the magnificent passage of The Voyage of Bran, where he suddenly sweeps into sight, riding in a chariot across the waves from the Land of Promise; or in the tale of Cuchulainn’s Sickness, where his wife Fand sees him, “the horseman of the crested sea,” coming across the waves. In the Agallamh na Senorach he appears as a cavalier breasting the waves. “For the space of nine waves he would be submerged in the sea, but would rise on the crest of the tenth without wetting chest or breast.”[306] In one archaic tale he is identified with a great sea wave which swept away Tuag, while the waves are sometimes called “the son of Lir’s horses”—a name still current in Ireland, or, again, “the locks of Manannan’s wife.”[307] His position as god of the sea may have given rise to the belief that he was ruler of the oversea Elysium, and, later, of the other-world as a magical domain coterminous with this earth. He is still remembered in the Isle of Man, which may owe its name to him, and which, like many another island, was regarded by the Goidels as the island Elysium under its name of Isle of Falga. He is also the Manawyddan of Welsh story.

Manannan appears in the Cuchulainn and Fionn cycles, usually as a ruler of the Other-world. His wife Fand was Cuchulainn’s mistress, Diarmaid was his pupil in fairyland, and Cormac was his guest there. Even in Christian times surviving pagan beliefs caused legend to be busy with his name. King Fiachna was fighting the Scots and in great danger, when a stranger appeared to his wife and announced that he would save her husband’s life if she would consent to abandon herself to him. She reluctantly agreed, and the child of the amour was the seventh-century King Mongan, of whom the annalist says, “every one knows that his real father was Manannan.”[308] Mongan was also believed to be a rebirth of Fionn. Manannan is still remembered in folk-tradition, and in the Isle of Man, where his grave is to be seen, some of his ritual survived until lately, bundles of rushes being placed for him on midsummer eve on two hills.[309] Barintus, who steers Arthur to the fortunate isles, and S. Barri, who crossed the sea on horseback, may have been legendary forms of a local sea-god akin to Manannan, or of Manannan himself.[310] His steed was Enbarr, “water foam or hair,” and Manannan was “the horseman of the maned sea.” “Barintus,” perhaps connected with barr find, “white-topped,” would thus be a surname of the god who rode on Enbarr, the foaming wave, or who was himself the wave, while his mythic sea-riding was transferred to the legend of S. Barri, if such a person ever existed.

Various magical possessions were ascribed to Manannan—his armour and sword, the one making the wearer invulnerable, the other terrifying all who beheld it; his horse and canoe; his swine, which came to life again when killed; his magic cloak; his cup which broke when a lie was spoken; his tablecloth, which, when waved, produced food. Many of these are found everywhere in Maerchen, and there is nothing peculiarly Celtic in them. We need not, therefore, with the mythologists, see in his armour the vapoury clouds or in his sword lightning or the sun’s rays. But their magical nature as well as the fact that so much wizardry is attributed to Manannan, points to a copious mythology clustering round the god, now for ever lost.

The parentage of Lug is differently stated, but that account which makes him son of Cian and of Ethne, daughter of Balor, is best attested.[311] Folk-tradition still recalls the relation of Lug and Balor. Balor, a robber living in Tory Island, had a daughter whose son was to kill her father. He therefore shut her up in an inaccessible place, but in revenge for Balor’s stealing MacIneely’s cow, the latter gained access to her, with the result that Ethne bore three sons, whom Balor cast into the sea. One of them, Lug, was recovered by MacIneely and fostered by his brother Gavida. Balor now slew MacIneely, but was himself slain by Lug, who pierced his single eye with a red-hot iron.[312] In another version, Kian takes MacIneely’s place and is aided by Manannan, in accordance with older legends.[313] But Lug’s birth-story has been influenced in these tales by the Maerchen formula of the girl hidden away because it has been foretold that she will have a son who will slay her father.

Lug is associated with Manannan, from whose land he comes to assist the Tuatha Dea against the Fomorians. His appearance was that of the sun, and by this brilliant warrior’s prowess the hosts were utterly defeated.[314] This version, found in The Children of Tuirenn, differs from the account in the story of Mag-tured. Here Lug arrives at the gates of Tara and offers his services as a craftsman. Each offer is refused, until he proclaims himself “the man of each and every art,” or samildanach, “possessing many arts.” Nuada resigns his throne to him for thirteen days, and Lug passes in review the various craftsmen (i.e. the gods), and though they try to prevent such a marvellous person risking himself in fight, he escapes, heads the warriors, and sings his war-song. Balor, the evil-eyed, he slays with a sling-stone, and his death decided the day against the Fomorians. In this account Lug samildanach is a patron of the divine patrons of crafts; in other words, he is superior to a whole group of gods. He was also inventor of draughts, ball-play, and horsemanship. But, as M. D’Arbois shows, samildanach is the equivalent of “inventor of all arts,” applied by Caesar to the Gallo-Roman Mercury, who is thus an equivalent of Lug.[315] This is attested on other grounds. As Lug’s name appears in Irish Louth (Lug-magh) and in British Lugu-vallum, near Hadrian’s Wall, so in Gaul the names Lugudunum (Lyons), Lugudiacus, and Lugselva (“devoted to Lugus”) show that a god Lugus was worshipped there. A Gaulish feast of Lugus in August—the month of Lug’s festival in Ireland—was perhaps superseded by one in honour of Augustus. No dedication to Lugus has yet been found, but images of and inscriptions to Mercury abound at Lugudunum Convenarum.[316] As there were three Brigits, so there may have been several forms of Lugus, and two dedications to the Lugoves have been found in Spain and Switzerland, one of them inscribed by the shoemakers of Uxama.[317] Thus the Lugoves may have been multiplied forms of Lugus or Lugovos, “a hero,” the meaning given to “Lug” by O’Davoren.[318] Shoe-making was not one of the arts professed by Lug, but Professor Rhys recalls the fact that the Welsh Lleu, whom he equates with Lug, disguised himself as a shoemaker.[319] Lugus, besides being a mighty hero, was a great Celtic culture-god, superior to all other culture divinities.

The euhemerists assigned a definite date to Lug’s death, but side by side with this the memory of his divinity prevailed, and he appears as the father and helper of Cuchulainn, who was possibly a rebirth of the god.[320] His high position appears in the fact that the Gaulish assembly at Lugudunum was held in his honour, like the festival of Lugnasad in Ireland. Craftsmen brought their wares to sell at this festival of the god of crafts, while it may also have been a harvest festival.[321] Whether it was a strictly solar feast is doubtful, though Professor Rhys and others insist that Lug is a sun-god. The name of the Welsh Lleu, “light,” is equated with Lug, and the same meaning assigned to the latter.[322] This equation has been contested and is doubtful, Lugus probably meaning “hero.”[323] Still the sun-like traits ascribed to Lug before Mag-tured suggest that he was a sun-god, and solar gods elsewhere, e.g. the Polynesian Maui, are culture-gods as well. But it should be remembered that Lug is not associated with the true solar festivals of Beltane and Midsummer.

While our knowledge of the Tuatha De Danann is based upon a series of mythic tales and other records, that of the gods of the continental Celts, apart from a few notices in classical authors and elsewhere, comes from inscriptions. But as far as can be judged, though the names of the two groups seldom coincide, their functions must have been much alike, and their origins certainly the same. The Tuatha De Danann were nature divinities of growth, light, agriculture—their symbols and possessions suggesting fertility, e.g. the cauldron. They were divinities of culture and crafts, and of war. There must have been many other gods in Ireland than those described here, while some of those may not have been worshipped all over Ireland. Generally speaking, there were many local gods in Gaul with similar functions but different names, and this may have been true of Ireland. Perhaps the different names given to Dagda, Manannan, and others were simply names of similar local gods, one of whom became prominent, and attracted to himself the names of the others. So, too, the identity of Danu and Brigit might be explained, or the fact that there were three Brigits. We read also in the texts of the god of Connaught, or of Ulster, and these were apparently regional divinities, or of “the god of Druidism”—perhaps a god worshipped specially by Druids.[324] The remote origin of some of these divinities may be sought in the primitive cult of the Earth personified as a fertile being, and in that of vegetation and corn-spirits, and the vague spirits of nature in all its aspects. Some of these still continued to be worshipped when the greater gods had been evolved. Though animal worship was not lacking in Ireland, divinities who are anthropomorphic forms of earlier animal-gods are less in evidence than on the Continent. The divinities of culture, crafts, and war, and of departments of nature, must have slowly assumed the definite personality assigned them in Irish religion. But, doubtless, they already possessed that before the Goidels reached Ireland. Strictly speaking, the underground domain assigned later to the Tuatha De Danann belongs only to such of them as were associated with fertility. But in course of time most of the group, as underground dwellers, were connected with growth and increase. These could be blighted by their enemies, or they themselves could withhold them when their worshippers offended them.[325]

Irish mythology points to the early pre-eminence of goddesses. As agriculture and many of the arts were first in the hands of women, goddesses of fertility and culture preceded gods, and still held their place when gods were evolved. Even war-goddesses are prominent in Ireland. Celtic gods and heroes are often called after their mothers, not their fathers, and women loom largely in the tales of Irish colonisation, while in many legends they play a most important part. Goddesses give their name to divine groups, and, even where gods are prominent, their actions are free, their personalities still clearly defined. The supremacy of the divine women of Irish tradition is once more seen in the fact that they themselves woo and win heroes; while their capacity for love, their passion, their eternal youthfulness and beauty are suggestive of their early character as goddesses of ever-springing fertility.[326]

This supremacy of goddesses is explained by Professor Rhys as non-Celtic, as borrowed by the Celts from the aborigines.[327] But it is too deeply impressed on the fabric of Celtic tradition to be other than native, and we have no reason to suppose that the Celts had not passed through a stage in which such a state of things was normal. Their innate conservatism caused them to preserve it more than other races who had long outgrown such a state of things.

FOOTNOTES:

[199] HL 89; Stokes, RC xii. 129. D’Arbois, ii. 125, explains it as “Folk of the god whose mother is called Danu.”

[200] RC xii. 77. The usual Irish word for “god” is dia; other names are Fiadu, Art, Dess.

[201] See Joyce, SII. i. 252, 262; PN i. 183.

[202] LL 245b.

[203] LL 11.

[204] LL 127. The mounds were the sepulchres of the euhemerised gods.

[205] Book of Fermoy, fifteenth century.

[206] LL 11b.

[207] IT i. 14, 774; Stokes, TL i. 99, 314, 319. Sid is a fairy hill, the hill itself or the dwelling within it. Hence those who dwell in it are Aes or Fir side, “men of the mound,” or side, fairy folk. The primitive form is probably sedos, from sed, “abode” or “seat”; cf. Greek [Greek: edos] “a temple.” Thurneysen suggests a connection with a word equivalent to Lat. sidus, “constellation,” or “dwelling of the gods.”

[208] Joyce, SH i. 252; O’Curry, MS. Mat. 505.

[209] “Vision of Oengus,” RC iii. 344; IT i. 197 f.

[210] Windisch, Ir. Gram. 118; O’Curry, MC ii. 71; see p. 363, infra.

[211] Windisch, Ir. Gram. 118, Sec. 6; IT iii. 407; RC xvi. 139.

[212] Shore, JAI xx. 9.

[213] Rhys, HL 203 f. Pennocrucium occurs in the Itinerary of Antoninus.

[214] Keating, 434.

[215] Joyce, SH i. 252.

[216] In Scandinavia the dead were called elves, and lived feasting in their barrows or in hills. These became the seat of ancestral cults. The word “elf” also means any divine spirit, later a fairy. “Elf” and side may thus, like the “elf-howe” and the sid or mound, have a parallel history. See Vigfusson-Powell, Corpus Poet. Boreale, i. 413 f.

[217] Tuan MacCairill (LU 166) calls the Tuatha Dea, “dee ocus andee,” and gives the meaning as “poets and husbandmen.” This phrase, with the same meaning, is used in “Coir Anmann” (IT iii. 355), but there we find that it occurred in a pagan formula of blessing—“The blessing of gods and not-gods be on thee.” But the writer goes on to say—“These were their gods, the magicians, and their non-gods, the husbandmen.” This may refer to the position of priest-kings and magicians as gods. Rhys compares Sanskrit deva and adeva (HL 581). Cf. the phrase in a Welsh poem (Skene, i. 313), “Teulu Oeth et Anoeth,” translated by Rhys as “Household of Power and Not-Power” (CFL ii. 620), but the meaning is obscure. See Loth, i. 197.

[218] LL 10b.

[219] Cormac, 4. Stokes (US 12) derives Anu from (p)an, “to nourish”; cf. Lat. panis.

[220] Leicester County Folk-lore, 4. The Coir Anmann says that Anu was worshipped as a goddess of plenty (IT iii. 289).

[221] Rhys, Trans. 3rd Inter. Cong. Hist. of Rel. ii. 213. See Grimm, Teut. Myth. 251 ff., and p. 275, infra.

[222] Rhys, ibid. ii. 213. He finds her name in the place-name Bononia and its derivatives.

[223] Cormac, 23.

[224] Caesar, vi. 17; Holder, s.v.; Stokes, TIG 33.

[225] Girald. Cambr. Top. Hib. ii. 34 f. Vengeance followed upon rash intrusion. For the breath tabu see Frazer, Early Hist. of the Kingship, 224.

[226] Joyce, SH i. 335.

[227] P. 41, supra.

[228] Martin, 119; Campbell, Witchcraft, 248.

[229] Frazer, op. cit. 225.

[230] Joyce, PN i. 195; O’Grady, ii. 198; Wood-Martin, i. 366; see p. 42, supra.

[231] Fitzgerald, RC iv. 190. Aine has no connection with Anu, nor is she a moon-goddess, as is sometimes supposed.

[232] RC iv. 189.

[233] Keating, 318; IT iii. 305; RC xiii. 435.

[234] O’Grady, ii. 197.

[235] RC xii. 109, xxii. 295; Cormac, 87; Stokes, TIG xxxiii.

[236] Holder, i. 341; CIL vii. 1292; Caesar, ii. 23.

[237] LL 11b; Cormac, s.v. Neit; RC iv. 36; Arch. Rev. i. 231; Holder, ii. 714, 738.

[238] Stokes, TIG, LL 11a.

[239] Rhys, HL 43; Stokes, RC xii. 128.

[240] RC xii. 91, 110.

[241] See p. 131.

[242] Petrie, Tara, 147; Stokes, US 175; Meyer, Cath Finntraga, Oxford, 1885, 76 f.; RC xvi. 56, 163, xxi. 396.

[243] CIL vii. 507; Stokes, US 211.

[244] RC i. 41, xii. 84.

[245] RC xxi. 157, 315; Miss Hull, 247. A baobh (a common Gaelic name for “witch”) appears to Oscar and prophesies his death in a Fionn ballad (Campbell, The Fians, 33). In Brittany the “night-washers,” once water-fairies, are now regarded as revenants (Le Braz, i. 52).

[246] Joyce, SH i. 261; Miss Hull, 186; Meyer, Cath Finntraga, 6, 13; IT i. 131, 871.

[247] LL 10a.

[248] LL 10a, 30b, 187c.

[249] RC xxvi. 13; LL 187c.

[250] Cf. the personification of the three strains of Dagda’s harp (Leahy, ii. 205).

[251] See p. 223, infra.

[252] D’Arbois, ii. 372.

[253] RC xii. 77, 83.

[254] LL 11; Atlantis, London, 1858-70, iv. 159.

[255] O’Donovan, Grammar, Dublin, 1845, xlvii.

[256] RC xii. 77.

[257] Lucian, Herakles.

[258] RC xii. 89. The name is found in Gaulish Gobannicnos, and in Welsh Abergavenny.

[259] IT i. 56; Zimmer, Glossae Hibernicae, 1881, 270.

[260] Atlantis, 1860, iii. 389.

[261] RC xii. 89.

[262] LL lla.

[263] RC xii. 93.

[264] Connac, 56, and Coir Anmann (IT iii. 357) divide the name as dia-na-cecht and explain it as “god of the powers.”

[265] RC xii. 67. For similar stories of plants springing from graves, see my Childhood of Fiction, 115.

[266] RC xii, 89, 95.

[267] RC vi. 369; Cormac, 23.

[268] Cormac, 47, 144; IT iii. 355, 357.

[269] IT iii. 355; D’Arbois, i. 202.

[270] LL 246a.

[271] Irish MSS. Series, i. 46; D’Arbois, ii. 276. In a MS. edited by Dr. Stirn, Oengus was Dagda’s son by Elemar’s wife, the amour taking place in her husband’s absence. This incident is a parallel to the birth-stories of Mongan and Arthur, and has also the Fatherless Child theme, since Oengus goes in tears to Mider because he has been taunted with having no father or mother. In the same MS. it is the Dagda who instructs Oengus how to obtain Elemar’s sid. See RC xxvii. 332, xxviii. 330.

[272] LL 245b.

[273] IT iii. 355.

[274] O’Donovan, Battle of Mag-Rath, Dublin, 1842, 50; LL 246a.

[275] D’Arbois, v. 427, 448.

[276] The former is Rhys’s interpretation (HL 201) connecting Cruaich with cruach, “a heap”; the latter is that of D’Arbois (ii. 106), deriving Cruaich from cru, “blood.” The idea of the image being bent or crooked may have been due to the fact that it long stood ready to topple over, as a result of S. Patrick’s miracle. See p. 286, infra.

[277] Vallancey, in Coll. de Rebus Hib. 1786, iv. 495.

[278] LL 213b. D’Arbois thinks Cromm was a Fomorian, the equivalent of Taranis (ii. 62). But he is worshipped by Gaels. Crin, “withered,” probably refers to the idol’s position after S. Patrick’s miracle, no longer upright but bent like an old man. Dr. Hyde, Lit. Hist. of Ireland, 87, with exaggerated patriotism, thinks the sacrificial details are copied by a Christian scribe from the Old Testament, and are no part of the old ritual.

[279] RC xvi. 35, 163.

[280] Fitzgerald, RL iv. 175.

[281] RC xxvi. 19.

[282] Annals of the Four Masters, A.M. 3450.

[283] RC xii. 83, 85; Hyde, op. cit. 288.

[284] LU 94.

[285] RC xii. 65. Elsewhere three supreme “ignorances” are ascribed to Oengus (RL xxvi. 31).

[286] RC iii. 342.

[287] LL 11c; LU 129; IT i. 130. Cf. the glass house, placed between sky and moon, to which Tristan conducts the queen. Bedier, Tristan et Iseut, 252. In a fragmentary version of the story Oengus is Etain’s wooer, but Mider is preferred by her father, and marries her. In the latter half of the story, Oengus does not appear (see p. 363, infra). Mr. Nutt (RC xxvii. 339) suggests that Oengus, not Mider, was the real hero of the story, but that its Christian redactors gave Mider his place in the second part. The fragments are edited by Stirn (ZCP vol. v.).

[288] HL 146.

[289] See my Childhood of Fiction, 114, 153. The tale has some unique features, as it alone among Western Maerchen and saga variants of the “True Bride” describes the malicious woman as the wife of Mider. In other words, the story implies polygamy, rarely found in European folk-tales.

[290] O’Grady, TOS iii.

[291] RC i. 41.

[292] O’Curry, MC i. 71.

[293] LL 117a. See p. 381, infra.

[294] Cumont, RC xxvi. 47; D’Arbois, RC xxvii. 127, notes the difficulty of explaining the change of e to i in the names.

[295] HL 121.

[296] See Crooke, Folk-Lore, viii. 341. Cf. Herod, ii. 131.

[297] Loth, i. 269.

[298] HL 563.

[299] Train, Isle of Man, Douglas, 1845, ii. 118; Grimm, Teut. Myth. ii. ch. 24; Frazer, GB{2} ii. 99 f.

[300] Bathurst, Roman Antiquities at Lydney Park, 1879; Holder, s.v. “Nodons.”

[301] See Rhys, HL 122; Cook, Folk-Lore, xvii. 30.

[302] Stokes, US 194-195; Rhys, HL, 128, IT i. 712.

[303] Loth, ii. 235, 296. See p. 160, infra.

[304] Joyce, OCR.

[305] For these four Manannans see Cormac 114, RC xxiv. 270, IT iii. 357.

[306] O’Grady, ii.

[307] Bodley Dindsenchas, No. 10, RC xii. 105; Joyce, SH i. 259; Otia Merseiana, ii. “Song of the Sea.”

[308] LU 133.

[309] Moore, 6.

[310] Geoffrey, Vita Merlini, 37; Rees, 435. Other saintly legends are derived from myths, e.g. that of S. Barri in his boat meeting S. Scuithne walking on the sea. Scuithne maintains he is walking on a field, and plucks a flower to prove it, while Barri confutes him by pulling a salmon out of the sea. This resembles an episode in the meeting of Bran and Manannan (Stokes, Felire, xxxix.; Nutt-Meyer, i. 39). Saints are often said to assist men just as the gods did. Columcille and Brigit appeared over the hosts of Erin assisting and encouraging them (RC xxiv. 40).

[311] RC xii. 59.

[312] Folk-Lore Journal, v. 66; Rhys, HL 314.

[313] Larminie, “Kian, son of Kontje.”

[314] Joyce, OCR 37.

[315] D’Arbois, vi. 116, Les Celtes, 39, RC xii. 75, 101, 127, xvi. 77. Is the defaced inscription at Geitershof, Deo M … Sam … (Holder, ii. 1335), a dedication to Mercury Samildanach? An echo of Lug’s story is found in the Life of S. Herve, who found a devil in his monastery in the form of a man who said he was a good carpenter, mason, locksmith, etc., but who could not make the sign of the cross. Albert le Grand, Saints de la Bretagne, 49, RC vii. 231.

[316] Holder, s.v.; D’Arbois, Les Celtes, 44, RC vii. 400.

[317] Holder, s.v. “Lugus.”

[318] Stokes, TIG 103. Gaidoz contests the identification of the Lugoves and of Lug with Mercury, and to him the Lugoves are grouped divinities like the Matres (RC vi. 489).

[319] HL 425.

[320] See p. 349, infra.

[321] See p. 272, infra.

[322] HL 409.

[323] See Loth, RC x. 490.

[324] Leahy, i. 138, ii. 50, 52, LU 124b.

[325] LL 215a; see p. 78, supra.

[326] See, further, p. 385, infra.

[327] The Welsh People, 61. Professor Rhys admits that the theory of borrowing “cannot easily be proved.”